![Image of page [frontispiece]](http://www.rossettiarchive.org/img/thumbs_small/s173.r-1.s.jpg) page:

page: [frontispiece]

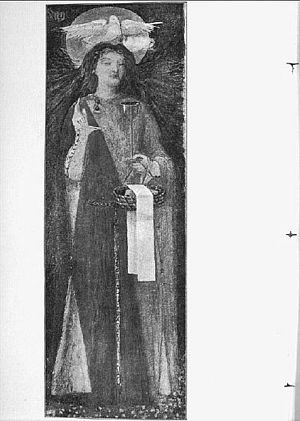

Venus Verticordia.

D.G. Rossetti, pinx.

Walter L. Colls. Ph. Sc.

Figure: Replica of

Venus Verticordia.

“Venus stands naked amongst a mass of

honeysuckle and cluster of pink roses ... in her hand an apple ... and

a dart .... Minor variation in the action of the dart and the pose of

the hands, also in the fall of the hair, here worn in a fringe on the

forehead; the butterflies on the halo omitted, but one is poised on

the apple.”

Surtees, p. 99-100

DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI

By

F. G. STEPHENS

Author of

“Celebrated

Flemish and French Pictures”,

“Landseer”, etc.

Note: There is an insignia included which is oval in design with ornamental

laurel leaves surrounding it to form a rectangle. In the center is

the title of the series (of which this work is a part) and the name of the

editor, all surrounded by elaborate scrollwork. Below this are two

circular head and shoulders portraits in three-quarter profile. Text

in illustration: THE PORTFOLIO. Artistic Monographs Edited by

P. G. Hamerton. Raffaello / Sanzio, Rembrandt / Van Rym.

London

Seeley and Co. Limited, Essex Street, Strand

New York, Macmillan and Co.

1894

DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI

PAINTER AND POET

NOWHERE in Time's vista, where the forms of great men gather

thickly, do we see many shapes of those who, as painters and as poets

have been alike illustrious. Among the few to whom, equally on

both accounts, conspicuous honours have been paid, none is superior to

Rossetti, of whose genius doubly exalted the artists say that in design he

was pre-eminent, while, on the other hand, the most distinguished poets

of our age place him in the first rank with themselves. As to this pro-

digious, if not unique, distinction, of which the present age has not yet,

perhaps, formed an adequate judgment, there can be no doubt that with

regard to the constructive portion of his genius Rossetti was better

equipped in verse than in design.

It is certain that our subject looked upon himself rather as a painter who wrote than as a verse-maker who painted. It is

probable

that the very facility, which, of course, had been won with enormous

pains, and was maintained with characteristic energy and constant

care, of his literary efforts led Rossetti to slightly undervalue the rare

gifts of which his pen was the instrument, while, as to painting, his

hard-won triumphs with design, colour, expression, form, and visible

beauty of all sorts seemed to him the aptest as well as the most successful

exponents of the passionate poetry it was, by one means or the other, his

object to make manifest. His mission was that of a poet in art as in

verse, and, by devoting the greater part of his life and all his more

arduous efforts to the former means, he made it plain that, notwithstanding all obstacles, the palette served his purpose

better than the pen.

I refer thus emphatically to Rossetti's genius in its double form as well as to the inevitable division of his energies which

attended that

circumstance, because, while I wonder at his achievements and know how

great were the powers he employed, I cannot help thinking that a less

complex nature than his would have done still more than, so far as time

and space allow, these pages have to report of and illustrate.

Gabriel Charles Dante was the elder son, and, his sister Maria

Francesca being his senior, the second child of Gabriele Rossetti and

Frances Mary Lavinia, his wife, born Polidori; she wrote some poems

and educational books of value, and died several years ago. William

Michael, third child of this union (born in 1829), is the still living

accomplished writer on poetry and art, and the tenant of a high post in

the Inland Revenue Department, Somerset House. The fourth child

is Miss Christina Georgina Rossetti (born 1830) whose

Goblin Market

attests her to be one of the most distinguished poetesses of this

century. Gabriele Rossetti was descended from an Italian family of

some renown, whose original name was Della Guardia, and he was

born in 1783 at Vasto d'Ammone, in the Abruzzi, the son of one

Domenico, who was connected with the iron trade of that town.

Gabriele, a man of culture, whose specialty was in profound studies of

Dante—whence one of the names of his elder son—removed to Naples,

and held an honourable office as custodian of antique bronzes in the

then Bourbon Museum of the capital. This post and all his other

possessions were forfeited in 1820, when he joined in revolutionary

movements against Ferdinand I., King of the Two Sicilies, which, by

the aid of the Austrians, were defeated and the chiefs proscribed. Among

them Rossetti took refuge at Malta in 1822, and, ultimately, in London,

where he arrived in 1825, and in the next year married the above-named

lady, who was a daughter of Signor Gaetano Polidori, a secretary of

Count Alfieri, the Italian poet and supposed second husband of Louisa

of Stolberg, Countess of Albany, wife and widow of Charles Edward

Stuart, the besotted Young Pretender. The wife of Signor Gaetano was

a Miss Pierce, an Englishwoman. Besides the lady who became Mrs.

Gabriele Rossetti, Gaetano had for his son Dr. Polidori, one of Lord

Byron's physicians, with whom his lordship fell foul in a certain

Epistle

from Mr. Murray

, and who, with other things in verse and prose,

wrote a sanguinary novelette called

The Vampire, which still retains its

shadow of a reputation. Arrived in London Gabriele Rossetti maintained

himself as a teacher of his native tongue, and succeeded so well in that

capacity that the Professorship of Italian in King's College was offered

to him and accepted in 1831.

As might be expected of one possessing so many accomplishments and

whose career had been marked by so much courage, the professor was a

man of striking character and aspect, so that when I was introduced to

him in 1848, and his grand climacteric was past, and, as with most

Italians, a life of studies told upon him heavily, I could not but be

struck by the noble energy of his face and by the high culture his

expression attested, while a sort of eager, almost passionate, resolution

seemed to glow in all he said and did. To a youngster, such as I was

then, he seemed much older than his years, and while seated reading at a

table with two candles behind him and, because his sight was failing,

with a wide shade over his eyes, he looked a very Rembrandt come to

life. The light was reflected from a manuscript placed close to his face,

and, in the shadow which covered them, made distinct all the fineness

and vigour of his sharply moulded features. It was half lost upon his

somewhat shrunken figure wrapped in a student's dressing-gown, and

shone fully upon the lean, bony, and delicate hands in which he held

the paper. He looked like an old and somewhat imperative prophet,

and his voice had a slightly rigorous ring speaking to his sons and

their visitors. Near his side, but beyond the radiant circle of the

candles—her erect, comely, and very English form, and face remarkable

for its noble and beautiful matronhood, and but half visible in the

flickering glow of the fire—sat Mrs. Rossetti, the mother of Dante

Gabriel. He too, leaning his elbows upon the table and holding his

face between both hands so that the long curling masses of his dark

brown hair fell forward, sat on the other side, his attenuated features

sharply outlined by the candle's light.

It is not certain whether the scene which thus impressed my

memory was presented at No. 38, Charlotte Street, Portland Place,

one of those then very “respectable,” but dull, and now much deteriorated

opposing lines of brick walls, with rectangular holes in them, which

Londoners call houses, where, on the 12th of May, 1828, our subject

was born, or whether No. 50 in the same street was thus signalised.

