Rossetti Archive Textual Transcription

The full Rossetti Archive record for this transcribed document is available.

BROADWAY

ANNUAL

A MISCELLANY OF

ORIGINAL LITERATURE

IN

POETRY AND PROSE.

LONDON AND NEW YORK:

GEORGE ROUTLEDGE AND SONS.

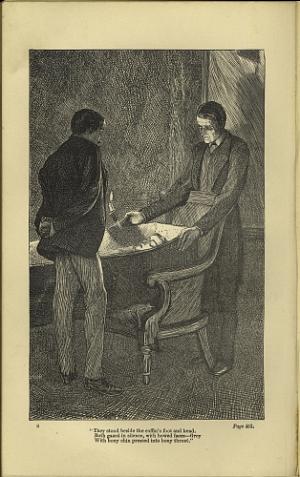

- “They stood beside the coffin's foot and head.

- Both gazed in silence, with bowed faces—Grey

- With bony chin pressed into bony throat.”

- Rain-washed for hours, the streets at last were dried.

- Profuse and pulpy sea-weed on the beach,

- Pushed by the latest heavy tide some way

- Across the jostled shingle, was too far

- For washing back, now that the sea at ebb

- Left an each time retreating track of foam.

- There were the wonted tetchy and sidelong crabs,

- With fishes silvery in distended death.

- No want of blue now in the upper sky:—

- 10But also many piled-up flat grey clouds,

- Threatening a stormy night-time; and the sun

- Sank, a red glare, between two lengthened streaks,

- Hot dun, that stretched to southward; and at whiles

- The wind over the water swept and swept.

- The townspeople, and, more, the visitors,

- Were passing to the sea-beach through the streets,

- To take advantage of the lull of rain.

- The English “Rainy weather” went from mouth

- To mouth, with “Very” answered, or a shrug

- 20Of shoulders, and a growl, and “Sure to be!

- Began the very day that we arrived.”

- “Yes,” answered one who met a travelling friend;

- “I had forgotten that in England you

- Must carry your umbrella every day.

- Au Englishman's a centaur of his sort,

- Man cross-bred with umbrella. All the same,

- I say good-bye to France and Italy,

- Now that I'm here again. Excuse me now,

- As I was going up into the town

- 30To feast my eyes on British tiles and slates.”

- So on he walked, looking about him. Rows

- Of houses were passed by, irregular;

- Many compacted of the shingle-stones,

- Round, grey or white—with each its garden patch

- Now as the outskirts neared; and down the streets

- Which crossed them he was catching glimpses still

- Of waves which whitening shattered out at sea.

- The road grew steep here, climbing up a slope

- Strewn with October leaves, which followed him,

- 40Or drifted edgeways on. The grey advanced,

- Half colour and half dusk, along the sky.

- A dead leaf from a beech-tree loosed itself,

- And touched across his forehead. As he raised

- His eyes, they caught a window, and he stopped—

- An opened upper window of a house

- With close-drawn blinds. A man was settled there,

- Eager in looking out, yet covertly.

- He watched, nor moved his eyes from that he watched.

- The passenger drew close beside the rails,

- 50Looking attentively. “Why, Grey,” he cried;

- “Can that be you, Grey? I had thought you'd been——”

- The face turned sharply on him, and the eyes

- Glanced down, and both hands pulled the window shut.

- Pushing a wicket gate, the other went

- On to the door, expecting it to unclose.

- The garden was but scantly stocked with flowers,

- And these were fading mostly, thinly leaved,

- The earth-plots littered with the fall of them.

- Stately some dahlia-clusters yet delayed,

- 60Crimson, alternating with flame-colour.

- He stretched his fingers to the velvet bloom

- Of one, and drew a petal 'twixt them. Then

- The plaited flower fell separate all to earth

- By ring and ring; only the calyx stood

- Upon its stalk. The autumn time was come.

- Out of the bordering box stiff plantain grew.

- Scarce would the loose trees have afforded shade,

- So lessened was the bulk between their boughs,

- Had there been sun to cast it. In the grass

- 70Rested the moisture of the recent rain.

- No one seemed coming; so he walked some steps

- Backward, and peered: no sign of any one.

- He knocked, and at the touch the door unclosed.

- “Don't you remember, years ago, your friend,

- And correspondent since, John Harling?”

- “Oh,

- I know you, sir, of course—I did at once.”

- “ Sir! Why, how now? Between old friends like us?

- How many letters that begin ‘ Dear John ,’

- In your handwriting, I have asked after,

- 80These eight years, in some scores of postes-restantes!

