Manuscript Addition: (1907) 1s[t] edn. £48

Editorial Note (page ornament): Scroll-patterned box ornament; imprint of the Modern Master Draughtsmen

series

DRAWINGS OF D. G. ROSSETTI

Note: Heavy brown laid paper

Note: Heavy brown laid paper with drawing loosely attached

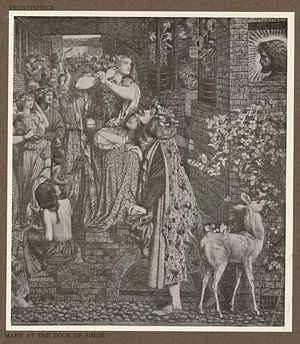

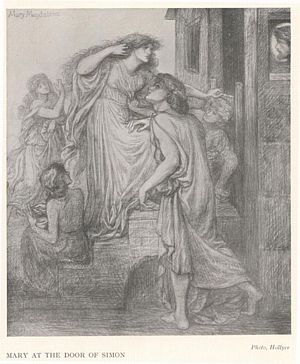

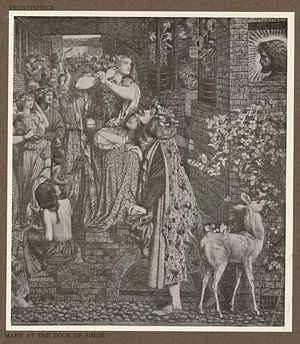

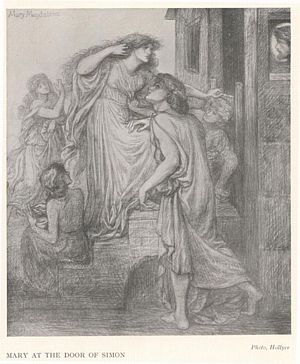

MARY AT THE DOOR OF SIMON

Photo, Mansell

Figure: ‘The scene represents two houses opposite each other, one of which is that

of Simon the Pharisee, where Christ and Simon, with other guests, are seated at table. In

the opposite house a great banquet is held, and feasters are trooping to it dressed in

cloth of gold and crowned with flowers. The musicians play at the door, and each couple

kiss as they enter. Mary Magdalene . . . has been in this procession, but has suddenly

turned aside at the sight of Christ, and is pressing forward up the steps of Simon's house,

and casting the roses from her hair. Her lover and a woman have followed her out of the

procession and are laughingly trying to turn her back. The woman bars the door with her

arm. Those nearest the Magdalene in the group of feasters have stopped short in wonder and

are looking after her, while a beggar girl offers them flowers from her basket. A girl near

the front of the procession has caught sight of Mary and waves her garland to turn her

back. Beyond this the narrow street abuts on the high road and river. The young girl seated

on the steps is a little beggar who has had food given her from within the house, and is

wondering to see Mary go in there, knowing her as a famous woman in the city. Simon looks

disdainfully at her, and the servant who is setting a dish on the table smiles, knowing her

too. Christ looks toward her from within, waiting till she shall reach him. A fawn crops

the vine on the wall where Christ is seen, and some fowls gather to share the beggar girl's

dinner, giving a kind of equivalent to Christ's words: “Yet the dogs under the

table eat of the children's crumbs.” ’Description taken from a letter [from DGR] to Mrs. Clabburn referring to the

unfinished oil replica, July 1865. (

Pall Mall Budget, 22 Jan 1891, p.

14.)qtd. in Surtees, p. 62

Editorial Note (page ornament): Woman painting, accompanied by cherub.

DRAWINGS OF

ROSSETTI

LONDON. GEORGE NEWNES LIMITED

SOUTHAMPTON STREET STRAND

W.C.

NEW YORK. CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

BALLANTYNE PRESS.

LONDON &

EDINBURGH

Editorial Note (page ornament): Text begins with a decorated, boxed capital "T."

BY T. MARTIN WOOD

THE intensely subjective nature of Rossetti's art is what gives it

fascination for its lovers; it belonged to himself. Even in his early period and with his

dramatic subjects this was so, and partly by the depth of imaginative meaning he read into the

faces of women. The last phase of his art was entirely one of self-revelation; his own moments

of sorrow were mirrored in one woman's face, moments in which he created sadly, living over

again in them some hours that had been happy.

- This is her picture as she was :

- It seems a thing to wonder on,

- As though mine image in the glass

- Should tarry when myself am gone.

- for so

- Was the still movement of her hands

- And such the pure line's gracious flow.

- 'Tis she: though of herself, alas!

- Less than her shadow on the grass

-

10Or than her image in the stream.

One might hazard the question whether it were possible for a painter such as Rossetti,

seeking expression in his art for this intensity of feeling, to vie in the rendering of the

external aspects with those painters who have approached life with that cold acuteness to the

appearance of things and aloofness from their meaning characteristic of work that has

contributed largely to the actual science of painting. To Rossetti life came over-crowded,

over-coloured. There was too much for him to realise in his working moments. The very richness

of his nature embarrassed his output. His gifts gave him so many ways of self-expression from

which to choose. The phases through which his genius passed, the result of an inherited and

rare temperament and its adventures, made the science of painting prosaic for him. He himself

felt latterly

that this impatience had left his ideas pathetically at the mercy of

his materials. Apart from the quality in colour to which he attained, one is conscious always

in his paintings of the tragedy of genius striving for expression through an ineffectual

technique. Rossetti's individuality, however, was so strong that it stamped itself everywhere ;

in spite of every limitation his art explains his attitude towards life. In his ability to make

it show this his greatness lies, and in the fact that the point of view that it suggested was

his alone. His art created for itself its own atmosphere—an unfamiliar one at first

to Englishmen, with its subserviency of everything to a romantic emotionalism. The histories of

the world for Rossetti were its stories of emotion, and in every place that his memory knew

Love's image had been set to reign, Love who had wandered down through the ages decked with the

flowers of art, offerings of bygone lovers, dead lovers to never dying Love. As a strange

spirit Rossetti entered modern London. A heart rich from many forgotten experiences seemed to

have lodged itself in him and he painted with eyes filled with the colours of old things. For

him the tapestries could never fade in a room that had known love's history, nor the colours

leave the missal which told the story of a soul.

How far his drawings were intended to foreshadow large paintings which he desired to make as

windows for us to look with him into his romantic country we cannot say. As it is they show

that it was in Rossetti's power to be the greatest imaginative illustrator of his century; that

he was not so seems to prove that in this way, as in some others, he failed to attain to much

that at first had seemed included in his destiny. In his paintings, in his poetry, in these

drawings something there is that was new, and that brought a fresh phase into art and

literature in England. It is something which has influenced permanently the nation's thought

and has been even admitted into the procession of its fashions. For a time women tried to look

as the women in his paintings, so much had the type he chose, which was his own creation,

imposed itself upon their imagination.

The Rossetti woman, if she did not supersede the early Victorian type, at least helped to

change it, and to mark a change which was taking place in the ideals of the nation. Fresh

tendencies in national thought are always correspondingly represented by a change in the type

of women idealised in its art and poetry. When the Victorian type went, the time had passed

when homage was given to women for a surrender of their claims on life. The new type spoke of

the ardent way in which another generation of women was creating for itself wide interests in

the world.

Rossetti displayed in his art the dramatic sense ; we find him in his earlier drawings always

illustrating dramatic subjects, rendering action in his figures in a way that proclaims him at

once as one of those to whom the actions of men, the faces of women, come tragically or

otherwise into every dream. One is enabled to write more clearly on this point by comparing him

with his friend Burne-Jones. Burne-Jones' figures live in a dream in which the world has little

part, whilst Rossetti's dream is of the world itself. His work is rich with the human

experience that is absent in the art of his friend. He is accredited with being the leader of a

phase of decadence, while, as a matter of fact, no one could have heen further removed from

anything like a “decadent” pose. Rossetti had an unconscious and

unexplained sympathy for life that tragically pursued, and found itself shipwrecked upon, its

own illusions. It was part of his art's vitality. There was little defiance in his attitude, it

was altogether one of pity. Indiscriminate publication has familiarised the public only with

the last sad phase of Rossetti's art, and unhappily this is esteemed characteristic. The

intimate patrons of the painter possessed themselves of his early work ; now it is

inaccessible, and it is not at his best that he is seen in any public collection.

It is possible to like the art of Rossetti very deeply, and also to love the changing colours

of the sea and the shadows of the sun clouds moving swiftly on the hills. But often to pagan

lovers of such things the art of Rossetti, shuttered close in its mediæval darkened

rooms, has seemed as an almost poisonous flower, with its forgetfulness of the world without.

It can never be sufficiently emphasised how necessary it is in judging any art first of all

to share some of the mood in which it was created. Those who would enter into the atmosphere of

Rossetti's art must find their way to it in the darkened light of dreams. It stands in no

relation whatever to the workaday world.