To the latter house the Rossetti family migrated about the time in

question. It is fortunate that a “Board” has not, as in many neigh-

bouring regions, changed the numbers of the houses in Charlotte Street,

and that its monkey-like activity has, for the present at least, spared

the record of a famous family. Nevertheless, the birthplace of the

Rossettis will, doubtless, some day be marked with an honourable white

stone. Certain it is that they were all born at No. 38, and that in

April, 1854, at No. 50, the ardent self-sacrificing patriotism of Pro-

fessor Gabriele Rossetti found its earthly close. Tennyson's “long

unlovely” Wimpole Street, where the Laureate was wont to stand waiting for the

- hand that can be clasped no more,

and which is close to our poet's birthplace, is not more “bald,” than that

which took its name from the ill-favoured wife of George III. Rossetti

was christened Charles after Mr. Charles Lyell, his godfather, of Kin-

norchy, Fife (whose more famous son wrote

The Principles of Geology),

Gabriel, after his father, and Dante after the illustrious poet. We know

that his first teaching was due to his mother, an accomplished and devoted

matron whose affection was, even to his latest days, ceaselessly acknow-

ledged by her son. Mr. Knight tells us the lad's first school was under

the Rev. Mr. Paul, in Foley Street, whence, in 1837, he was with his

brother, removed to King's College School, where he stayed till 1843,

and received all the advantages of that capital academy; these, however,

did not include what are now called “sports,” a circumstance which of

course had not a little influence on his character in after life.

1

Transcribed Footnote (page 8):

1 It has been said that Rossetti shared at least some of the athletic proclivities and aptitudes of British youth, and was

accustomed to enjoy energetic exercises. This is

quite a mistake, for, although he was in youth a tolerably good walker, he never excelled

in that respect. It was an error which has made him appear as a rower; indeed, I

remember when in my boat he proposed, because it was in his way, to throw over-

board one of the stretchers (!); he never cared to swim, and, if he rode at all, he could

not be called a rider. The fact is that, when he pleased, which, until his later days,

was both often and long, no one worked harder than Rossetti; but, as a glance at his

frame and face amply attested, his energy was not physical. In after life he deplored

his youthful neglect of school games and struggles of the more manly kind.

At King's College School the Italian professor's son acquired, as his

brother tells us, “an education in Latin, French, and the rudiments of

Greek.” Italian was, of course, his customary, if not his native tongue;

to these collectively considerable attainments must be added a “certain

knowledge of German,” which was more than enough to enable him to

read in that language. After some tentative and rather “boyish”

literary efforts, resulting in an experimental drama, and a prose romance

or two, one of which was printed by his grandfather, Mr. Gaetano

Polidori, Rossetti determined to become an artist. This was in the

autumn of 1843, a date which, however, must not be taken as that of

the youth's beginning to draw. Indeed, his brother tells us that our

subject was even then a member of a sketching club, and the same

authority still possesses some drawings made in ink to illustrate a

story of the designer's, called

Sorentino

, by means of which, by the way,

he even thus early appears in that double capacity of author and artist

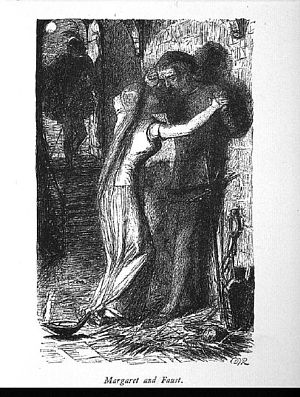

which always obtained with him. The influence of Retzsch and his

once-famous

Outlines anent

Faust was manifest in all the productions of

this category by Rossetti, as well as all his colleagues of the P-R.B. who

could draw, that is six of the seven. Every one of these was accus-

tomed to make designs in this manner. Thus, some of the finest

“inventions” of Sir John Millais's most brilliant youth were, with

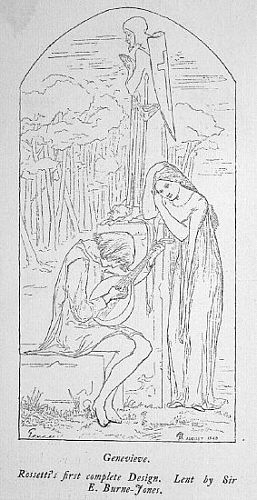

stringent care and delicacy, put upon paper. That influence is manifest

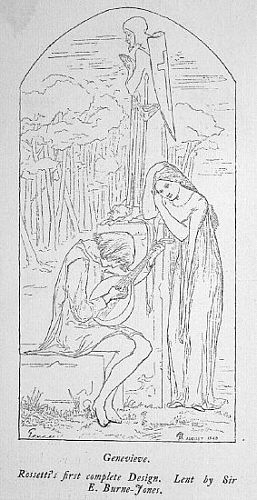

in the beautiful outlined design called

Genevieve

, which charms us

in this text, and has not been reproduced till now.

There is no doubt that Rossetti's systematic training as an artist was

begun in 1843, and at Mr. Cary's then well-known academy, which

stood at the south-east corner of Charlotte Street and Bainbridge Street,

Bloomsbury. It was a capital drill-ground for drawing from the

antique, beyond which step of his training Rossetti did not pass in that

place, including drawing from the human skeleton, but not painting.

Here, with frequent excursions into the realms of poetry proper, he

remained, I fear, in a somewhat desultory mood, rather less than three

years, during which period he prepared the drawing of a statue, then

demanded by the Royal Academy ere its tyros were admitted as

Probationers to the Antique School in Trafalgar Square. In July, 1846,

he was admitted a Student of the Academy. “I saw,” says a fellow

student, “Rossetti, whom Fame of a sort had preceded, enter the school

with a knot of Probationers, who, as if to keep each other in coun-

tenance, herded together. All their forerunners turned, as was natural,

to the door of the room, and noticed among the freshmen the saturnine,

thin, and for a youth of nearly eighteen, not well-developed tyro other

‘Caryites’ had talked of as a poet whose verses had been actually

printed, and whom they described as a clever sketcher of chivalric and

satiric subjects, who, in addition, did all sorts of things in all sorts of

unconventional ways. Thick, beautiful, and closely curled masses of

rich brown much-neglected hair, fell about an ample brow, and almost

to the wearer's shoulders; strong eyebrows marked with their dark

shadows a pair of rather sunken eyes, in which a sort of fire, instinct of

what may be called proud cynicism, burned with a furtive kind of energy,

and was distinctly, if somewhat luridly, glowing. His rather high cheek-

bones were the more observable because his cheeks were roseless and

hollow enough to indicate the waste of life and midnight oil to which the

youth was addicted; close shaving left bare his very full, not to say

sensuous, lips and square-cut masculine chin. Rather below the middle

height, and with a slightly rolling gait, Rossetti came forward among his

fellows with a jerky step, tossed the falling hair back from his

face, and, having both hands in his pockets, faced the student world

with an

insouciant air which savoured of defiance, mental pride and

thorough self-reliance. A bare throat, a falling, ill-kept collar, boots

not over familiar with brushes, black and well-worn habiliments,

including, not the ordinary frock or jacket “of the period,” but a very

loose dress-coat which had once been new—these were the outward and

visible signs of a mood which cared even less for appearances than the

art-student of those days was accustomed to care, which undoubtedly

was little enough. Apart from all these unconventionalities one saw at a

glance that the partial slovenliness of the newcomer was far from being a

sign of mere vanity affecting pride and, in contempt for others, seeking

to be singular.” It must be remembered that Rossetti had all his life been

accustomed to meet in his father's house poets, scholars, and patriots of

mark. When he entered the Academy he was by no means unknown,

many a “Caryite” had preceded him from Bloomsbury, and not a few

turned to welcome him to the Antique School.