- Too many, I should hope, for us to Sir

- Each other now. But only tell me, Grey——”

- Grey said, “Come up, come up.”

- There was a haste

- About his words and manner, and he seemed

- To half forget what first he meant to do.

- He paused at the stairs' foot; then, with a glance

- Thrown backward at his friend, who stayed for him,

- He mounted hurriedly, two steps at once.

- They had not shaken hands yet. Harling his

- 90Had proffered with the words he uttered first,

- But Grey had not appeared to notice it.

- Harling had caught the look of the other's face

- Where twilight in the doorway glimmered fresh,

- And he had fancied it was pale and worn,

- And anxious as with watchings through the night.

- But in the room the light no longer served

- For one to see the other, how the weeks

- Had changed him, and the months and years. The room

- Was dim between the window-blinds and dusk.

- 100Now seated—“As you see, John,” Grey began,

- “This is a bed-room. I have not had time

- To trouble myself yet about the house.”

- “You are but just arrived, then?”

- “Yes, but just.”

- He was about to say some more, but stopped.

- “And now,” said Harling, “you shall tell me all

- About yourself. And how and where's your wife?

- What is it brought you down here? Have you left

- Oxford, in which your practice was so good?

- Or are you here on holidays? I come

- 110Upon you by an unexpected chance.

- There must be something to be learned, I know;

- Chances are not all chance-work. Tell me all.”

- His friend rose up at this; and Harling saw

- His knuckles on his forehead, at his hair,

- And thought his eyes grew larger through the dark.

- Grey touched him on the shoulder, drawing breath

- To speak with, but he then again sat down.

- “Why, first I ought to hear your news, I think,”

- At last he answered, swallowing the gasps

- 120Which came into his mouth, and clipped his words.

- “Though travellers have a vested right to lie,

- I'll take it all on trust.” He forged a laugh.

- Harling grew certain there was something now

- His friend had got to tell, and must, but feared.

- He knew how such a fear, by yielding grows,

- And would have had him speak it out at once.

- Nevertheless he answered, “As you will.

- And yet I have but little left to say

- Since my last letter. But the whole is this.

- 130But let us first have light before we talk,

- That we may know each other once again.

- I shall not flatter you if grizzled hairs

- Prove to outnumber your original brown,

- But tell you truth. You tell the truth of me.

- I am more than half a Frenchman, I believe,

- By this time. That's no compliment, say I,

- For a John Bull at heart, and I am one;

- Thank God, a Tory, and hang the Marseillaise!”

- “No lights, no lights,” Grey answered, moodily.

- 140“Can we not talk again as once we used,

- Through twilight and through evening into night,

- Knowing, without a light, it was we two?—

- I little thought then it would come to this,”

- He added, and his voice was only sad.

- “And it is well, too, that the light should come,

- For then perhaps you will have made a guess,

- By seeing me, before I tell it you.

- My dear old friend, it's needless now to attempt

- To hide it. I am wretched—that's the word.

- 150I am a fool not to have got the thing

- Over already, for it has to come

- At last. But there's a minute's respite still,

- For first you were to tell me of yourself;

- So, Harling, you speak now. But first the light.”

- The other, leaning forward, took his hand,

- And tried to speak some comfort; but the words

- Faltered between his lips. For he was sure

- That, if he had already heard this grief,

- He would not talk of comfort, but sit dumb.

- 160The lights were come now, and each looked on each.

- The traveller's face was bronzed, and his hair crisp

- And close, and his eyes steady—all himself

- Compact and prompt to any chance. And yet

- He was essentially the same who went,

- To find his level, forth eight years ago,

- Unformed, florid-complexioned, easy-tongued:

- Travel and time had only mellowed him.

- Grey was the same in feature, not in fact.

- His face was paler that was always pale;

- 170The forehead something wrinkled, and the lips

- Arid and meagre, faded, marked with lines;

- The eyes had sunken further in the head,

- With a dark ridge to each, and grizzled brows;

- His hair, though as of old, was brown and soft.

- The difference was less, but more the change.

- Each looked on each some minutes: neither spoke.

- His friend was clothed in black, as Harling saw,

- Who now resumed the thread of his discourse.

- “As for my own adventures, they are few:

- 180For, after I left Rome—the storm will burst,

- Be sure, at Rome, before the year is done—

- I went straight back to Paris. Politics,

- You know, I've stood aloof from all the year;

- But even with me, too, they have done their work.