A poet whose writings realised an opposite temperament to Rossetti's own would have had the

test of poetry that it could be taken to the fields in the early morning and read. To attempt

to bring a painting of Rossetti's into relationship with nature out of doors would to all

intents put an end to the reason for its artistic existence. It would be to demand of it that

it should strike a note in tune with a mood the direct opposite to that which it was its

intention to create. Though art should always be examined in its own atmosphere, much of the

criticism applied to Rossetti is but the bringing of his art out into the fields. It

is not valuable criticism that approaches work in a spirit of this

kind.

A great deal too much has been made in writing of Rossetti's Pre-Raphaelitism. To a nature

like Rossetti's any school, any methods he may have taken up with, or inspired, would be

largely accidental to his environment. Arrived at a time of reaction, of revolution in English

painting, with his qualities of leadership he threw himself into Pre-Raphaelitism as a new

movement, but it is more than probable his genius would have found methods of expression as

personal to itself in the refinements that entered English painting in the wake of

pre-Raphaelitism,—only the Pre-Raphaelite movement could not have been but for the

ardent genius of Rossetti which poured inspiration into all those who gathered about him. He

departed from Pre-Raphaelite tenets just when it suited him; its hold over him lay chiefly in

that he liked to realise very definitely the shapes of objects in his art, because they made

his dreams real and gave pleasure to those eyes of his that so hungered after every sign of

beauty. The secrets of art lie, after all, more within the vision than in expression. That

Rossetti could have directed his genius into another manner from Pre-Raphaelitism seems

possible from the fact that in his poetry so many styles meet and show his variegated

temperament expressing itself in opposing forms. What was of literary significance in

Rossetti's art perhaps gained from Pre-Raphaelitism, for Pre-Raphaelitism made things

symbolical. To nearly every object that they brought into their pictures the Pre-Raphaelites

gave meaning other than its own, other than that which was simply artistic. Now Rossetti,

looking on his art and its relationship to life from a literary more than from an artistic

standpoint, striving to attain in art not an imitation of life but an expression of his ideas

about it, found, as we have said, painters' problems a difficulty. He was irritated by

difficulties which to a whole-hearted painter present pleasures of conquest in proportion to

their resistance to his craftsmanship and skill. In other ways Rossetti lacked the

characteristics of really great painters as such ; he had not the seeing eye that gives to

every outward thing a shape and colour already formed within the mind. From such a cult of the

eyes as this comes the true painter. By taking thought art does not become a metaphor for

ideas, though the whole aim of its subject may be to make it so. Art is always metaphorical,

whatever its subject and however unconsciously, to itself. The presence of genius only is

needed. Yet because in actual pigment red can never be anything other than red, ideas

are clothed more easily in the colour of words, for in themselves

words have no colour and they have no existence other than the existence which they have in

thought, and the colour which any language lends them.

Rossetti could not learn painting instinctively as he learnt writing ; for him the materials

were not so simple, they remained during a long apprenticeship an obstacle rather than an aid

to impassioned expression, and from his apprenticeship he never emerged into anything

approaching freedom. Upon the vivacity of the imagination in them, and not upon subtlety of

line or of observation, the claims of Rossetti's drawings rest, though it is wonderful how

often he lifts his art up to the level of all that he has to say and imposes upon us a

forgetfulness of its shortcomings. His studies do not reveal a master who looked upon objects

and beautiful forms for their own sake and for the sake of the tender drawing he could find in

them. Rossetti, indeed, loved a visible world, and liked to interpret the beauty of natural

objects, but he was always in haste to get the scene set where such objects were, after all,

for him only as accessories to the thing enacted, or as notes in an orchestration; of value but

not existing by themselves. He gave to every object the import of the drama in his mind; in his

art things seem to have about them the meaning lent them by an imagination that spiritualised

objective things so that they seem there in essence only and rendered with a sympathy that

shows how alive to the significance of outward beauty Rossetti was, and how his own time and

every-day surroundings were fused and blent with his most far-reaching imaginings. To turn to

outward things, and to study them as merely offering various surfaces to the light, holding

depths of shadow, possessing lines of delicate shape, was, however, impossible to his

temperament. The characteristic story of Madox Brown setting in early days the young Rossetti

down to paint such still life as

jam jars, and of the young

painter's impatience, shows that to paint or draw the objects for their own sake only was not

congenial to him. There was very likely sufficient of the true painter in Rossetti to make such

study a delight, had his mind ever been still enough for his hand to playfully carry out such

problems; but always at the back of his mind, at the back of the world for him, a strange drama

of love and beauty went on. How then could time be spent in studying what, after all, were

merely objects, how could time be spent in deliberating over the study of them ? And so the

drawings which Rossetti left us are seldom studies of poses and draperies, such elaborate

scaffolding as

that upon which the art of Burne-Jones was built. They are little

pictures in most cases, in which the pencil or the pen afforded a readier and less laboured

means of realising quickly the life dramatic of imagination.

Illustration essentially suited his genius in so far as in small dimensions it was easier to

reflect easily, whilst the power of creation lasted, what was moving in a mind that was held by

no one mood for long. It suited his genius also because it minimised the labour of creation,

and with Rossetti it was always apparent that creation was a labour. He himself has said in

that other art in which perhaps he always found his happiest expression—

- Unto the man of yearning thought

- And aspiration, to do nought

- Is in itself almost an act,—

- Being chasm-fire and cataract

- Of the soul's utter depths unseal'd.

A body that grew faint under the strain of over-feverish genius undoubtedly imposed its

indolence upon Rossetti's spirit, so that he shirked the difficulties of his earlier subjects

until the downfall of his art set in with the constant production, for indiscriminating

purchasers, of a face that grew more and more distant from the beautiful type of his earlier

inspiration, which till the end he always pathetically imagined himself to be creating.

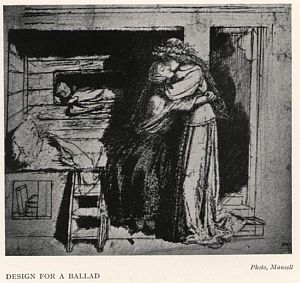

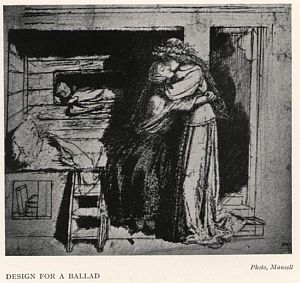

Turning to the illustrations, that called

A Drawing for a Ballad

, with its free and loose handling, its qualities of selection and emphasis, show how

great in many ways Rossetti was. What lines could be simpler than those in the girl's dress ?

In such a sketch as this, in the little things, Rossetti is masterly, and one cannot here

separate what he has to say from the saying of it. This sketch shows an artist great enough to

be unpretentious, and it shows that the happy qualities of mind, uriited with its craft, sprang

from his habits of thought. We see in it with what natural tenderness he has sketched, how by

one of the girl's hands her companion's face is lifted to the kiss. This naturalness holds the

secret of Rossetti's power. His art was consciously set on decoration, but this is not a

decoration ; in all that he has read into the miniature faces and in the embracing of the

hands, we get in this sketch more intimately than anywhere else evidence of his great heart.

This dramatic sympathy would attract every one could it shine more often through the

carelessness, the unhappiness, that at the end obscured it. In this way we must think of

Rossetti as a failure, and a great man cannot fail once without blinding the world to his many

successes. Had Rossetti possessed

no sense of colour, and had he not completed many large pictures and

elaborate illustrations, but only followed this one path as far as he could go, doing only such

things as this, without being a poet and without being a painter, who knows to what extent we

should have praised him for these slighter things alone? There is no doubt that we expect so

much from him, and he has given us so much in other ways, that we forget the treasures hidden

here. One could wish that he had always worked in his drawings with the freedom indicated in

this sketch, but it was not the fashion then. Work in Rossetti's day had to come into the

market elaborated to the point of its soul's extinction in order to be taken seriously. Now

that we have taught ourselves always to value first any indication of the spirit, what would we

not give to possess. ourselves of work by this artist in impulsive drawings, and it must have

been within Rossetti's power to do them down to the last.

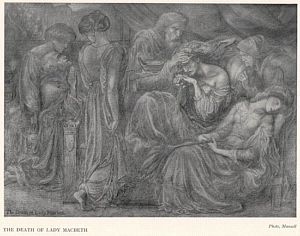

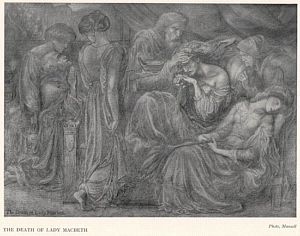

The drawing of the

death of Lady Macbeth is one

of the most wonderful things Rossetti ever did, and it is characteristically marred by

imperfect drawing. The drawing is of great quality throughout, except for the figure with head

averted. Some wonder why the ability to make the rest of the picture perfect failed the artist

here. It is probably because the action of each figure is controlled only by the imaginative

impulse that sways the whole composition, that gives to every part of it dramatic intensity as

if executed all in one mood, bringing in one moment of creation the whole to life on paper.