In that school Rossetti worked somewhat less than was desirable,

intermittently, and as if without a serious intention to profit by it to the

utmost; nor did he ever pass to the higher grades of the Life and

Painting Schools. It is clear that literature, abundant reading and

writing poetry were his chief delights till about March, 1848, when,

much stirred by the vigorous and noble design of Madox Brown's

Parisina

, which he saw at the British Institution in 1845, and thus

strengthened impressions due to the same fine artist's contributions to

the Westminster Hall Exhibitions of 1844 and 1845,

1 and, above all,

to the pathos and originality of Brown's picture in the “Free Exhibition”

at Hyde Park Corner in 1848, he wrote to the latter expressing the

highest admiration of his works, and begged for lessons in painting, in the

technique of which our subject had, it is beyond question, made no con-

siderable progress. This appeal was made in such enthusiastic terms that

as, with a great deal of humour, Brown was wont to tell in after years, the

recipient fancied such compliments were not unlikely to cover an inten-

tion to “make fun” of him. Brown therefore, before calling on his

would-be pupil, provided himself with a thick stick and sallied forth,

intending to use it if need be. To Charlotte Street he went, and seeing

“Mr. Rossetti” on the doorplate was partly reassured, but held to the

cudgel until the young Rossetti's manifest sincerity disarmed all sus-

picion and, finally, impelled Brown so warmly that he then and there

undertook the office of a teacher, not for fees, but entirely for the love of

art, and in order to be helpful to one so anxious and so deeply moved.

Rossetti himself was wont gleefully to tell his intimates that the first

result of Brown's teaching was dismay, because the subject set before

the pupil for accurate and stringent imitation was a group of jars,

such as pickle-pots, or some such things, in still life, the uncom-

promising prose of which did not suit the aspirations of the tyro.

Nevertheless, there can be no doubt whatever that to Brown's guidance

and example we owe the better part of Rossetti as a painter

per se,

although his will to study with tenacity, and thus command success,

might have been stiffened by the encouragement and example of Mr.

Holman Hunt, apart from which, I fear the latter-named student was not

Transcribed Footnote (page 11):

1 These were

The Body of

Harold brought to the Conqueror

, a cartoon, 1844, and

Justice, 1845.

the fittest guide for a genius like Rossetti, who very soon departed from

the uncompromising principles of the indomitable friend who had neverbeen, even for an hour, his model in art. Rather had

the brilliant and

happy power of Millais, one of the truest painters of the age and a

born artist, been as light before the subject of these pages. Rossetti

was considerably behind his friends. Brown was his senior by seven

years, and a thoroughly trained artist, who had exhibited in this country

in 1841; Millais was a Gold Medal Student in the Royal Academy

before the foundation of the P-R.B., and an exhibitor in 1846; while

Mr. Holman Hunt, an exhibitor from the last-named year, had passed

through ordeals of practice and training of the most self-exacting

stringency, far beyond what Rossetti, although he had never departed

from the conviction that his chief function was painting, and not poetry, had submitted to.

Desiring to become a thoroughly trained painter, Rossetti wrote to

Brown. It appears that, with greatly increased admiration of Brown's

skill and genius, Rossetti had seen besides

Parisina

, and other instances

at the British Institution, that artist's contribution to the “Free

Exhibition of Modern Art,”

1 which in the spring of 1848, was formed

near Hyde Park Corner. This noteworthy and epoch-marking instance was named

The First Translation of the Bible into English

, or, more aptly,

Wickliffe reading his Translation of the New Testament to Johnof Gaunt. Painted in 1847-8, it was No. 216 at the gallery in question, where it attracted much attention, aroused abundant controversies,

and, above all, allowing for the idiosyncrasies of the artist, was the first Pre-Raphaelite picture of the original stamp

ever produced. It

Transcribed Footnote (page 12):

1 This gallery was afterwards known as the Portland Gallery, and removed to Regent Street, where it survived till 1861. It

was originally held in the

ci-devant Chinese Gallery, Hyde Park Corner, and filled a long, well-lighted brick building standing on a site in the rear of the present

Alexandra Hotel, and originally constructed for the exhibition and sale of Chinese and Japanese

bric à brac. The time not being ripe for an adequate development of that cult of quaintness and strong colour which has culminated in

the wildest Impressionism, so-called, of which we are now witnessing the decline and fall, the Chinese Gallery, as an exhibition,

came to grief in a year or two. It gave way to the “Free Exhibition,” as it was humorously called, because there was nothing

free about it, the artists paying for their places, besides a percentage on the prices of their pictures when they sold them

there, while the public paid forthe privilege of seeing them as well as for the catalogues which described them.

was, of course, exhibited months before the foundation of the Brotherhood in the autumn of 1848, and undertaken while the

P-R.Bs. proper were still in their original darkness. A happy combination of Italian taste, and the technique of the Low Countries

of the pre-Rubensian epoch, the gravity, energy, high finish, and pure and brilliant coloration of this noble piece had, as

I said in the

Portfolio of 1893, p. 66, profound effects upon the painters of the Brotherhood.

It was in the autumn of 1848, that Rossetti, finding the accommodation of the paternal house in Charlotte Street too limited

for his purpose, joined Mr. Holman Hunt (with whom he had not previously been particularly intimate) in renting a studio at

the then No. 7 Cleveland Street, Fitzroy Square, a house which stood next to the south-west corner of Howland Street, before

one reaches the workhouse. It was, even then, a dismal place, the one big window of which looked to the east, and through

which, when neither smoke, fog, nor rain obscured the unlovely view, you could see the damp, orange-coloured piles of timber

a neighbouring dealer in that material had, within a few yards of the room, piled in monstrous heaps upon his backyard. In

this forlorn quarter Rossetti began his first picture in oil that deserved the name, although, as already intimated here,

certain tentative experiments in portraiture with that vehicle had exercised him with more severity than success. Nothing

could be more depressing than the large gaunt chamber where the young artist executed two memorable pictures and from which

posterity must perforce date the inception of Pre-Raphaelitism of the primitive and stringent, not to say hide-bound sort.

Except early in the morning, nothing like that fulness of light which painters now demand was obtainable where the dingy walls,

distempered of a dark maroon which dust and smoke stains had deepened, added a most undesirable gloom. The approach to it

was by a half-lighted staircase up which the fuss and clatter of a boys' school kept by the landlord of the house, and too

often dashed with sounds of chastisement and sorrow, frequently arose; add to these uncomely elements a dimly lighted hall,

surcharged by air of which the damp of the timber yard was not the only source of its mustiness, and a shabby out-at-elbows,

giving access from the street that, even then, was rapidly “going down in the world.” It was sliding so to say, to its present

zero of

rag and bottle shops, penny barbers, pawnbrokers and retailers of the smallest possible capital. Such was the place where

Mr. Holman Hunt, then in his twenty-first year, and Rossetti, who had not completed his second decade, met and began to work

out their destinies. The former, who on that occasion left his father's house, was the master of a good deal less than a hundred pounds, being

the price, or what remained of that sum, for which he had sold to a prize holder of the “Art Union,”

1 his noteworthy No. 804 in the Academy of 1848, entitled

The Flight of Madeline and Porphyro

, an illustration of Keats's

Eve of St. Agnes.