- My poor Louise was dead—shot down, I learned,

- Upon the people's barricades in June:

- She turned up quite a Red Republican

- After their twenty-fourth of February;

- And my successor in her graces fell

- 190With her—both fighting and yelling side by side.

- I could not but curse at them through my teeth

- With her own sacré-Dieu's—the whole of them

- Who get up revolutions and revolts.

- And then they swore I was an Orleanist,

- An English spy, or something; and indeed

- I found myself, the scanty days I stopped,

- A centre-piece for all the blackest looks.

- At least I thought so. Many of my friends,

- Besides, were gone, waiting for better times

- 200When next they come to Paris. So I left

- Disgusted, and crossed over. Why should I

- Quit England and dear brother Tories? still,

- Although I do now think of settling here,

- Perhaps, before another twelvemonth goes,

- The South will tempt me back—sooner, perhaps.

- I must, I think, die travelling in the South.”

- He made an end of speaking. Grey looked up.

- “Is there no more?” he asked. He said, “No more.”

- Grey's face turned whiter, and his fingers twitched.

- 210“It is my turn to speak, then”:—and he rose,

- Taking a candle: “come this way with me.”

- They stepped aside into a neighbouring room.

- Grey walked with quiet footsteps, and he turned

- So noiselessly the handle of the door

- That Harling fancied some one lay asleep

- Inside. The hand recovered steadiness.

- The room was quite unfurnished, striking chill.

- A rent in the drawn window-blind betrayed

- A sky unvaried, moonless, cloudless, black.

- 220Only two chairs were set against the wall,

- And, not yet closed, a coffin placed on them.

- Harling's raised eyes inquired why he was brought

- Hither, and should he still advance and look.

- “It is my wife,” said Grey; “look in her face.”

- This in a whisper, holding Harling's arm,

- And tightened fingers clenched the whispering.

- Harling could feel his forehead growing moist,

- And sought in vain his friend's averted eyes.

- Their steps, suppressed, creaked on the uncovered boards:

- 230They stood beside the coffin's foot and head.

- Both gazed in silence, with bowed faces—Grey

- With bony chin pressed into bony throat.

- The woman's limbs were straight inside her shroud.

- The death which brooded glazed upon her eyes

- Was hidden underneath the shapely lids;

- But the mouth kept its anguish. Combed and rich

- The hair, which caught the light within its strings,

- Golden about the temples, and as fine

- And soft as any silk-web; and the brows

- 240A perfect arch, the forehead undisturbed;

- But the mouth kept its anguish, and the lips,

- Closed after death, seemed half in act to speak.

- Covered the hands and feet; the head was laid

- Upon a prayer-book, open at the rite

- Of solemnizing holy matrimony.

- Her marriage-ring was stitched into the page.

- Grey stood a long while gazing. Then he set

- The candle on the ground, and on his knees

- Close to her unringed shrouded hand, he prayed,

- 250Silent. With eyes still dry, he rose unchanged.

- They left the room again with heeded steps.

- On friendly Harling lay the awe of death

- And pity: he took his seat without a sound.

- Some of the hackneyed phrases almost passed

- His lips, but shamed him, and he held his peace.

- “Harling,” said Grey, after a pause, “you think

- No doubt that this is all—her death is all.

- Harling, when first I saw you in the street,

- I feared you meant to come and speak to me;

- 260So hid myself and waited till you knocked;

- Waited behind the door until you knocked,

- Longing that you, perhaps, would go. When I

- Had opened it, I think I called you Sir—

- Did you not chide me? Do you know, it seemed

- So strange to me that any one I knew

- Before this happened should be here the same,

- And know me for the same that once I was,

- I could not quite imagine we were friends.

- It is not merely death would make one feel

- 270Like this—no, there is something more behind

- Harder than death, more cruel. Let me wait

- Some moments; then no help but I must tell.”

- He gathered up his face into his hands

- From chin to temples, only just to think

- And not be seen. He had not seated him,

- But leaned against the chair. Nor Harling spoke.

- “Two months are gone now,” Grey pursued. “We two

- Lived lovingly. I had to come down here,

- And here I met a surgeon of the town.

- 280Hell only knows—I cannot tell you—why,

- I asked him to return with me, and spend

- A fortnight at our house. Perhaps I wrote

- The whole of this to you when it occurred.

- His name is Luton.”

- Here he chose to pause.

- “Perhaps: I am not certain,” Harling said.

- “I think you might be certain,” answered Grey,

- “If you're my friend.” But then he checked himself,

- Adding: “Forgive me. I am not, you see,

- Myself to-night—this night, nor many nights,

- 290Nor many nights to come. Well, he agreed.