Those in sympathy with the nature of Rossetti's art do not count this piece of bad drawing a

disastrous flaw. The rarity of genius makes them accept everything gratefully; it disarms a

cavilling attitude. The fault in their eyes even seems to add to the tense note struck as a

changed note in an over sweet harmony. Its dissonance breaks the monotonous rhythmic

decoration, and its harshness relieves the detail so delicately wrought. Rossetti is of the

extreme few who have finished minutely without sacrificing the qualities of greater

significance than finish. His art is great enough to make us forget the detail and to render us

for the time oblivious of it. In our absorption in the subject it seems for a time not to

exist, only the tense mood exists, the intense moment. In a picture in which the moments are

aflame with tragedy Rossetti drew this figure moving slowly and with decorative convention. All

the figures are controlled by such a convention; they are partaking in a high drama. Such a

convention as Irving has in the art of acting gives something to the dignity of tragedy. The

conventions of Rossetti too are so much in the spirit of high

art, they conform so well to the claims of art, that they lend beauty

to that power of his of giving to his drawings dramatic perfection. In regard to the particular

figure of which we write it is better, faulty as it is, than if it had been redrawn in another

mood and given again to the picture. It is to be regretted, of course, that it did not come

rightly as it is, but it is less to be regretted than if he had substituted dead perfection for

living imperfection, a studied and acquired idea of the pose in place of the instinctive one.

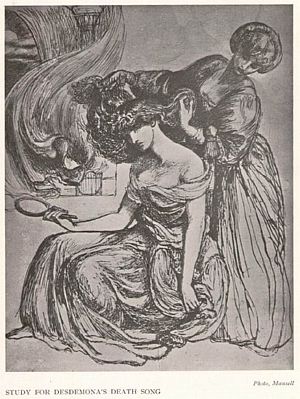

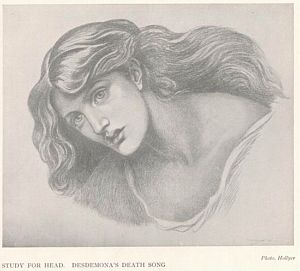

The first illustration for

Desdemona's Death

Song

is simply a rough sketch, but even taken as such it shows how blind or how careless

in the matter of form Rossetti at times could be. Here the lower part of the figure is so

obviously lacking in proportion that it prevents us accepting an otherwise characteristic

drawing as such. Still of Rossetti's best moments is the controlling grace of the bend in the

maid's wrist, and the movement of her head as she combs Desdemona's hair. The curtain blown

into the room by the wind is one of those touches Rossetti gives everywhere ; by insistence on

such an incident he makes us live the moments depicted in his pictures-just as we find

ourselves in moments of extreme tension watching eagerly something absolutely trivial and

making some accident portent with meaning.

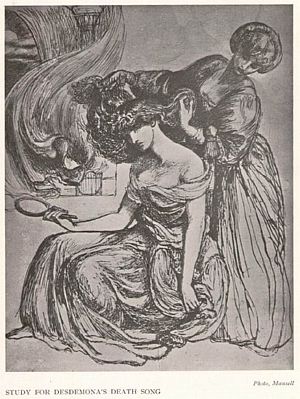

In the

second and completer study for this

picture

we find the proportions corrected; thought and after-thoughts have developed the

artist's intentions. Desdemona, with her hand hanging thoughtfully, is an improvement on her

attitude at first. The maid, however, has lost much of the spontaneity of her original

gestures.

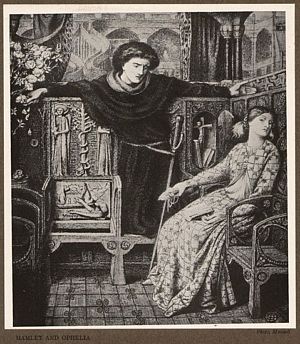

Like all those in whose art we find phases of an extraordinary beauty Rossetti could often

draw in the most uninspired fashion, presumably where his interest flagged. In the drawing

of

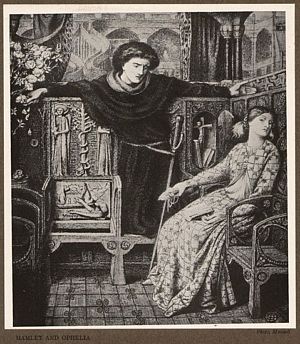

Hamlet and Ophelia, Ophelia is charming; but

it is with difficulty that we are reconciled to the Hamlet; it is difficult even to understand

in what position the figure is standing; not that this indefiniteness often matters in art, but

here, where everything else is so precise, it provokes dissatisfaction. From Rossetti alone

could have come the background with the winding ways parting and meeting rhythmically with

steps up to the bridge. Such architecture as this, and all the quaint furniture in his

pictures, were designed by himself. From his facile imagination anything might come. Certain

objects that were full of associations of old things he returned to often in his drawings, such

as old Books of Hours with all the sentiment that many hands had given to them. The niche in

the picture containing the Crucifix and the Breviaries is significant of the Religion in

Rossetti's art.

This was his religion, to think of Divine things by the legends of a

romantic Church.

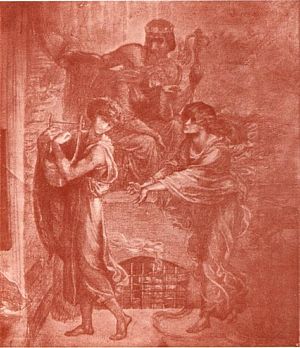

In comparing the

study for

Christ at the House of Simon the Pharisee

with the

completed drawing, the

question arises whether, with the elaboration that has come into the latter, some of the

intensity of the study has escaped ; or whether, on the other hand, the subject has gained. The

simplicity of the first undoubtedly possesses something which is subsequently lost in

elaboration, and yet taking the completed picture and looking into it one finds a lesson in

Rossetti's methods. We find that by dwelling upon his subject he has emphasised certain notes,

has repeated as it were a refrain, and made more spirited and poetic in rendering the figure of

the lover in the foreground. After-thoughts have given every touch that could possibly enrich,

and, at the same time concentrate, dramatic motif in this figure. The embroidery on his coat,

the flowers in his hair, the hair itself, and the face so mocking and fascinating and sure of

itself, is more in the spirit of the subject than the gentler face as it appears in the sketch.

The figure of the Magdalene gains in many ways as completed, and though the distressed loving

face and the flowing hair of the

sketch

are changed, the alteration of the expression on the face from one of intense distress to one

of proud determination is very interesting as showing how his subjects grew and changed under

his hand. It is wholly to the gain of the picture the different gesture which he has arrived at

in the

second drawing, where the

Magdalene with both hands throws the flowers from her hair. The dramatic quality upon which we

have insisted as part of Rossetti's art is nowhere better shown than in the deer quietly eating

leaves from the wall, all unconscious that there is acted out beside it the most pathetically

beautiful drama of the world. One misses in the

finished picture some of the sensitive drawing given in the

sketch to the Magdalene's dress. Here, instead, her clothes are

as if she were perfectly still they give no indication of her movements and the stormy action

round her. That is the fault of Pre- Raphaelitism—to fritter away the spirit for the

sake of the embroidery upon the body's clothes: to lose emphasis in elaboration, to sacrifice a

greater beauty for a meaner one.

Certain characteristics that are strongest in Rossetti's art are the outcome of the intensely

human course his imagination took. His drawings are of the kind that one can live with long;

looking into them often one is always rewarded by finding some new thing, and one's thoughts

are ever being arrested by new appreciation of some

quaint conceit. The depths of Rossetti's imagination are such in these

drawings that we may look into them whilst watching the changes of our own thought.

The best that art has given to us has often come from artists in a quite sub-conscious way.

Because Rossetti's genius was so many-sided it is probable that he could explain most of what

he did to himself, and if in the picture of which we have been speaking we take such a thing as

the alterations between the figures in the background, and as they are shown in the sketch, it

will seem apparent that he gave reasons to himself for everything in his compositions, and did

not drift into anything by accident in aiming at design. In the

sketch the nearest figure pursues the Magdalene beckoning, in

the

finished drawing her movements are

arrested, she and the other figures pause before the door, speechless with cynical amusement

and surprise as the Magdalene enters.