It was an excellent example which, without the least quality of Pre-Raphaelitism, attested the remarkable skill of the artist

and his rare sense of the picturesque in design. He had before this time painted, besides pot-boiling portraits, two or three

less ambitious works.

Rossetti was yet, apart from the studio, a member of his father's family, and, unlike his comrade, still, being so young,

dependent upon his father, but resolutely devoted to art, that is to say to the expression of the poetry of his nature by

means of painting, rather than in verse. It is the more to his honour that, while his facility in verse was rare, brilliant,

and great, he had at this period to undergo agonies of toil and passionately to, so to say, tear himself to pieces, while

he became a painter according to the lofty standards of Madox Brown, Holman Hunt, and John Millais. These, as well as other

friends of his, witnessed the greatness of the struggle and honoured accordingly the

Transcribed Footnote (page 14):

1 This was the now deceased Mr. Charles Bridger, a well-known archæologist and antiquary, whose

Index to Printed Pedigrees has proved the value of his services. The prize was £60 or thereabouts, for the winner being a friend of mine, I negotiated

the business, but forget the exact sum in question.

Transcribed Footnote (page 14):

2 Millais, too, had exhibited at the Academy in 1846, his

Pizarro seizing the Inca of Peru, his

Elgiva (which he sold for £120) in 1847; his picture of

The Widow's Mite, which, with life-size figures, was at Westminster Hall in 1849, occupied this artist in 1848, so that he exhibited nothing

at the Academy in that year. There was no Pre-Raphaelitism in any of these instances, nor otherwise until the painters' contributions

to the Academy of 1849 marked their adherence to the newly pronounced principles of the Brotherhood. In March of this year

Rossetti's

Girlhood of Mary, Virgin

was shown at Hyde Park Corner, and by Brown, his splendid

King Lear

, which is now in the collection of Mr. Leathart, of Gateshead, and, as a powerful illustration of Pre-Raphaelitism a glory

of the English School, worthy to be compared with any masterpiece of Rossetti in his riper days, with

A Huguenot

, or

The Proscribed

Royalist

of Millais.

victor of that strenuous self-contest. Under these conditions, and in the studio here described Rossetti began to paint

The Girlhood of Mary, Virgin

, which is, so far as he was concerned, the first outcome of the Pre-Raphaelite views he had accepted. Whether he had adopted

them under the inspiration of one or more of his friends, or, as some have supposed, had invented them, matters little. That

he took an independent line in regard to art the work in question emphatically affirms; the truth seems to be that Brown's

influence predominated in his studies, while the mysticism of his own mind directed him where neither the dramatic intensity

of Millais and Brown, still less the stringent realism of

Mr. Holman Hunt, had any power. The design was certainly made rather early in 1848, probably before going to Cleveland Street.

How independent that line of thought and art had already become, that is how entirely free from impressions due to any of

those artists of power with whom he was then associated, I could not better demonstrate than by setting before the reader

a very sufficient, but much reduced transcript of Rossetti's design, made in fine outlines and exquisitely drawn, to illustrate

Coleridge's

Love, and having for its text the wooing of Genevieve—

- ;She lean'd against the armed man,

- The statue of the armed knight;

- She stood and listened to my lay,

- Amid the lingering light.

- I played a soft and doleful air,

- I sang an old and moving story—

- An old rude song, that suited well

- That ruin wild and hoary.

If ever pencil gave the tender pathos and suggested the moving

cadences of a poet's verse this lovely drawing, which has never been

reproduced before, does so entirely and sympathetically. Quoting his

brother's own record, a sort of diary, Mr. W. M. Rossetti tells us

that “On August 28 [1848] Rossetti sat up all night, and made,

from 11 p.m. till 6 a.m. an outline of Coleridge's

Genevieve, ‘certainly the best thing I have done.’”

1The drawing was, I believe, produced

Transcribed Footnote (page 15):

1 The choice instance is made in ink, with a very fine, probably crow-quill, pen, and bears, in a monogram, “G. C. D. R., August, 1848.” Not long after this the artist ceased

to use his name of Charles, and thenceforth adopted the style “Dante G. Rossetti,”

or a monogram, of which there is more than one version, comprising “D.G.R.” only.

as the artist's contribution to a rather ambitious body calling itself “The

Cyclographic Society,” according to the rules of

which each member

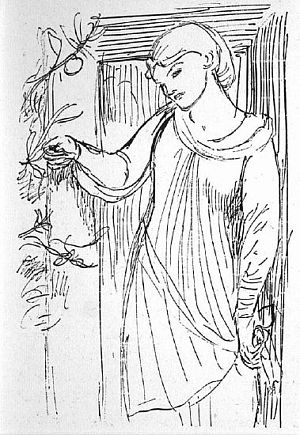

Genevieve

.

Rossetti's first complete Design. Lent by Sir E.

Burne-Jones.

Figure: Standing woman leans against a statue of a knight while

listening to a seated man play the lute.

furnished a design to be placed in a portfolio with others, circulated

and subjected to the criticism of all who chose to offer their

opinions. The design itself was given to Mr. Coventry Patmore who, not

long since, gave it to Sir E. Burne-Jones, to be exchanged for a

drawing by that master himself. It now belongs to Sir Edward, who

generously lent it to illustrate this sketch of his old friend's art.

To return to

The Girlhood of Mary,

Virgin

, the style, gravity, and grace of which are manifest

developments of the like qualities of

Genevieve

,

it is indispensable to illustrate the

leading facts in its history, as the first example of Rossetti as a

Pre-Raphaelite out of which naturally arises an account of the origin

of the Brotherhood bearing that name. Mr. Holman Hunt has in the

Fortnightly

Review

given a version of the

history of the body, which, though not quite complete, is, as far as

it goes, correct. It is to the effect that some time after the two

comrades settled in Cleveland Street, they encountered at Millais's

Sig. B

Note: The final sentence on this page ["In course of time

Collinson, having painted a a remarkable picture..."] contains

a typographic error: the article "a" is repeated.

house in Gower Street, a book of engravings from frescoes in the Campo

Santo of Pisa, that is to say from pictures, the purity, energy,

simplicity, and poetic veracity of which served as points of

crystallisation, or

nuclei of enthusiasm for the

till then somewhat nebulous ideals in art the three men severally and

independently of each other possessed. Then and there, or very shortly

afterwards, the friends determined to form what may be called a League

of Sincerity, with loftier aims than artists generally cared for, a

leading principle of which implied that each confessor should paint

his best with due reference to nature, without which there could be no

sincerity. There was no intention of following, much less copying the

modes and moods of the artists who preceded Raphael, nor of rejecting

anything which had been attained in art's service since the days of

that Prince of Painters. Each friend was to work in his own way, and,

if an edifying use could be made of the subject he chose for his art,

so much the better, yet nothing like a didactic, religious, or moral

purpose was insisted on by any Brother. The enthusiasm of Rossetti

prompted the idea of forming a “Brotherhood,” which in a

very few days was enlarged to include James Collinson, then a painter

of domestic

genre of conspicuous ability and great

promise; Thomas Woolner, a sculptor of rare gifts and prodigious

skill; the present writer, who was then in training as a painter, and

W. M. Rossetti, who acted as secretary to the society. In 1848 none of

these men, except Collinson and Woolner, was more than twenty-one

years of age. Naturally enough, Brown was solicited to become a

Brother, but he, chiefly because of a crude principle which, for a

time was adopted by the other painters, declined to join the

society. This principle was to the effect that when a member had found

a model whose aspect answered his ideas of what his subject required,

that model should be painted exactly, and so to say, to a hair. Such a

hide-bound rule was, of course, an absurdity, destructive of all art

and hopeless. It is not to be supposed that enthusiasm for the right

was the monopoly of the leading trio, or that during several years

after the date in question, any one of the Brotherhood turned aside

from his duty as a member. In course of time

Collinson, having painted a a remarkable picture to which much less

respect than is due has been

awarded, and, being sorely tried by religious influences and a wavering will, openly seceded.