- Of course, he must agree; else I should not

- Have been like this, disgraced, made almost mad.”

- At this he found his passion would be near

- To drive him to talk wildly: so he kept

- Silence again some moments—then resumed.

- “How should I recollect the days we passed

- Together? There must surely have been enough

- To see, and yet I never saw it once.

- Besides, my patients kept me out all day

- 300Sometimes. It was in August, John, was this—

- The end of August, reaping just begun.

- We've had a splendid harvest, you'll have heard.”

- “Indeed!” the other said, shifting the while

- His posture—and he knew not what to say.

- “Yes, you detect me,” Grey cried bitterly;

- “You know I am afraid of what's to come—

- A coward. Now I do hope I shall speak,

- And tell you all of it without a stop.

- There was a lady staying with us then,

- 310A cousin of my wife's—but older, much;

- So that you understand how I could ask

- This Luton down. Before his time was up,

- He seemed to grow uneasy, and he left,—

- Merely explaining, business called him home.

- I said I had not noticed anything

- Unusual; and yet I sometimes found

- Mary in tears, and could not gather why.

- One day she told me when I questioned her

- It was for thinking of our girl that died

- 320Months back—for that her cousin would begin

- Often to talk to her about her own;

- So that would make her sad. I thought it strange

- She had not so informed me from the first.

- Her cousin, when I named the point, appeared

- Surprised; but then to recollect herself,

- And answered—I could see, a little piqued—

- She should not cry again because of her.

- “These fits of tears continued. We were now

- Alone together, for the cousin went

- 330Away soon after. Then I could not help

- Seeing her health and strength were giving way:

- Her mind, too, seemed oppressed. She'd hardly leave

- At nights the chair she sat in, for she said

- ‘This is the only place where I can sleep.’

- Yet her affection for me seemed to grow

- A kind of pity for its tenderness.

- Oh! what is now become of her, that I,

- After to-morrow, shall not see her more,

- But have to hide her always from my sight?”

- 340He took some steps, meaning to go again

- And see her corpse; but, meeting Harling's eye,

- Turned and sat down.

- “Is it not,” he pursued,

- With floorward gaze, “hard on me I must tell

- This business word by word, the whole of it,

- While I can see it all before me there,

- And it is clear one word could tell it all?

- Can you not guess the rest, and spare me now?”

- “I will not guess; but you,” said Harling, “keep

- All that remains unspoken; for it wrings

- 350My heart, dear Grey, dear friend, to see you thus.”

- “No, it is better I should speak it out,

- For you would fancy something; and at least

- You will not need to fancy when you know.

- She came to me one morning—(this was like

- A fortnight after he had gone away,

- This Luton)—saying that she found it vain

- Attempting to compose her mind at home;

- That every place made her remember what

- The baby had done or looked there, and she felt

- 360Too weak for that, and meant to see her friends

- (That is, two sisters some few miles from here).

- She spoke more firmly than I had heard her talk

- A long time past—because I thought it long—

- And I believed she had determined right,

- And so consented. But she only said

- ‘I have made up my mind’—thus waiving all

- Consent on my part—mere sick wilfulness

- I took it for. She left the house. I might

- Have told you she'd a lilac dress, and hair

- 370Worn plain. And so I saw her the last time—

- The last time, God in heaven!” He seized his fists

- Together, and he clutched them toward his throat.

- “Many days passed. She had begged me, feeling sure

- It would excite her, not to write a line,

- And said she would not write, nor let her friends.

- I think I did not tell you, though, how pale

- Her cheeks were; and, in saying this, she sobbed,

- For such a lengthened silence looked like death.

- “Three weeks, or nearly that, had passed away:

- 380A letter on black-bordered paper came.

- It was from Luton. Then I did not know

- The hand, but shall now, if it comes again.

- He wrote that I must go immediately,

- That I was ‘to prepare myself’—some trash:

- He ‘dared not trust his pen to tell me more.’

- “On Thursday I arrived here. I cannot

- Attempt to tell you all about it. When

- You've read this, only call me, and I'll come;

- But I will not be by you while you read.

- 390On the first day I heard it all from him,

- And loathe him for it. I am left alone,

- And all through him.”

- He took a newspaper

- From underneath his pillow, and he showed

- The place to read at. Then he left the room;

- And Harling caught his footfall toward the corpse,

- And touching of his knees upon the boards.

- And this is what he feverishly perused:—

- “ Coroner's Inquest—A Distressing Case .