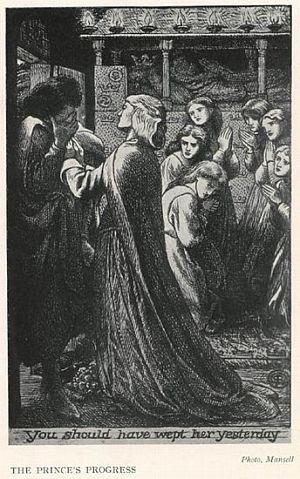

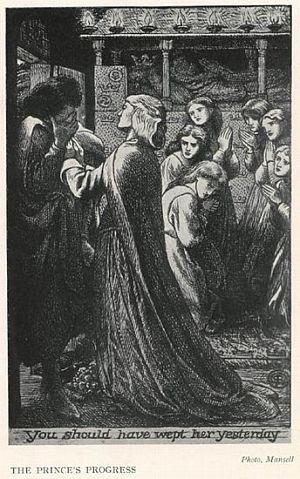

You should have wept her yesterday

was done as an illustration to one of his sister's

poems. It represents the return of the Prince after many delays to find his lady has

died, believing him unfaithful. The ugly drawing of the Prince spoils an otherwise beautiful

design. This ugliness is only compensated for by the six girls who turn their pitiful eyes so

naturally from their prayer to look towards the Prince. The grace of girlhood in their faces

must come as a revelation to some of Rossetti's critics.

The

illustration to Tennyson's “Palace of Art” should excite us as curious and beautiful. We have in it one great poet's illustration

for another's poem, made with perfect art. We have in this drawing the echo of the one's

imagination in the other. Rossetti has brought the drawing on to the paper as a dream. An

immense courage is demanded of the artist, when he shall forget his reason for a dream, and

when he has the courage not to reconcile his dream with the demands of the prosaic mind,

demanding only what is prosaic. The lines illustrated are—

- in a clear-wall'd city on the sea,

- Near gilded organ-pipes, her hair

- Wound with white roses, slept St. Cecily

- An angel look'd at her.

The drawing interprets, and it is wonderful that it should do so, the imaginative mood in

which we feel these lines were written. Like music they bring their message in mystical sound.

One accepts their beauty feverishly. In such a mood as they invite reason greets imagination.

The words do not represent things or a place, but a mood and an emotion. In them is just such a

strange and beautiful

medley as music brings to us, as great art always makes reasonable to

us.

One thing we must not forget in criticising Rossetti, and that is that we are speaking of one

who was among the first to enter into the inheritance of his age, that on these grounds his art

is placed amongst the arts which in every age live by reason of their significance.

Commemorated in Grecian art is the perfected form of man as the flower of animal evolution.

With this perfection attained another day of creation was begun and is continued, in which the

things of the spirit are being built up until the perfect spirit is made. And just as it was

long before man so far awoke to a knowledge of the beauty which triumphs in him as to worship

his own shape (placing before himself his own image as the standard to which the gods had led

him, and from which he might not go back without fear of their displeasure) so not everywhere

yet is the spirit of man learning its own beauty from the consciousness of itself to which it

has attained.

Such art as Rossetti's, with its subordination of everything to an emotional and spiritual

motive, does certainly anticipate, as other modern work like the sculpture of Rodin

anticipates, the direction in which the greatness of art in the future must tend. That which is

concerned with character, with all that outwardly gives indication of the soul, has appeared

and re-appeared triumphantly throughout the history of art—a spirit changing its

raiment. The art of Rossetti fails just in so far as its craftsmanship is a failure, but its

imperfections cannot take away its significance. Christianity made the spirit visible and took

serenity from the face of art. To-day Art is spiritualising itself by its refinements. It is

perfecting itself through such an impressionism of the senses as we have in the art of

Whistler, and through the science of the impressionists of France. Their subtleties are based

on the broad truths given by masters long ago, and fearful lest any sources of our inspiration

should be forgotten what is modern in art has in turn assumed almost every antique shape.

An old manner of painting which was great, does not share its greatness with the modern

imitator, but it does not necessarily withhold it from him. Art may clothe itself in some old

style, as Rossetti's did, and what shape it takes, whether based on the old or growing out of

the new, does not matter when it is the messenger of inward things.

And since no beauty of bodily form greater than Grecian beauty, is possible to art, that art

will be great which betrays the spirit's

Editorial Note (page ornament): Page ends with ornament depicting the head of Hermes in profile, wearing a winged

helmet.

flame. The future of life and of art are one. It is inevitable that art shall be

great as the spirit of man grows rich. It is for this that we have left behind the serenity

which was of Greece and of the partly awakened soul.

PERMANENT REPRODUCTIONS OF THE PICTURES AND STUDIES OF DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI,

G.F. WATTS, O.M., R.A., AND SIR EDWARD BURNE-JONES ARE PUBLISHED BY FREDK. HOLLYER, 9

PEMBROKE SQUARE, KENSINGTON, W. ILLUSTRATED CATALOGUE 12 STAMPS

![Image of page [21]](http://www.rossettiarchive.org/img/thumbs_small/s255d.wood.jpg) page:

page: [21]

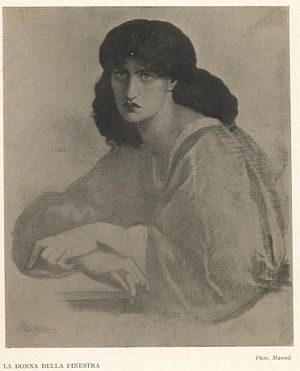

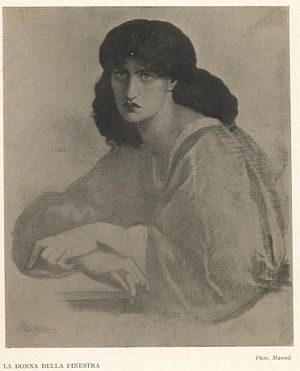

LA DONNA DELLA FINESTRA

Photo, Mansell

Figure: Monogram and date lower left corner: ‘1870’. . . . Finished

drawing (from Mrs. Morris), differing in treatment. Half-length, turned to the left, head

and eyes facing to front, and hands placed upon a ledge in front of her; the heavy dark

hair, fastened behind the ears, lies outspread on the shoulders.Surtees, p. 152

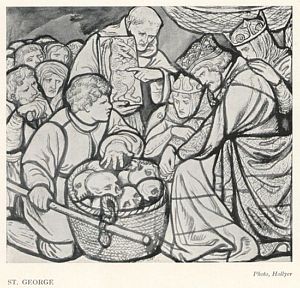

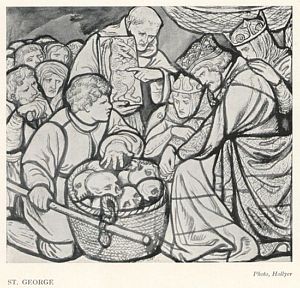

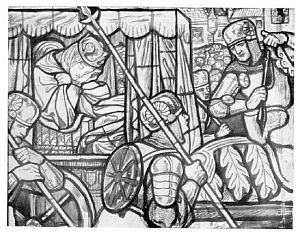

ST. GEORGE

Photo, Hollyer

Figure: Ink design for stained glass; basket of skulls in foreground surrounded by figures,

including seated king at left.

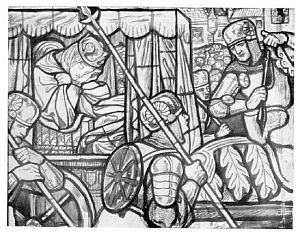

ST. GEORGE

Photo, Hollyer

Figure: Ink design for stained glass; Princess in a palanquin at left with eyes closed and

cheek resting on her crossed hands. Mounted soldier at right, soldier with lance in

foreground, half-figure soldier at lower right.

DANTIS AMOR

Photo, Mansell

Figure: Inscribed around the sun: ‘

QUI EST PER OMNIA SAECULA BENEDICTUS’; around the moon: ‘

QUELLA BEATA BEATRICE CHE MIRA CONTINUAMENTE NELLA FACCIA DI CLOUI’; along the diagonal dividing line: ‘

L'AMOR CHE MUOVE IL SOLE E L'ALTRE STELLE’;. . . . Love, dressed as a pilgrim, stands full-face holding a

sundial dated ‘1290’. In the upper left corner the sun (head of

Christ); lower right corner a crescent moon (head of Beatrice). The background is divided

diagonally between the sun's rays and the stars.Surtees, pp. 73-4

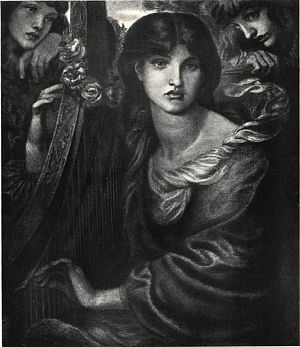

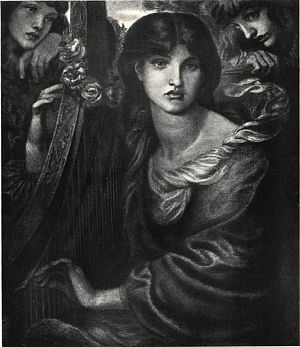

LA GHIRLANDATA

Photo, The Autotype Co.