1

Rossetti gallantly began and carried out his beautiful though tentative

Girlhood of Mary,

Virgin

, which represents Mary and her mother, St. Anne, seated at an embroidery frame in a balcony and beneath a vine whose foliage

extended

over a lattice, through which is a view of a landscape without the chamber. In front of the group six books are piled, each

inscribed with the name of a Virtue, while near the volume stands a child-angel, who is watering a tall lily. Joseph is trimming

the vine, amid the leaves of which the Holy Dove is resting in a golden halo. The lily is

not only the Virgin's emblem, but serves as a model for the embroidery she is supposed to be devoutly engaged upon while her

mother tenderly and gravely regards her. The sonnet Rossetti printed in the catalogue of the Free Exhibition describes her

as being

- As it were

- An angel-watered lily, that near God

- Grows and is quiet.

This sentence sufficiently indicates the mystical

and allusive mood of the painter in 1848, as well

as illustrates the devout spirit which the

companionship of Mr. Holman Hunt tended to

strengthen while the counsel

Transcribed Footnote (page 18):

1 Walter Howell Deverell, a much beloved fellow-student,

with artistic gifts time could surely have

developed, was nominated, but not actually

elected, to fill the place of Collinson. He died

February 2nd, 1854, aged twenty-six. Collinson

became a member of the Society of British Artists,

which did not recognize Pre-Raphaelitism in any

of its forms, and, being well advanced in middle

life, died some years since. What Woolner was

expected to do as a Brother I do not exactly know,

but in Art and otherwise he lived a Knight of the

Order of Sincerity, became a Royal Academician

of great renown, and died October 7th, 1892. As

for myself, having been stringently trained in the

practice of Art, I found the experience thus won to

be of great value in the profession of an Art-critic,

into which “gentle craft” I gradually

drifted, and so remain. In the same profession Mr.

W. M. Rossetti has made a position of importance,

besides that to which he holds as a

littérateur.

Ford Madox Brown, whose death occurred October 6th,

1893, left a name we all honour as that of one in

the higher ranks of Art. It appears thus that of

seven young men and Brothers five have attained

eminent positions, four of them being pre-eminent,

although for years after the society was formed no

single member, whatever his position might be,

escaped insult, obloquy, and wicked and malicious

misrepresentation. The more conspicuous the Brother

was the more outrageously was he attacked.

of that artist and Madox Brown helped materially

the execution of the picture which, apart from its

prodigious merits and simply as the first work of a

painter whose training had been both brief and

interrupted, I never cease to look upon with

indescribable wonder. A little flat and gray, and

rather thin in painting, it is most carefully drawn

and soundly modelled, rich in good and pure

colouring; and in the brooding, dreamy pathos, full

of reverence and yet unconscious of “the time to

come,” which the Virgin's still and chaste face

expresses, there is a vein of poetry, the freshest

and most profound. Rossetti had no difficulty in

finding models whose aspects he could delineate

without scruple as fittest for his purpose; his sister

Christina sat for the Virgin, his mother for St.

Anne. The Child-angel was painted from a

younger sister of Mr. Woolner, whose features did,

perhaps, require a little modification. The artist's

descriptive sonnet, above quoted, continued with

the account of the Virgin's girlhood, which lasted

- Till one dawn, at home,

- She woke in her white bed, and had no fear

- At all, yet wept till sunshine, and felt awed;

- Because the fulness of the time was come.”

This passage distinctly points to the next picture of

Rossetti, the supremely beautiful

Ecce Ancilla Domini!

for the

Ancilla

in which the artist's sister again sat, and which again illustrates

the brooding, dreamy pathos of the painter's

mystical mood, as well as the virginal charm of the

lady who sat for its principal figure and face, a

charm to which

The Girlhood of Mary,

Virgin

, as well as the

Ecce Ancilla

Domini!

manifestly owe much, if it was not

actually the prompting

raison

d'être

of

both the works. There is an excellent reproduction

of the latter in the

Portfolio for 1888, with

an illustrative note by the present writer.

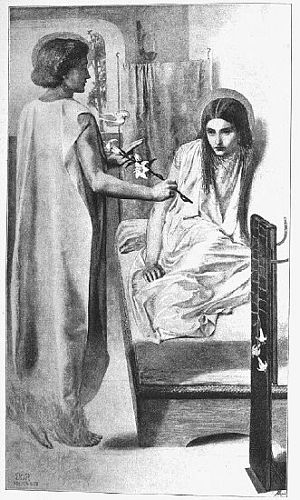

1

On that occasion it was said that this small

picture on panel—it measures only twenty-eight by

sixteen inches—is the one perfect outcome of the

original motive of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

by its representative and typical member. It is not

correct, nor would

Transcribed Footnote (page 19):

1 It was priced at the gallery at £80, and

sold, I believe, to the Marchioness of Bath for that

price. It now belongs to her daughter, the Lady

Louisa Feilding, who lent it, as No. 286, to the

Academy in 1883. There is an amusing note on the

selling of this picture in the

Art Journal,

1884, p. 150.

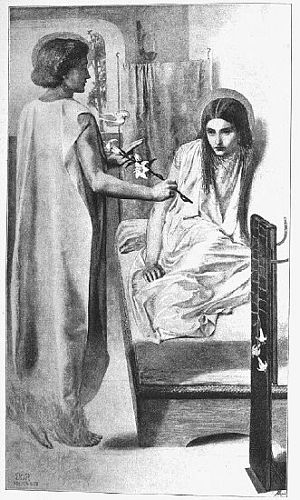

Ecce Ancilla Domini!

Figure: Angel, standing,

presenting a lily to the virgin, who is seated on a bed.

Window frames the angel's head

Note: The fourth complete sentence on page 21 ["A scanty

blue curtain ..."] contains a typographical error: a premature period (.)

following the word "chambers."

it be just to say more of his influence on that much

misrepresented company than admits his leadership

in regard to the pathetic expression of a

religious ideal. Each of the three distinguished

painters whom the world now recognizes (at the

time

Ecce Ancilla Domini!

was in hand

James Collinson had to be reckoned with), so

completely followed his own devices, that after a

year or two, Rossetti was Rossetti alone, and

hardly any traces of his genius are to be found

except on his own canvases. Millais, at least, gave

the painter some help in working out the highly

spiritualised ideal, which may be described as

follows. In a chamber, whose pure white sides and

floor exhibit an intensity of soft morning light, the

couch of Mary, itself almost entirely white, is

placed close to the wall where dawn would strike

its earliest rays, and with its head towards the

window. A scanty blue curtain shaded the face of

the sleeper; behind, attached to the wall, a lamp

(such as in antique chambers. was rarely

extinguished, and supposed efficacious against evil

spirits) is still alight, although it is broad day

without, and the sun reveals the tree growing close

to the opening. At the foot of the couch, Mary's

embroidery frame, with a lily unfinished on the

bright red cloth which was the sole piece of strong

colour in the picture, bespeaks one of those

domestic occupations painters have agreed to

ascribe to the Maiden Mother. As the subjective

incident of the work is the Annunciation, Rossetti

intends us to suppose that the Virgin was aroused

from sleep, if not from prayer, when the gentlest of

the archangels appeared, the light of Heaven filled

the room, and the words “

Ecce Ancilla

Domini!