- An inquest was held yesterday, before

- 400The County Coroner, into the cause

- Of the decease of Mrs. Mary Grey,

- A married lady. Public interest

- Was widely excited.

- “When the Jury came

- From viewing the corpse, in which are seen remains

- Of no small beauty, witnesses were called.

- “Mr. Holmes Grey, surgeon, deposed: ‘I live

- In Oxford, where I practise, and deceased

- Had been my wife for upwards of three years.

- About the middle of September, she

- 410Was suffering much from weakness, and a weight

- Seemed on her mind. The symptoms had begun

- Nearly a month before, and still increased,

- Until at last they gave me great alarm,

- Of which we often spoke. On the eighteenth

- She told me she would like to stay awhile

- With two of her sisters, living on the coast,

- At Barksedge House, not far from here. She went

- Next day. I cannot speak to any more.’

- “The Coroner: ‘How were you first apprised

- 420Of this most melancholy event?’—‘By note

- Addressed to me by Mr. Luton here.’

- “A Juror: ‘Could your scientific skill

- Assign some cause for this debility?’

- ‘No. I believed it was occasioned (so

- She intimated) by a domestic grief

- Quite unconnected with the present case.’

- “The Coroner: ‘You'll know how to excuse

- The question which I feel compelled to put:

- I have a public duty to perform.

- 430Had you, before the period you described,

- Any suspicions ever?’—‘Never once:

- There was no cause for any, I swear to God.’

- “The witness had, throughout his testimony,

- Preserved his calm—though clearly not without

- An effort, which augmented towards the close.

- “Jane Langley: ‘I keep lodgings in the town.

- On the nineteenth September the deceased

- Engaged a bed-room and a sitting-room.

- The name I knew her by was Mrs. Grange.

- 440I saw but very little of her; she kept,

- As much as that well could be, to herself,

- And she would frequently leave home for hours.

- I cannot say I made any remark

- Especially. I found a letter once—

- Just a few words, torn up. ‘Holmes,’ it began.

- ‘This letter is the last you ever will . . .’

- No more, I think. I threw the bits away.

- That was, perhaps, four days before her death.

- On that day, I suppose, as usual,

- 450She left the house: I did not see her, though.

- She was brought home quite dead.’

- “Upon the name

- Of the next witness being called, some stir

- Arose through persons pressing on to look.

- After it had been silenced, and the oath

- Duly administered, the evidence

- Proceeded.

- “Mr. Edward Luton, surgeon:

- ‘I lately here began for the first time

- In my profession. I was introduced

- To Mr. Grey in August. When he left

- 460The seaside, he invited me to pass

- A fortnight at his house, and I agreed.

- On seeing Mrs. Grey, I recognized

- In her a lady I had known before

- Her marriage, a Miss Chalsted. We had met

- In company, and, in particular,

- At some so-called “mesmeric evenings,” held

- At her remote connection's house, the late

- Dr. Duplatt. But now, as Mrs. Grey

- Allowed my presentation to pass off

- 470Without a hint of knowing me, I left

- This point to her, and seemed a stranger: till

- We chanced, the sixth day, to be left alone.

- I talked on just the same, but she was silent.

- At last she answered, and began to speak

- Familiarly of when she knew me first;

- Without explaining—merely as one might talk

- Changing the subject. But I let it pass.

- And yet, when we were next in company,

- Once more she acted new acquaintanceship.

- 480Then, two days after, I believe—one time

- Her cousin, Mrs. Gwyllt, was out by chance—

- The same thing happened; but she spoke of love

- Now, and the very word half passed her lips.

- Our talk ended abruptly. Mrs. Gwyllt

- Came in, and by her face I saw she had heard.

- “‘This instance was the last we talked alone.

- And I began to hear from Mr. Grey

- His wife was far from well, and had the tears

- Now often in her eyes. This made me feel

- 490Hampered and restless: so I took my leave

- After my first eleven days' stay was gone,

- Saying I had affairs that could not wait.

- “‘Between the seventh of September, when

- We parted, and the twenty-third, I saw

- No more of the deceased. Towards seven o'clock

- That evening, I was told a lady wished

- To speak with me. She entered: it was she—

- Deceased. I can't describe how pained I was

- At finding she had left her home like this.

- 500She said she loved me, and conjured me much

- Not to desert her; that that she loved me young;

- That, after we had ceased to meet, she knew

- And married Mr. Grey. Also, that when

- He wrote to her in August I should come,

- Guessing who I must be, she thought it well

- To treat me as a stranger—dreading lest

- Her love (so she assured me) should revive.