Figure: Alexa Wilding sitting for the woman, and the angel heads taken from May Morris. . .

. Monogram and date lower left corner: ‘1873’ . . . Finished study

for the picture, lacking only the foliage and foreground flowers.Surtees, p. 130

THE PRINCE'S PROGRESS

Photo, Mansell

Figure: The prince is being stopped by a woman. In the background the dead body of the

Princess lies in state under a canopy surmounted by flaming torches; below it six mourning

girls kneel at a praying desk.Surtees, p. 108 Captioned by the line ‘You should have wept her

yesterday’.

Note: Heavy pink laid paper.

STUDY FOR THE SALUTATION

Photo, Hollyer

Figure: Finished study of Mrs. Morris for head and shoulders of Beatrice. Head almost to

front.Surtees, p. 155

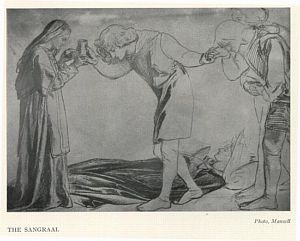

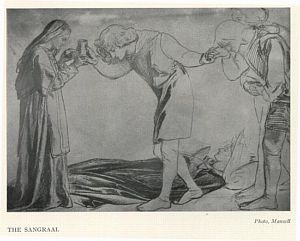

THE SANGRAAL

Photo, Mansell

Figure: Unfinished study with only the five principal figures participating; their

disposition is similar but the action of the two knights is different: Sir Bors lays his

left hand on Sir Percival's left shoulder, while clasping the latter's left hand with his

right. Red chalk outlines for the two circular windows are visible but are disregarded by

the superimposed figures . . . According to W. M. Rossetti the head of the central figure

was done from Swinburne (the likeness is not particularly striking) whom the artist met

for the first time at Oxford while painting the Union murals. The Angel of the Grail bears

the features of Elizabeth Siddal.Surtees, p. 53

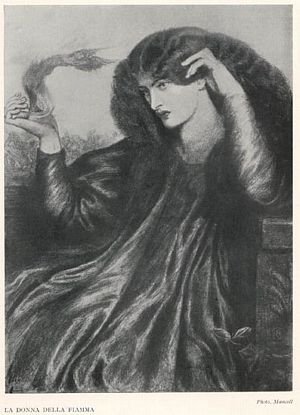

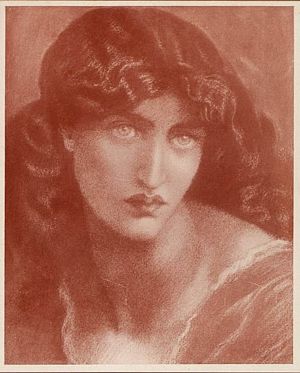

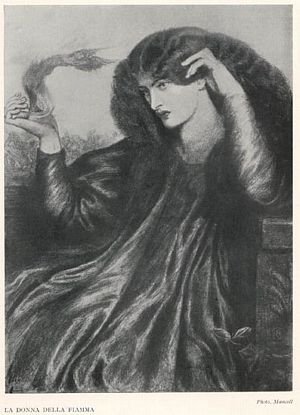

LA DONNA DELLA FIAMMA

Photo, Mansell

Figure: Initials and date lower right, ‘1870’ . . . Finished drawing,

probably a study for a painting which was never realized. The head is taken from Mrs.

Morris; from her right hand issues a winged figure in a flame of fire; on her left wrist

is a circular mark.Surtees, p. 122

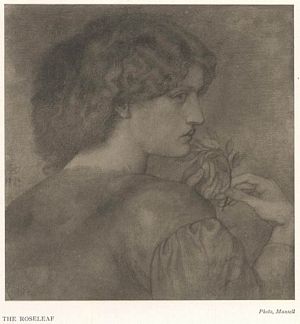

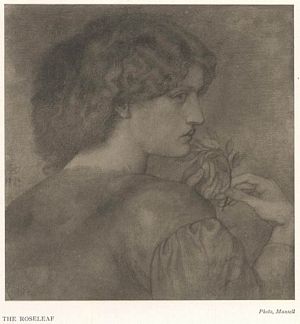

THE ROSELEAF

Photo, Mansell

Figure: Monogram and date left centre: ‘1870’ . . . Head and shoulders

of Mrs. Morris turned to right, holding up a spray of rose-leaf with her right hand and

fingering it with her left.Surtees, p, 122

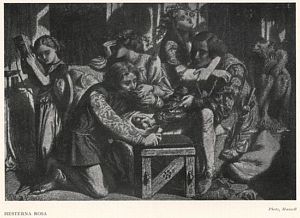

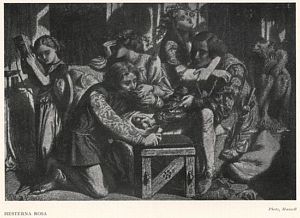

HESTERNA ROSA

Photo, Mansell

Figure: Interior of a tent at dawn after a night of revelry. A child playing upon a lute

stands on the extreme left and on the right a hairy ape is scratching itself (symbols of

innocence and depravity) whilst ‘Yesterday's Rose’ has turned away

her head and hides her face with her right hand.Surtees, p. 21

N.B.: Wood (or Mansell) crops the picture so that the inscriptions along the

bottom do not show. Also, the plate in Surtees shows the addition of a date, 1858, next to

the signature at the lower right. This date does not show up on the plate in Wood.

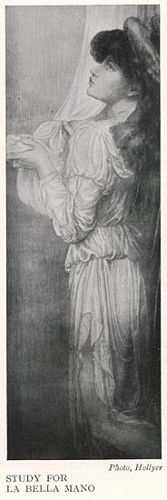

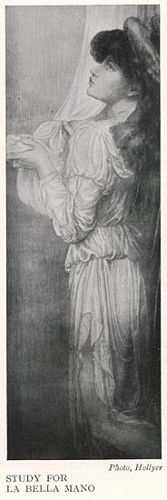

STUDY FOR

LA BELLA MANO

Photo, Hollyer

Figure: Right-hand attendant angel, in the act of offering a towel. Nearly whole-length,

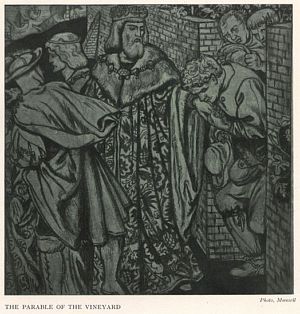

wearing soft drapery; the head is raised in profile to left.Surtees, p. 139

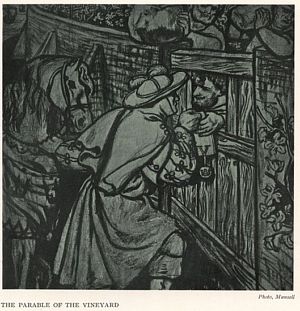

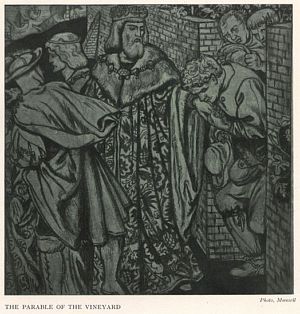

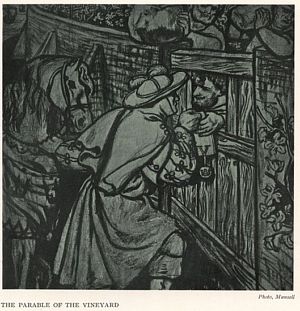

THE PARABLE OF THE VINEYARD

Photo, Mansell

Figure: Seven figures total: three men in medieval clothing planting vines; two women

looking on from upper left; two male figures wearing crowns looking over the fence at upper

right.

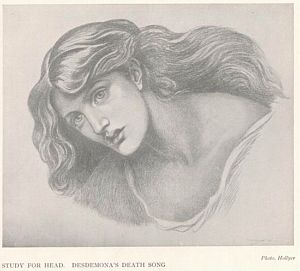

STUDY FOR HEAD. DESDEMONA'S DEATH SONG

Photo, Hollyer

Figure:

Study for head of Desdemona, three-quarters to left, inclined downwards with hair

falling upon the shoulders, eyes looking up, lips parted; drapery indicated.

Probably taken from Mrs. Stillman.