” were uttered by Mary in submission

to her lot; for it is manifest that

The Girlhood

of Mary, Virgin

, was intended to show her in a

state of mystical pre-cognition, as became the

sequence of the subjects.

How original were the views of Rossetti in

respect to the treatment of this wonderfully

difficult theme will appear when we remember

how other masters had treated it. The Virgins

Annunciate of Angelico, Memmi, Taddeo Bartoli,

Fra Bartolommeo and others, were, as the

Portfolio has already pointed out, generally

handsomely clad, if not crowned and jewelled, and

most of them are enthroned under arched canopies,

adorned with sculptures. The Flemings and

Germans went beyond this, and expended all the

resources of their skill on Mary's

Note: The third complete sentence on page 22 ["It suited

Rossetti's views ..."] contains a typographic error: there is no

final punctuation mark.

brocade, precious stones, goldsmithery, and even

the illuminations of the sumptuous breviary they

bestowed upon her. Rossetti gave her no

ornaments, except the gilded nimbus, which, as in

other pictures, glows round her hair and was

kindled as the angel spoke. She is covered from

head to foot-heel by a simple robe of lawn, leaving

her arms bare, and her dark auburn tresses fall on

her shoulders, and, like the contour of her bust and

limbs, have not the amplitude of womanhood. It

suited Rossetti's views of his subject that the

Virgin, who is almost girlish in her slenderness,

should have but lately passed out of the adolescent

state into a riper one Fra Angelico, whose designs

of the

Rosa

Mystica

are the chastest and

most original of all, witness the lovely

Annunciation of St. Marco's convent and

that other which Sir F. Burton has lately acquired

for the National Gallery, never produced a maiden

more passionless than this; her earnest and

reverent eyes brood, not without knowledge of the

pain to come (a point which had been made of

yore), upon the meaning of Gabriel's salutation;

while awestruck, but not over-powered, she shrinks against the wall, whose whiteness

differentiates the candour of her raiment, and

contrasts with the lustrous aureole of metallic gold

which incloses the dark warmth of her tresses—the

unbound condition of which has, of course, a

meaning all readers recognize in relation to the

Dove which, as in all early pictures of the

Annunciation, descends from above, hovers

towards Mary, and is indicated by the declaration

of the Angelic harbinger. Nearly all the more

ancient pictures of the Italian, German, and Low

Country Schools, not less than cognate sculptured

representations of this subject, give magnificent if

not royal habiliments—sometimes even (as if the

gentle Gabriel were the warlike Michael)

archangelic coronets, armour, and weapons to the

harbinger of Heaven when appearing to Mary. He

is usually winged, and his vast pinions, glittering in

gold, azure and vermilion, and

semée

with stars, reach from his superb tiara to the

floor. A stupendous design by Holbein gives a

Gabriel all glorious to behold, with pinions such as

we seem to hear rustling; while in a voice mighty

but subdued, he, robed like the Kaiser and

grasping the sceptre of his Archangelhood, delivers

his message to a round-eyed and plump Jungfrau

very different from Rossetti's, while the fattest of

doves appears between the imperial angel and the

ponderous maiden. These

figures indicate a motive quite other than that here

in question, in which the stalwart, wingless

harbinger, who is simply clad in white from

radiant head to fiery feet, and holds the lily—an

emblem and a sceptre in one—which it is his duty

to deliver to Mary, approaches her with a calm and

passionless face, which assorts with his noble,

unmoved, and undemonstrative air, as he stands

erect, and—unlike the Gabriels of Angelico,

Memmi, Dürer, Del Sarto, Raphael,

Giovanni Santi, Tintoret and Rembrandt—makes

no obeisance to Mary, not yet crowned Queen of

Heaven. In Tintoret's picture Gabriel rushes into

the stately chamber of the Virgin as if on the wings

of a whirlwind, and a host of angels follow him to

witness the event. There is a second superb design

of Holbein (now in the collection of Mr. Fisher of

Midhurst) in which the grand angel, with a world

of draperies flying in his haste, enters before the

kneeling and tremulous Virgin, while his sword-like

pinions are fully displayed as he grasps a long

sceptre with one hand, and, with the other

extended in a minatory way, speaks as in a voice of

thunder.

This picture was begun and finished in the

squalid Cleveland Street studio. The face of Mary

was a just and true likeness of Rossetti's sister, and

was painted with hardly any alteration of her

features or expression. The face of Gabriel was

mostly founded on that of Woolner, whose hair

supplied the characteristic form and colour of the

archangel's. The nimbus of the archangel is

proper to Rossetti's masterpiece like the other

emblematic lustres of the design, while there is

special significance in the fiery feet of the

Messenger of God. The idea of the Annunciation

as a mystery, thus illustrated by the namesake of

the Harbinger is imperfectly appreciated without

recognition of the character of the fire

streaming from the feet of the Messenger of Peace

as he approached the earth.

While—not without struggles and efforts

innumerable and gallant, for Rossetti's technique

was, in 1849, in a somewhat uncertain and

tentative condition—this picture was in progress,

the

Germ

was concocted and put forth.

The first number of that amazing publication

appeared on “Magazine Day” of December, 1849.

The last number (4) was issued soon after he wrote

on

Ecce

Ancilla Domini!

the date, March, 1850. In this year the picture was No. 225 in the

Portland

Gallery, 316 Regent Street, to which place the

tenants of the Hyde Park Gallery had removed

their exhibition.

Ecce Ancilla Domini!

was

priced in the catalogue at £50. It was

returned unsold and remained on the painter's easel

till January 1853, when Mr. McCracken, a packing

agent of Belfast, who, Mr. W. Rossetti tells us, had

never seen the picture, bought it for the original

price; after his death it changed hands more than

once, including those of Mr. Heugh, with whose

collection it was in 1874 sold; for £388

10

s. it passed to the collection of Mr.

William Graham, who soon after Rossetti's death

lent it to the Academy Winter Exhibition of 1883;

at his sale in 1886 it was bought (price

£840) for the National Gallery out of a fund

bequeathed by the late Mr. John Lucas Walker. It is now No. 1210 in the Gallery.

1

It has been etched not quite successfully by M. Gaujean.

Simultaneously with the execution of

The

Girlhood of Mary, Virgin

, and in the same

dismal Cleveland Street studio above described,

Mr. Holman Hunt painted his famous

Death of

Rienzi's Brother

, which only concerns us here

because, in the rather grotesque (a term I use not

depreciatingly) face of Rienzi vowing to be

revenged on the boy's murderers, we have that

which is by much the truest portrait of D. G.