- All this through sobs and blushes. I could not

- Make up my mind what conduct to pursue:

- 510I begged her to be calm, and wait awhile,

- And I would write. She left unnerved and weak.

- “‘I took five days, bewildered how to act.

- But on the evening of the fifth, I saw,

- While looking out of window—(it was dusk,

- And almost nightfall)—Mrs. Grey, who paced,

- Muffled in clothes, before my door. I knew

- By this how dangerous it must be to wait

- For a day longer; so I wrote at once

- She absolutely must return to her home.

- 520Nothing was known as yet—all might be well;

- In time she would forget me; and besides

- I was engaged to marry, and must regard

- Our intercourse as ended.

- “‘She returned

- Next day, the twenty-ninth; and, falling down

- Upon her knees, she cried, with hardly a word,

- Some while, and kept her face between her hands;

- But at the last she swore she would not go,

- But rather die here. It continued thus

- Six days. For she would come and seat herself,

- 530When I was present, in my room, and sit,

- An hour or near, quite silent; or break out

- Into a flood of words—and then, perhaps

- Between two syllables, stop short, and turn

- Round in her chair, and sob, and hide her tears.

- “‘The sixth day, after she had left the house,

- I had an intimation we were watched,

- And certain persons had begun to talk.

- I thought it indispensable to write

- Once more, and tell her the could not remain—

- 540I owed it to myself not to allow

- This state of things to last; that I had given

- The servant orders to deny me, should

- She still persist in calling.

- “‘Towards mid-day

- Of the sixth instant, the deceased once more

- Was at my house, however;—darted through

- The door, which happened to be left ajar,

- And flung herself right down before my feet.

- This day she did not shed a single tear,

- Nor talk at all at random, but was firm:

- 550I mean, unalterably resolute

- In purpose, and her passion more uncurbed

- Than ever: swore it was impossible

- She should return to live with Mr. Grey

- Again; that, were she at her latest hour,

- She still would say so, and die saying so:

- ‘Because’ (I recollect her words) ‘this flame

- All eats me up while I am here with you;

- I hate it, but it eats me—eats me up,

- Till I have now no will to wish it quenched.’

- 560I hope to be excused repeating all

- That I remember to have heard her say.

- She bitterly upbraided me for what

- I last had written to her, and declared

- She hated me and loved me all at once

- With perfect hate as well as burning love.

- This must have lasted fully half an hour.

- However fearful as to the results,

- I told her simply I could not retract,

- And she must go, or I immediately

- 570Would write to Mr. Grey. I rose at this

- To leave the room.

- “‘She staggered up as well,

- And screamed, and caught about her with her hands:

- I think she could not see. I dreaded lest

- She might be falling, and I held her arm,

- Trying to guide her out. As I did so,

- She, in a hurry, faced on me, and screamed

- Aloud once more, and wanted, as I thought,

- To speak, but, in a second, fell.

- “‘I raised

- Her body in my arms, and found her dead.

- 580I had her carried home without delay,

- And a physician called, whose view concurred

- With mine—that instant death must have ensued

- Upon the rupture of a blood-vessel.’

- “This deposition had been listened to

- In the most perfect silence. At its close

- We understand a lady was removed

- Fainting.

- “The Coroner: ‘You said just now

- That, in your former letter to deceased,

- You told her nothing yet was known. Was not

- 590Her absence traced, then, and suspicion roused?

- Did she inform you?’ ‘She informed me that

- Would not be, for that Mr. Grey and she

- Had mutually consented not to write.

- I have forgotten why.’

- “The Coroner:

- ‘Is Mr. Grey still present?’ Mr. Grey:

- ‘Yes, I am here.’ ‘You heard the last reply;

- Was such the case?’ ‘It was; we had agreed

- To exchange no letters, that her mind might have

- The benefit of more complete repose.’

- 600“A Juror to the witness: ‘Did no acts

- Of familiarity occur between

- Deceased and you?’

- “Here Mr. Grey addressed

- The Coroner, demurring to a reply.

- “The Coroner: ‘It grieves me very much

- To pain your feelings; but I feel compelled

- To say the question is a proper one.

- It is the Jury's duty to gain light

- On this exceedingly distressing case;

- The public mind has to be satisfied;

- 610I owe a duty to the public. Let

- The witness answer.’

- “Witness: ‘She would clasp

- Her arms around me in speaking tenderly,

- And kiss me. She has often kissed my hands.

- Not beyond that.’

- “The Juror: ‘And did you

- Respond——’ The Coroner: ‘The witness should,

- I think, be pressed no further. He has given

- His painful evidence most creditably.’