Surtees, p. 151

STUDY FOR DESDEMONA'S DEATH SONG

Photo, Mansell

Figure: Desdemona seated and having her hair combed out by Emilia. . . . [Desdemona's] right

arm, holding the looking-glass, is extended forward; her left arm hangs at her side.Surtees, p. 150

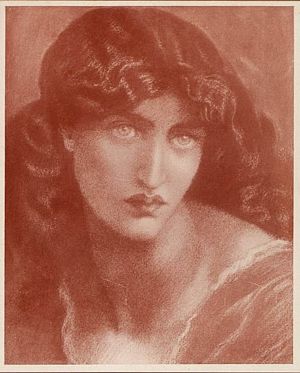

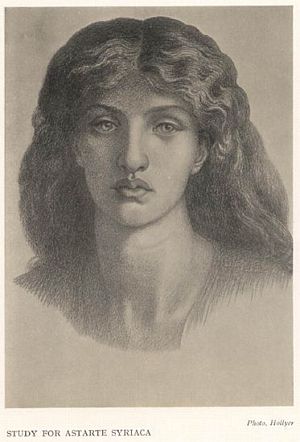

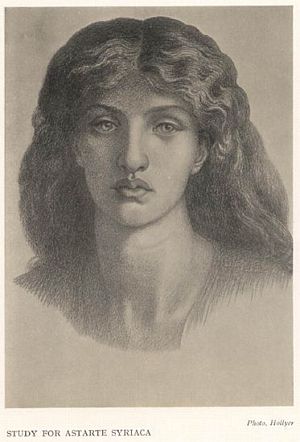

STUDY FOR ASTARTE SYRIACA

Photo, Hollyer

Figure: Full-face head and shoulders of a woman with long, loose, dark hair.

MARY AT THE DOOR OF SIMON

Photo, Hollyer

Figure: Monogram and date lower left corner: ’1870‘ . . . Design for a

large oil-painting, commissioned by Leyland, but never begun. Identical in its composition

to the version of 1858 but for the absence of the fawn and background figures.Surtees, p. 64

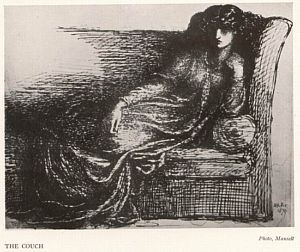

THE COUCH

Photo, Mansell

Figure: Dated lower right: ‘29 Nov. 1870’. On the right end of a sofa

facing to front with her left elbow propped on a bolster, and knees drawn up. Her right

arm is laid at length along the side of her body.Surtees, p. 177

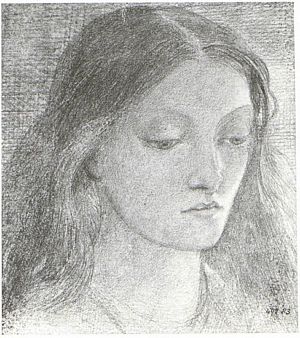

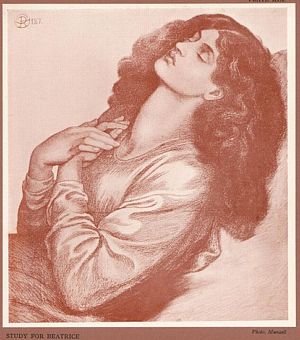

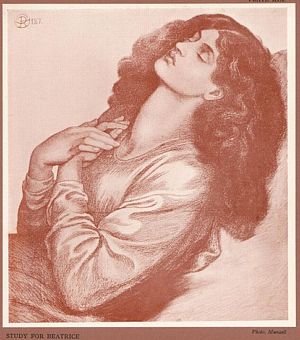

STUDY FOR BEATRICE

Photo, Mansell

Figure: Monogram and date upper left corner: ‘1871’. Study for

Beatrice. Half-length to left; her eyes are closed; hands folded on her breast; the heavy

dark hair falls about her shoulders.Surtees, p. 145

SKETCH OF MISS SIDDAL

Photo, Mansell

Figure: Seated at an easel, turned to the left. In her left hand she holds a mahlstick, and

in her right a paintbrush.Surtees, p. 194

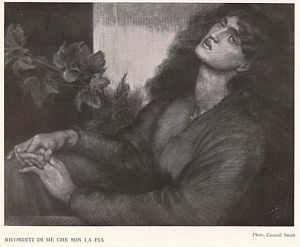

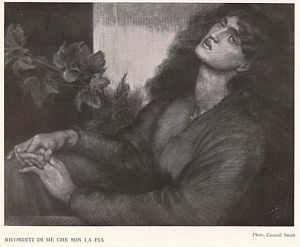

RICORDITI DI ME CHE SON LA PIA

Photo, Caswall Smith

Figure: Here Mrs. Morris is reclining, with head thrown back. The arms lie along the body,

hands claped on the knees, fingering her wedding ring. Foliage in the background.Surtees, p. 119

THE PARABLE OF THE VINEYARD

Photo, Mansell

Figure: The head of William Morris is clearly recognizable in the opening of the gate,

wearing ‘a smile of hypocritical civility’. Behind him, two men are

in the act of dropping stones, the right-hand one bearing a resemblance to Gambart the art

dealer, the one on the left to Val Prinsep, and not to Morris as Treffry Dunn suggests.Surtees, p. 83

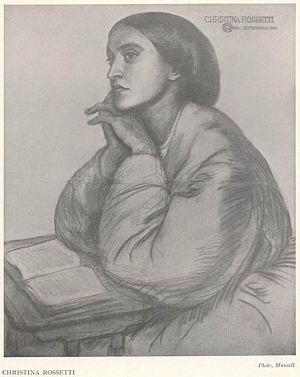

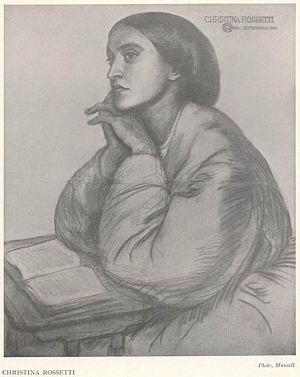

CHRISTINA ROSSETTI

Photo, Mansell

Figure: Inscribed upper right with the sitter's name, monogram and date: ‘del

September 1866’. . . . Over half-length turned to the left, seated at a table

leaning her chin on folded hands; the head is nearly in profile; a book lies open before

her.Surtees, p. 184

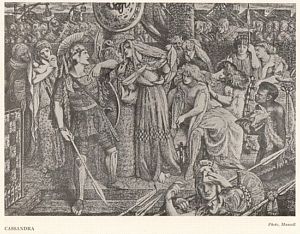

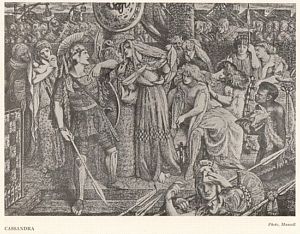

CASSANDRA

Photo, Mansell

Figure: It is an elaborate composition full of power and urgency and not without humour. A

note of pathos is introduced in the whole-length figure of Andromache clutching her naked

baby, and in Hecuba standing on the right, her hands over her ears while Pram tries to

comfort her. Special note should be taken of the pattern formed within the confined space

of the background where Trojan soldiers are marching to battle, forming a design with

their helmets and raised spears more usually provided by Rossetti's angels' heads within

enclosed wings.Surtees, p. 80

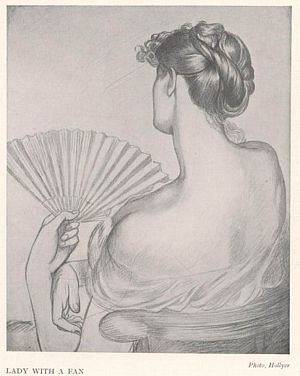

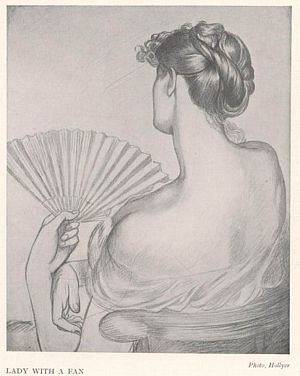

LADY WITH A FAN

Photo, Hollyer

Figure: Half-figure seated, back view, wearing drapery leaving the shoulders uncovered. Her

hair is drawn up and twisted into a chignon, a tendril escaping down the nape of the neck.