Rossetti as he appeared at that time. The pallor of

his carnations was exaggerated and made more

adust to suit the passion of the incident; but the

large, dark eyes, strongly marked dark eyebrows,

bold, dome-like forehead, the abundant long and

curling hair falling on each side of the face, and

especially the full red lips conspicuous in the

picture are, or rather were, of Rossetti to the life.

This fine and important painting having

deteriorated in a deplorable manner, has been so

much retouched as to have parted with nine-tenths

of its historical and artistic value.

Not long before it was completed Madox Brown painted a much

less startling version of Rossetti's head in his

Transcribed Footnote (page 24):

1 Here is Rossetti's opinion of his own work as

communicated to Mr. W. Bell Scott in a letter

dated “Kelmscott, June 17th, 1874. My dear

Scotus,—A little early thing of my own,

Annunciation

[this title the painter

preferred for his picture when he sold it to Mr.

McCracken], painted when I was twenty-one—sold

to Agnew at Christie's the other day (to my vast

surprise) for nearly £400. Graham has

since bought it of Agnew, and has sent it to me for

possible revision, but it is best left alone, except

just for a touch or two. Indeed my impression on

seeing it was that I couldn't do quite so well now!”

picture of

Chaucer reading the Legend of

Custance to Edward III.

, and to the present

writer described his doing so in a letter

1

dated November 21st, 1882.

The latter part of the year 1849 was not only

signalised in the manner above stated, but by the

inception of and preparation for the publication of

the

Germ

. With W. M. Rossetti for the

editor the first number comprised of Dante

Rossetti's writing

Songs of Our Household, No.

1

, a poem, and the first version of

Hand and

Soul

, a prose romance in which it is impossible to

avoid recognising the

quasi-nuptial and

deeply devout motives of

The Girlhood of

Mary, Virgin

, and

Ecce Ancilla

Domini!

as they clothed themselves anew in

words. They are both the prototypes of those

legions of poems and novelettes of which the prose

and verse romances of Mr. William Morris are the

most fortunate examples.

2

Note: The first sentence in the second footnote contains a

typographic error: it reads "The Oxford and Cambriage Magazine, ..."

Transcribed Footnote (page 25):

1 Here is part of the letter in question:

“The

Chaucer

was exhibited at the Royal Academy.

50 [No. 380, 1851], at Liverpool,

where it won the £50 prize, in 1859; at my

own exhibition [in 1865, in Pall Mall], and bought

for the public gallery at Sydney, N.S.W. When at

Liverpool it belonged to David Thomas White,

who wished to cut it up (!); so I got it back from

him in exchange for smaller work. Deverell, as you

rightly remember, sat for the page [sitting in front,

an admirable likeness of our dear boy-friend]; W.

M. Rossetti, who then had his hair [

i.e.

previous to his becoming bald], for the troubadour;

John Marshall, the great surgeon, sat for the jester.

I remember his mother's and sister's surprise! D.

G. Rossetti sat for Chaucer himself, and was the

very image of Occleve's little portrait. I began the

head of Chaucer (Rossetti and I both at the top of a

high scaffolding [in a large studio at No. 17

Newman Street, where Rossetti worked under

Brown, as before stated], he reading to me), at 11

P.M., and finished it by 4 A.M. next

morning; when daylight came it looked all right, so I

never touched it again.”

Transcribed Footnote (page 25):

2

The Oxford and Cambridge Magazine

, a

sort of reflection of the

Germ

, published a

few years later, abounds in proofs of Rossetti's

influence on Messrs. Morris and his

entourage. The first number of the

Germ

contained, besides the above, in

“

The

Seasons

”, a lovely lyric by Mr. Coventry

Patmore; Miss Christina Rossetti's versed dirge,

called “

Dream

Land

”, as well as “

An

End

” by the same; a sonnet and a review by her younger

brother; a delightfully fresh “

Sketch from Nature,”

by John L. Tupper, and Woolner's “

My Beautiful

Lady

.” In “

Hand and

Soul

”

it is easy for his

intimates to recognise the outpourings, protests,

and introspective lamentations, the doubts, self-

fears, and partial despair of his future of the author

himself, then struggling with himself to attain

means and powers sufficient for his devotion, his

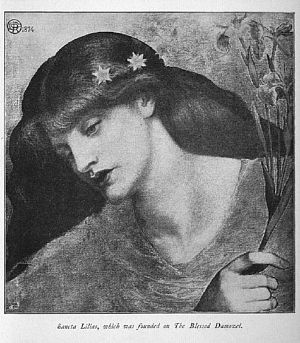

hopes, and his ambition. In No. 2 of the

Germ

we

find the first version of “

The

Blessed Damosel

,” a poem which in after years

supplied a theme and subject for one of Rossetti's

most important pictures. In No. 3 he contributed

“

The

Carillon

,”

one of the fruits of a journey to

Paris and the Low Countries, and “

From the

Cliffs

,” a poem. In No. 4 his contributions were

“

Pax

Vobis

,” and “

Six Sonnets for

Pictures

“ in the Louvre and Luxembourg at Paris,

and in the Academy at Bruges.

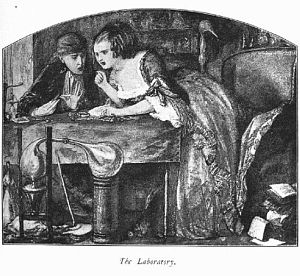

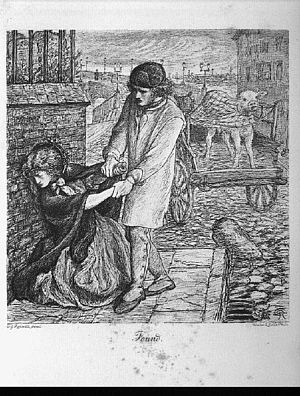

It is time to set forth the prodigious influence

exercised in 1841 and later by the then hardly

recognized poetry of Robert Browning upon

Rossetti and the more imaginative members of that

circle of which he had already become the leader.

This could not be better illustrated than

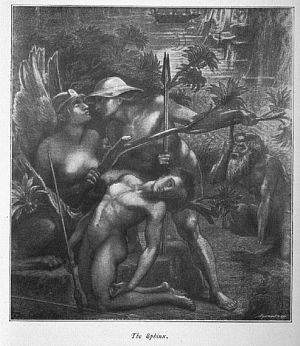

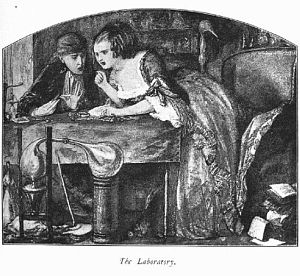

The Laboratory.

Figure: A man and woman lean over a laboratory table. Flasks and burners visible in

foreground.

by the cut which, thanks to the courtesy of Mr.

Fairfax Murray, is now before us and entitled

The Laboratory

,

1

of which the story is that a

Transcribed Footnote (page 26):

1 The subject for this work Rossetti appears to

have found during abundant reading at the British

Museum, which, among other results, led to his

introducing himself to the author of

Paracelsus and

Sordello,

by means

of a letter expressing the highest admiration and

keenest appreciation for that poet's works, then

collected under the title of

Bells and

Pomegranates

. “

The Laboratory originally

appeared in

Hood's

Magazine

in 1844, and

was reprinted in No. VII. of

Bells and

Pomegranates

, 1845, where, no doubt, Rossetti

first met with it and numerous other pieces which

he and all his company took the highest delight in

reading, and in assimilating to their hearts' content

the “scraps of thund'rous epic lilted out” by the

painter-poet. It was with regard to poems of

Browning's that, at the time in view here, Rossetti

chiefly exercised his unrivalled power of reading

aloud and the gigantic resources of his memory.