- “The Juror: ‘Did deceased, in all these days,

- Not write to you at all?’ ‘She sent me this:

- 620It is the only letter I received.’

- “A letter here was handed in and read.

- It ran as follows, and it bore the date

- Of twenty-sixth September.

- “‘Dearest Friend,—

- Where is your promise you would write me soon

- My sentence, death or life? This is the third

- Of three long days since last I saw you. Oh!

- To press your hand again, and talk to you,

- And see the moving of your lips and eyes!

- Edward, I'm certain that you cannot know

- 630How much I love you; you must not decide

- Until convinced of it—— But words are dead.

- That, Edward, is a love in very truth

- Which can avail to overcome such shame

- As kept me four whole days from seeing you—

- Four days after my coming quite resolved

- To strive no more, but tell you all my heart.

- As daylight passed, and night devoured the dusk,

- The first time, and the second, and the third,

- I doubted whether I could ever wait

- 640Till dawn—yet waited all the fourth day too,

- Staring upon my hands, and looking strange;

- Yes, and the fifth day's twilight hastened on.

- But love began then driving me about

- Between my house and your house, to and fro.

- At last I could no more delay, but wept,

- And prayed of Christ (for He discerns it all),

- That, if this thing were sinful unto death,

- He would Himself be first to throw the stone.

- So then I came and saw you, and I spoke.

- 650Did I not make you understand how I

- Had loved you in the budding of my youth;

- And how, when we divided, all my hope

- Went out from me for all the future days,

- And how I married, just indifferent

- To whom I took? Perhaps I did not clear

- This up enough, or cried and troubled you.

- Why did I ever see your face again?

- I had forgotten you; I lived content,

- At peace. Forgotten you! that now appears

- 660Impossible, yet I believe I had.

- Then see what now my life must be—consumed

- With inner very fire, merely to think

- Of you, and having lost my heartless peace.

- How shall I dare to live except with you?’

- “The Coroner to Witness: ‘Had you known

- When you were first acquainted with deceased,

- Before her marriage, that she entertained

- These feelings for you?’—‘Friends of mine would talk

- In a light way about it—nothing more—

- 670And in especial as to mesmerism.

- I knew that such a match could never be;

- Her friends would have been sure to break it off—

- Our prospects were so very different.

- I did not think about it seriously.’

- “‘The letter says that you divided: how

- Did that occur?’—‘I left the neighbourhood

- On account solely of my own affairs.’

- “‘You have deposed that you received a hint

- Your meetings with deceased had been observed.

- 680How did you learn this?’—‘Through the brother-in-law

- Of a young lady that's engaged to me.’

- “The witness here retired. He looks about

- The age of twenty-seven,—in person, tall

- And elegant. His tone at times betrayed

- Much feeling.

- “Mrs. Celia Frances Gwyllt:

- ‘Deceased and I were cousins. In the month

- Of August last I spent a little time

- With her and Mr. Grey. In the first week

- Of last month, I remember hearing her

- 690Speak in a manner I considered wrong

- To Mr. Luton, and she seemed confused

- When she perceived me. Shortly afterwards,

- I took occasion to inform her so.

- This she at first made light of, and alleged

- It was a mere flirtation. I replied,

- I deemed it was my duty to acquaint

- Her husband; when she begged that I would not,

- So that at length I yielded. Then came on

- Some crying fits, which Mr. Grey was led

- 700To ascribe to things I chanced to talk about.

- This and my pledge of silence vexed me much,

- And so, soon after that, I took my leave.’

- “Anne Gorman: ‘I am Mr. Luton's servant.

- On Tuesday was the sixth I had to go

- Out on an errand, with the door ajar,

- When I remembered something I had left

- Behind. On coming back, I saw deceased

- Race through the lobby, and whisk into the room.

- I had been ordered not to let her in.’

- 710“The evidence of Dr. Wallinger

- Ended the case. ‘I was called in to see

- The body of deceased upon the sixth:

- Life then was quite extinct; the cause of death,

- Congestion and effusion of the ventricle.

- Death would be instantaneous. Any strong

- Emotion might have led to that result.’

- “The Coroner, in course of summing up,

- Commented on the evidence, and spoke

- Of deceased's conduct in appropriate terms;

- 720Observing that the Jury would decide

- Upon their verdict from the testimony

- Of the professional witness—which was clear,

- And seemed to him conclusive. He could do

- No less than note the awful suddenness

- With which the loss of life had followed such

- A glaring sacrifice of duty's claims.

