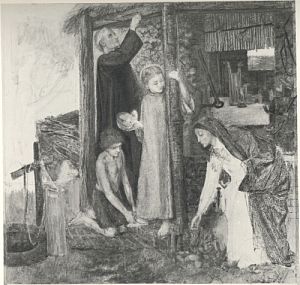

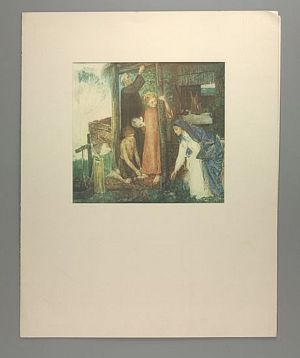

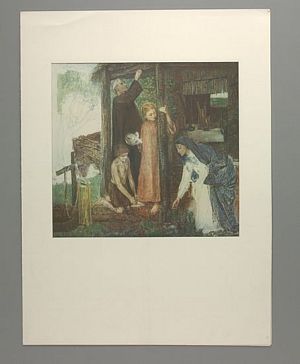

Description: DGR described this watercolour in his note to the

accompanying poem (published in the 1870

Poems

):“The scene is in the house-porch, where Christ holds a bowl of blood

from which Zacharias is sprinkling the posts and lintel. Joseph has brought the lamb and

Elisabeth lights the pyre. The shoes which John fastens and the bitter herbs which Mary is

gathering form part of the ritual.” But not all of these details are in the

picture, which DGR left unfinished: in particular, neither Joseph nor Elizabeth appear in the

scene. Surtees' comments pick up other important details: “By the opening of

the well on the extreme left two pieces of wood tied together with string form a Cross to which

the water-cask is attached. The opening framed by a vine, behind the foreground figures,

reveals a table in an interior, set with bread and wine” (

vol. 1, 40).

Copyright: ©Tate Gallery, London 2001

Scholarly Commentary

Introduction

DGR's letter to Coventry Patmore about the picture is quite important: “Its chief claim to interest, if successful when complete, would be as a subject which must actually have occurred during every year of the life led by the Holy Family, and which I think must bear its meaning broadly and instantly—not as you say ‘remotely’—on the very face of it,—in the one sacrifice really typical of the other.” The event interests DGR because it illustrates his belief that spiritual agency must be “inherent in the fact.” His picture, he says, “differs entirely from . . . the very many both ancient and modern which resemble it in so far as they are illustrations of Christ's life ‘subject to his parents,’ but not one of which that I can remember is anything more than an entire and often trifling fancy of the painter, in which the symbolism is not really inherent in the fact, but merely suggested or suggestible, and having had the fact made to fit it”( Correspondence, 55.54).

The picture thus helps to explain both the difference and the continuity between his early work, with its Christian preoccupations, and his later work, where pagan materials get more elaborated. DGR is interested in Christianity because it is a mythos of real spiritual presence and not of merely symbolic forms; and he is interested in “Pre-Raphaelite” or Medieval Christianity because he saw in that culture the signs of a belief in real spiritual presence. For DGR, the Renaissance (and its attendant religious reformations) represented a great collapse of spiritual values and the emergence of “soulless self-reflections of man's skill” in art and culture.

DGR is not a Christian, for he is as interested in pagan and polytheist spiritual presences as he is in Christian and monotheist ones. The double interest is evident early, most especially in the work that centers in Arthurian and stil novisti materials. So in a picture like The Passover in the Holy Family, while the literal focus is Christian, the predominant concern is with incarnation as such.

Such works raise important aesthetic issues. DGR values and imitates the European primitivists for one crucial reason: their art demonstrates a belief in real spiritual presence. This means for DGR that the artistic practice is itself a spiritual agency—it does not observe from a distance, and in perspective, but possesses what he called an“inner standing point.” Works like The Passover in the Holy Family therefore function as acts of artistic homage, and thence as arguments for a devotional art determined to function sacramentally. Because pagan eroticism formed a crucial element in his devotional beliefs, however, a work like this, lacking a strong erotic element, does not fully express what he wants his art to execute. The picture is therefore largely intellectual and programmatic, like The Girlhood of Mary Virgin .

The work transcends its own conceptual horizon in two respects, however. First, its lack of finish proves a distinct strength, as it does in Giotto Painting the Portrait of Dante . Particularly striking is the crude earthiness emanating from the figure of the Virgin bending to pick the herbs. Her head is stylized and even hieratic, but it is attached to a body that has scarcely emerged from the picture's rawest materials. Second, the figure of Zachariah painting the posts and lintel with blood is highly suggestive. The cathonic basis of the Passover and its Christian type, the Crucifixion, begins to emerge precisely because of the picture's rough materiality. Furthermore, Zachariah's ritual action can be seen as an idiosyncratic emblem of DGR's cultic and magical ideal of painting.

Production History

WMR says that a picture on this subject was begun in 1849 ( Preraphaelite Diaries and Letters, 231). It was to have been the central panel of a triptych with the left and right panels showing the “Virgin planting a lily and a rose, and the Virgin in St. John's house after the crucifixion” (WMR, Preraphaelite Diaries and Letters, 216-217). DGR did not carry this project through, however, and left off the Passover picture until 1854, when Ruskin saw a pencil drawing and a black chalk drawing. From these he commissioned DGR to finish the Passover picture. DGR then worked on the picture through 1855-1856 ( Ruskin, Rossetti, Preraphaelitism, 29-30). Ruskin was not happy with DGR's continual revisions, as his letter to Ellen Heaton of November 1855 shows (quoted in Surtees1, 41), and he eventually removed the picture from the painter's hands in 1856 in order to prevent further alterations. The picture, left unfinished, nevertheless supplies “a remarkable insight into the artist's working methods,” as Grieve has noted (274).

Reception

Ruskin's interest in this picture made it a fairly well-known work in DGR's lifetime.

Iconographic

For DGR the picture treated the Passover in“its actuality as an incident no less than as a ‘scriptural’ type” ( Correspondence, 55.54). The patent symbolic character of the picture, however, seemed “too remote and unobvious” to Patmore, and wholly nonsymbolic to Ruskin ( Ruskin, Rossetti, Preraphaelitism, 139-140). Bentley shrewdly observes “that Rossetti's essentially Catholic conception of ‘scriptural types’ or figurae—learned, very likely, from Dante—is in direct opposition to the spirit of Protestant literalism” (28). All of the painting's accessories relate to the redemptive action that gets played out in the life and death of Jesus.

Pictorial

DGR was well aware that his picture bore near similarities to “very many both ancient and modern” pictures. He insisted on the special character of what he was trying to represent: “not one of [these other pictures] that I can remember is anything more than an entire and often trifling fancy of the painter, in which the symbolism is not really inherent in the fact, but merely suggested or suggestible, and having had the fact made to fit it” ( Correspondence, 55.54).

Literary

The subject takes up the prescriptions for the rites of the Passover, as set out in Exodus 12:1-13. It then reimagines these rites as they would have been performed by the family of Mary and Joseph, and in the context of the typological significance that would arise under those circumstances.

Bibliography