She holds a fan in her left hand.Surtees, p. 124

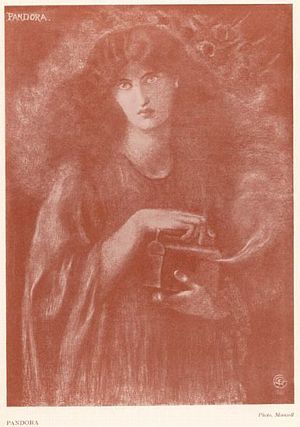

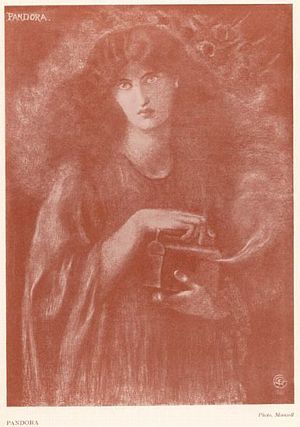

PANDORA

Photo, Mansell

Figure: With both hands she holds the fateful casket encrusted with precious stones . . .

from out of it issues . . . smoke curling upwards round her head, taking the shape of

spirit forms. The head is taken from Mrs. Morris. . . . Monogram and date lower right

corner: ‘1869’.Surtees, pp. 125-6

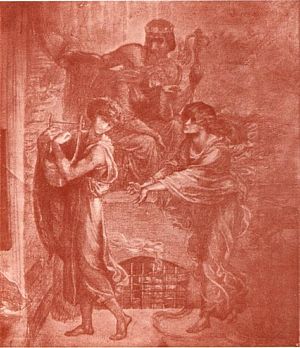

ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE

Photo, Mansell

Figure: The subject is taken from Virgil's descriptions of Orpheus leading Eurydice out of

Hades, over the Styx, and giving the forbidden backward glance. Enthroned behind them are

Proserpine, a shrouded lamenting figure, and Pluto, who draws aside a curtain revealing a

stairway leading up to earth.Surtees, p. 141

THE PALACE OF ART

Photo, Mansell

Figure: Design for Moxon's illustrated edition of Tennyson's

Poems (1857),

illustrating the lines from

The Palace of Art. . . . In the woodcut the

angel is kissing St. Cecilia on the forehead (as in the Ashmolean version) while here he

is looking down at her.Surtees, p. 48

LACHESIS

Photo, Mansell

Figure: A woman [Elizabeth Siddal] seated in a chair in profile to left with her right hand

raised, appears to be unravelling a knitted garment lying on her knees.Surtees, p. 81

Note: Heavy brown laid paper.

HAMLET AND OPHELIA

Photo, Mansell

Figure: Highly finished drawing . . . illustrating the incident in Act III, Sc. i, of

Shakespeare's play where Ophelia, here seated in a small oratory, is in the act of

returning to Hamlet the letters and presents he has given her. Depicted on the upturned

misericord seat beside him is the death of Uzzah after touching the Ark of the Covenant;

the back panel is as elaborately carved with the Tree of Knowledge encircled by a crowned

serpent; on either side an angel stands with uplifted sword, and in the space between them

is inscribed: ‘Eritis sicut deus [

sic]

scientes bonum et malum.’ (It is of interest to note here that the

decoration carved on the seat corners is the one adopted by the artist for many of his

frames.) From a turret in the upper right corner the King and Queen look down.Surtees, p. 61

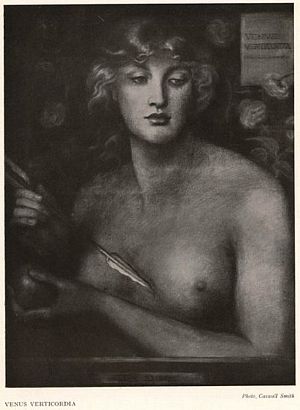

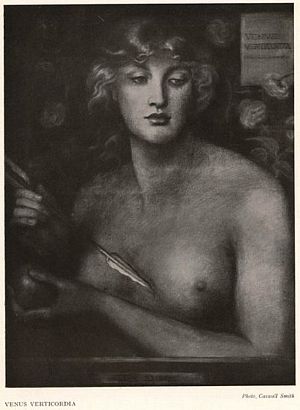

VENUS VERTICORDIA

Photo, Caswall Smith

Figure: Venus stands naked . . . in her hand an apple—the reward of her

beauty—and a dart. . . .Initials and date: ‘AD 1867’ on a

narrow white cartouche, lower centre. Title inscribed on a label upper right. . . . [T]he

figure behind a balustrade stands slightly to the left, the position of the hands being

slightly altered in consequence. The lowered eyes look to right; the hair falls on the

left shoulder. . . . Halo and butterflies omitted, also the flowers, except for a few

roses climbing up the background trellis.Surtees, p. 99

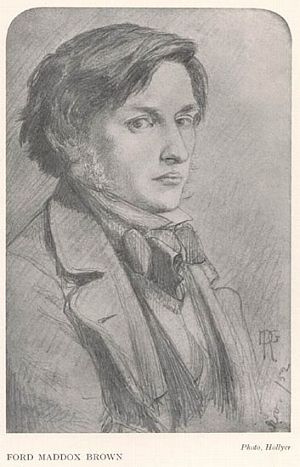

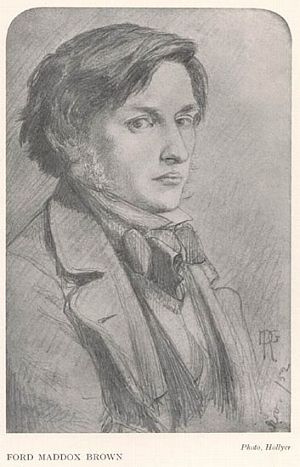

FORD MADDOX BROWN

Photo, Hollyer

Figure: Monogram and date lower right: ‘Nov/52’. . . . Almost

half-length, turned three-quarters to right.Surtees, p. 158

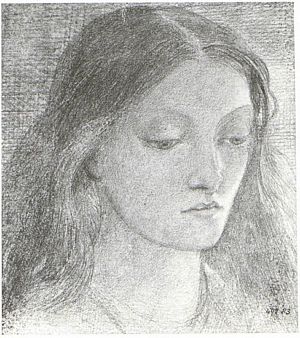

MISS SIDDAL

Photo, Hollyer

Figure: Head with unfastened hair turned three-quarters to right, looking down under heavy

lids.Surtees, p. 195

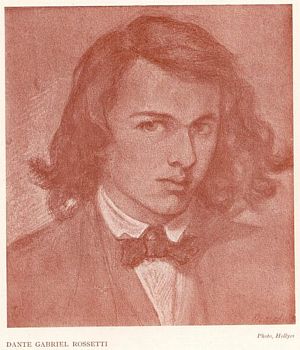

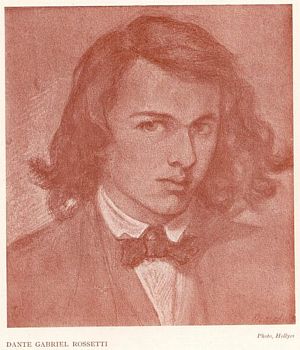

DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI

Photo, Hollyer

Figure: Dated lower right: ‘March 1847’. Head and shoulders; the head

turned sligthly to the right, the eyes to front. The hair is long, curling at the ends.Surtees, p. 185

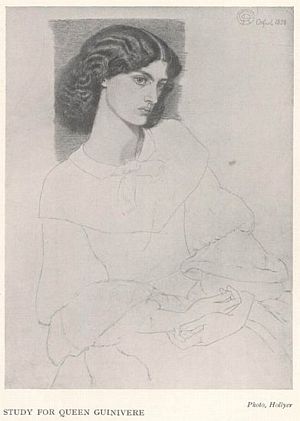

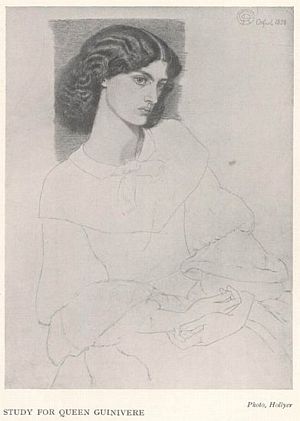

STUDY FOR QUEEN GUINIVERE

Photo, Hollyer

Figure: Monogram and date inscribed upper right: ‘Oxford 1858’. A

study for Queen Guenevere in one of the Oxford Union murals which was not carried out; it

is therefore listed as a portrait. Ten years later Rossetti was to use the same pose for

his studies of Mrs. Morris as Mariana . . . Seated, over half-length, turned to the right,

her left shoulder raised, her hands placed in her lap; only the head, inclined slightly

forward, is finished.Surtees, p. 174

STUDY FOR DESDEMONA'S DEATH SONG

Photo, Mansell

Figure: Desdemona, seated, right arm extended, elbow on her knee, palm facing downward, left

hand holding a mirror. Emilia stands behind her, combing her hair out. Desdemona's bare left

foot is visible. In the background at right are candlestick and a crucifix with a figure of

Christ. N.B.: This drawing does not appear in the Surtees catalogue.

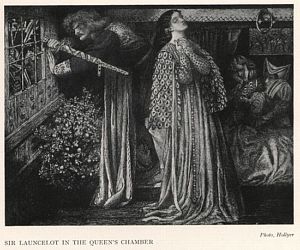

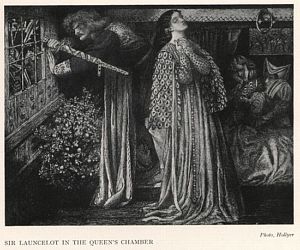

SIR LAUNCELOT IN THE QUEEN'S CHAMBER

Photo, Hollyer

Figure: Launcelot with his sword stands at the window at left; weapons are visible through

the window. Guenevere stands facing away from the window, her hands at her throat. Three

figures cower at right.