- “The Jury gave their verdict in at once:

- ‘Died by the visitation of God.’

- “We learn

- On good authority that the deceased

- 730Belonged to a distinguished family.

- Her husband's scientific eminence

- Is fully and most widely recognized.”

- As Harling finished reading this, he rose

- To call his friend; but, shrinking at the thought,

- He read it all again and lingeringly.

- But, after that, he called in undertone;

- And he received the answer, “Come in here.”

- He entered therefore.

- Grey was huddled o'er

- The coffin, looking hard into her face.

- 740“You know it now,” he said, but did not move.

- “We long have been old friends,” Harling replied.

- “Words are of no avail, and worse than none.

- I need not try to tell you what I feel.”

- Grey now stood straight. “I am to bury her

- The day after to-morrow: I alone

- Shall see her covered in beneath the earth.

- May God be near her in the stead of men,

- And let her rest. Yet there is with her that

- Which she shall carry down into the grave;

- 750Still in the dark her broken marriage-vow

- Under her head: they shall remain together.

- How can I talk like this?” And he broke off.

- “This is a crushing grief indeed, I know,”

- Said Harling; “yet be brave against it. When

- This few days' work is over, Grey, go home,

- And mind to be so occupied as must

- Prevent your dwelling on it. If you choose,

- I will accompany and stay with you.”

- But he replied: “My home will now be here;”

- 760And all the angles of his visage thinned.

- “ He is here I mean to ruin. Shall he still

- Be free to laugh me in his sleeve to scorn,

- And show me pity—pity!—when we meet?

- I have no means of harming him, you think?

- There's such a thing, though, as professional fame,—

- I have it. Where's the name of Luton known?

- [Th]is is my home: I mean to ruin him.”

- “Why, he,” objected Harling, “never did

- One hair's-breadth wrong to you: his hands are clean

- 770Of all offence to you and yours. For shame!

- It was as blind anguish spoke there—not yourself.”

- “Ah! you can talk like that! But it is I

- Who have to feel—I who can see his house

- From here, and sometimes watch him out and in,

- And think she used to be with him inside.

- And he could bear her coming day by day,

- And see the sobs collecting in her throat,

- And tresses out of order, as she fell

- Before his feet, and made her prayers, and wept!

- 780He bore this! What a heart he must have had!

- Must I be grateful for it? Did he not

- Admit inopportune eyes were watching him?

- He was engaged to marry—yes, and one

- For whom he's bound to keep himself in check,

- And crouch beneath her whims and jealousy:—

- Not that I ever saw her, but I'm sure.

- Besides, he told me she would not be his

- Unless he gains the standing deemed her due,—

- And I'll take care of that.”

- His friend was loath,

- 790Seeing the burden of his agony,

- To harass him with argument and blame;

- Yet would he not be by to hear him rave,

- And said he now must go.

- “One moment more,”

- Said Grey, and oped the window. Overhead

- The sky was a black veil drawn close as death;

- The lamps gave all the light, prolonged in rows:

- And chill it blew upon them as they gazed,

- Mixed with thin drops of rain, which might not fall

- Straight downward, but kept veering in the wind.

- 800There was a sounding of the sea from far.

- Grey pointed. “That beyond there is the house,

- Turning the street—that where a candle burns

- In the left casement of the upper three.

- That is, no doubt, his shadow on the blind.

- Often I get a glimpse of it from here,

- As when you saw me first this afternoon.

- Shall he not one day pay me down in full?

- John, I can wait; but when the moment comes . . .!”

- He shut the sash. Harling had seen the night,

- 810Equal, unknown, and desolate of stars.

* The reader will observe the already remote date at which this poem was written. Those were the days when the præ-Raphaelite movement in painting was first started. I, who was as much mixed up and interested in it as any person not practically an artist could well be, entertained the idea that the like principles might be carried out in poetry; and that it would be possible, without losing the poetical, dramatic, or even tragic tone and impression, to approach nearer to the actualities of dialogue and narration than had ever yet been done. With an unpractised hand I tried the experiment; and the result is this blank-verse tale, which is now published, not indeed without some revision, but without the least alteration in its general character and point of view.—W. M. R.

![Image of page [ii]](http://www.rossettiarchive.org/img/thumbs_small/ap4.b9.1.frontispiece.jpg)

![Image of page [iii]](http://www.rossettiarchive.org/img/thumbs_small/ap4.b9.1.titlepage.jpg)

![Image of page [448]](http://www.rossettiarchive.org/img/thumbs_small/ap4.b9.1.facing449.jpg)