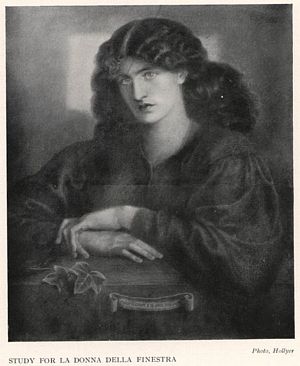

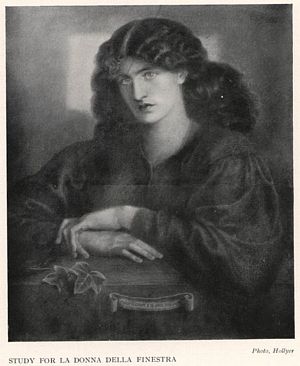

STUDY FOR

LA DONNA DELLA FINESTRA

Photo, Hollyer

Figure: Half-length woman facing front, dark hair down to shoulders, hands folded on a

surface in front of her. Monogram and date upper right corner: ‘1870’. Inscribed on a

scroll in the centre foreground: ‘Color d'amore e di pietà

sembiante’ . . . Study with accessories omitted except for two ivy leaves lying

on the ledge. (From Mrs. Morris.)Surtees, p. 152

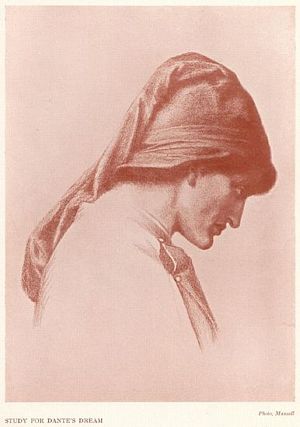

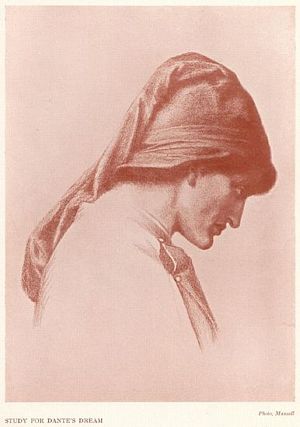

STUDY FOR DANTE'S DREAM

Photo, Mansell

Figure: Study for head and shoulders of Dante; head downturned, wearing a medieval

head-dress. His cloak is buttoned on his right shoulder.Surtees, p. 45

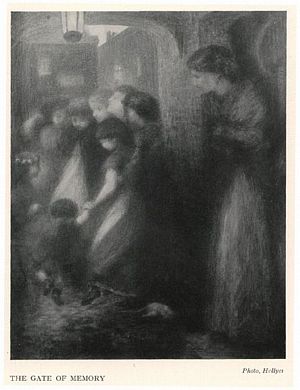

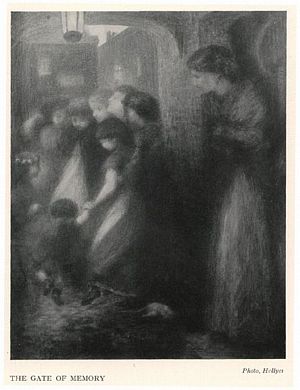

THE GATE OF MEMORY

Photo. Hollyer

Figure: On the right a prostitute stands at dusk under an archway, watching a group of

dancing children, and recognizes herself as once she was in the figure of a seated,

flower-crowned child. An over-hanging lamp casts a dull yellow light upon the children and

illuminates for a moment a large rat as it scuttles out of sight. Fine houses with lighted

windows supply the background to this somber and poignant drawing.Surtees, p. 56

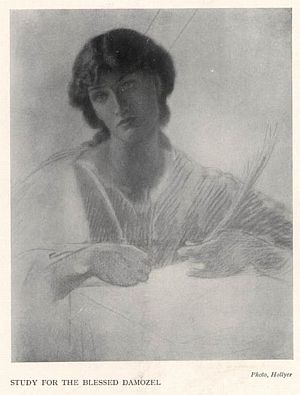

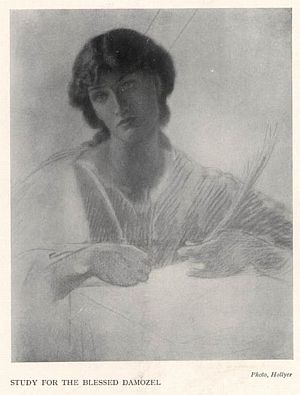

STUDY FOR THE BLESSED DAMOZEL

Photo, Hollyer

Figure: Alternative study for the central figure. Head and bust with hands (of which only

the head of Alexa Wilding is finished) facing to front, the head inclined slightly to

left. The action of the hands is close to that in the painting; a palm branch is roughly

sketched in her left hand.Surtees, p. 143

Note: Heavy brown laid paper.

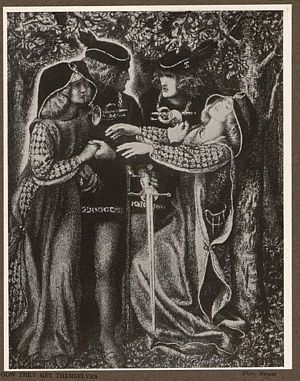

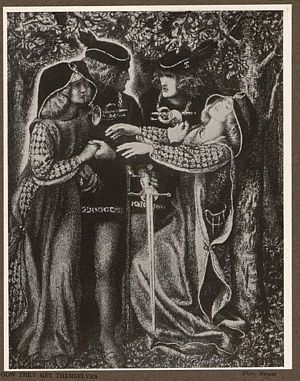

HOW THEY MET THEMSELVES

Photo, Mansell

Figure: monogram and date lower right corner: ‘1851 1860’. . . .

Called by Rossetti the ‘the Bogie drawing’, it ilustrates the legend

of the Doppelgänger which had fascinated him since childhood. A pair of lovers

meet their doubles, outlined in light, in a wood at twilight— a sure presage of

death.Surtees, p. 74

THE LADY OF THE GOLDEN CHAIN

Photo, Hollyer

Figure: Portrait of Mrs. Morris, partly unfinished.Surtees, p. 120

THE DEATH OF LADY MACBETH

Photo, Mansell

Figure: Title inscribed in the lower left-hand corner. Seven figures, including Lady Macbeth

sitting up in a bed at center, her hands clasped in a mad gesture.

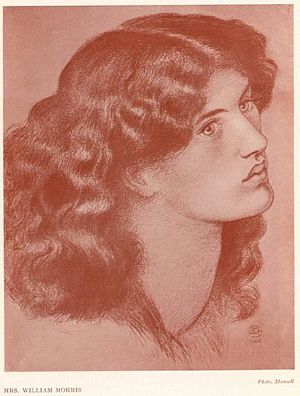

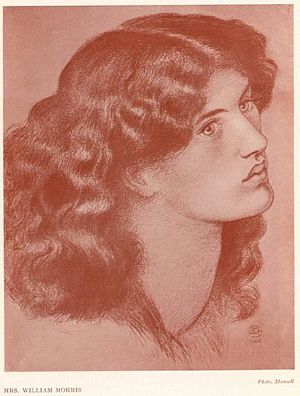

MRS WILLIAM MORRIS

Photo, Mansell

Figure: Monogram and date lower right: ‘1865’. Head upturned,

three-quarters to right; the hair loose about the shoulders.Surtees, p. 175

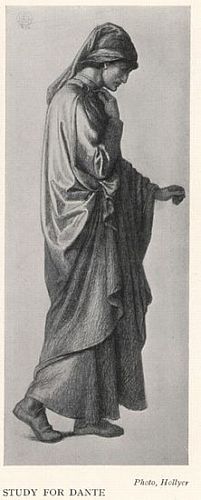

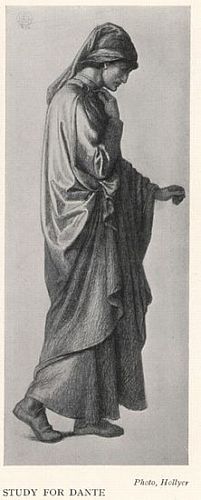

STUDY FOR DANTE

Photo, Hollyer

Figure: Monogram and date upper left corner: ‘1874’. Study for Dante,

most probably for the picture with date added later. Whole-length walking to the right

with his left arm extended and his right raised to his neck . . . his right arm gathers up

his cloak.Surtees, p. 44

DESIGN FOR A BALLAD

Photo, Mansell

Figure: Two sisters embracing; behind them, a baby lies in a niche in the wall.

THE PARABLE OF THE VINEYARD

Photo, Mansell

Figure: Six figures in medieval dress; a bearded and crowned figure in a patterned cloak

with a fur collar stands at center; at right is the wall of the vineyard with three figures

within the gate.

![Image of page [21]](http://www.rossettiarchive.org/img/thumbs_small/s255d.wood.jpg)