Nearly all the P-R.B., except perhaps Collinson,

were sympathetic adepts in reading aloud, but none

of them approached Rossetti, whose musical,

modulated, and sonorous voice still rings in the

ears of those who remember with what vigour,

spirit, and poetic appreciation the dear comrade of

those days took his part in reading thus. As to his

memory of poems, that seemed inexhaustible,

when nothing was missed in the recital of a

Lay

of Ancient Rome

, a longish poem of

Tennyson, sections of Henry Taylor's

Philip

van Artevelde

, sequences of a dozen pages

each from

Paracelsus or

Sordello,

passages of Dante and other Italians faultlessly

quoted, and other poetic jewellery borrowed from

Leigh Hunt, Landor, Wordsworth, Chaucer, and

Spenser, and stored in the prodigious mind of the

poet who recited them, and was destined to add to

the wonders of English verse such treasures as

Sister

Helen

,

Jenny

, and

The

Burthen of Nineveh

. All his life Rossetti was

great in reading and reciting aloud, and continued

the practices to the last.

Court-lady of the

ancien

régime

, who had

been jilted, and become maddened by love and

furiously jealous of a fairer rival, visited in his

“devil's smithy” a lean old chemist and

poison-monger like the apothecary in Romeo and

Juliet, and by the gift of all her jewels, nay,

the kisses of her mouth, bribed that gaunt villain to

concoct a “drop.”

When he had finished the dire compound, she

cried to him as in the picture

- Is it done? Take my mask off! Nay, be not morose,

- It kills her, and this prevents seeing it close:

- The delicate droplet, my whole fortune's fee—

- If it hurts her; beside, can it ever hurt me?”

The original of this cut is noteworthy as the first

of Rossetti's completed works in water-colours,

materials which he had not, except tentatively, till

then employed, and because it has such a bold and

original design, and is painted in such brilliant and

strong colours that no one can regard it without surprise.

Apart from the voluptuous suggestiveness—which

was quite new from Rossetti—of the design,

the snake-like virulence of the lady's

face, the deadly passion of her clenched hand, the

eager wrath of her sudden uprising, the lovely

brilliance of her carnations—a little paled by rage

and envy, the sumptuousness of her bust, and the

livid coloration of this striking little work attest the

development of the artist in a way his biographers

have failed to observe, although these

elements are noteworthy in the highest degree.

They mark the opening of his second period,

they excel in movement as in ardour of all kinds,

remind us of Madox Brown, his true master, and,

as it appears to me,

Pages Quarrelling.

Figure: “Two young men facing each other and sparring.”

Surtees p. 220

owe much to what the designer had learnt during

a visit made in the autumn of 1849 to Paris

and the Low Countries, part of the outcome of

which were the

sonnets published in the

Germ

of 1850, that with rare poetic force

and skill commented on several masterpieces of

old art which Rossetti had studied in the Louvre

and at Bruges.

1

The

Laboratory

distinctly reflects the

intense illuminations and pure colour of Memlinc's

and Giorgione's (so-called) pictures at those places,

to which the painter had addressed the sonnets of 1849.

In the early part of the next year, he, by way of

continuing his share in the

Germ

, wrote a

tale of unhappy love intended for the fifth, or April

number thereof, but which never appeared, although

Millais etched his first plate to illustrate

Rossetti's text with the design of a lady dying while

sitting for her portrait. Neither the tale, which was

called

St. Agnes of

Intercession

, nor the

etching was finished, and the latter is now one of the

Transcribed Footnote (page 28):

1 Although it is in many respects the most

important of Rossetti's illustrations to Browning,

The Laboratory

is not the first of them.

Previous to this he had begun in pen and ink a very

elaborate and characteristic illustration to

Pippa

Passes

, in three compartments, the central one

of which, representing

“Hist!” said Kate the

Queen

, seems to have gone astray. The part

particularized was the original of a water-

colour drawing lent by Mrs. Spring Rice, as No. 12, to the

Burlington Club in 1883, and of a portion of an

unfinished picture in oil, called

The Two

Mothers

, which Mr. Hutton lent to the same

exhibition. About 1852 Rossetti drew in ink, and

gave as a keepsake to the present writer,

Taurello's first Sight of

Fortune

, Burlington

Club, No. 21, where it was wrongly dated “C.

1848.” This work derives its origin from

Sordello, and is the sole illustration to that

poem; it was designed to commemorate the giver's

and the receiver's ardent studies anent “Sordello's

delicate spirit all unstrung”.

scarcest of its kind. Rossetti, too, began

an etching to illustrate his own narrative,

but it was soon put aside. It was about this

time, or a little later, that, wanting to

improve his knowledge of perspective, a

subject of the Royal Academy curriculum to

which he had never addressed himself, he came

to me to be helped in that respect. That

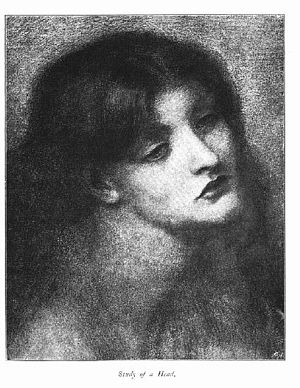

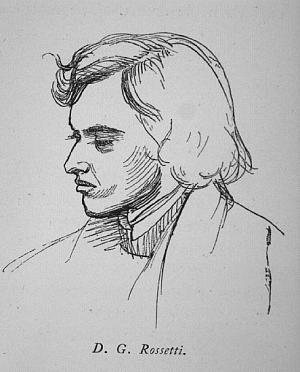

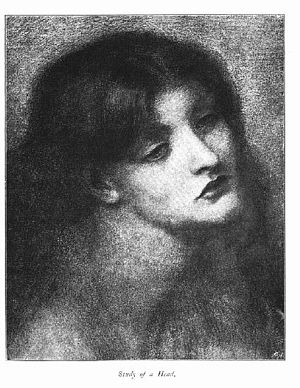

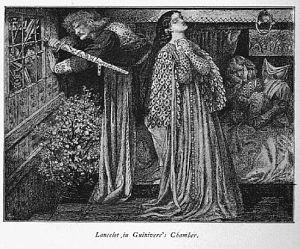

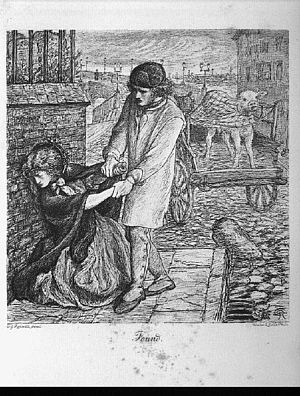

D.G. Rossetti.

Figure: Head and shoulders self-portrait of Rossetti as a young man drawn

in pen and ink, almost in profile to left with eyes downcast.

he was a perfectly intelligent, but not a very

diligent learner is shown by the rough sketch

of two medieval pages quarrelling here

reproduced from among a score of such

remaining on sheets of his exercises in the

little science. Assuming the airs of a

teacher, I had complained that he neglected

his work. His reply was this sketch, intended

to show what I should incur by continuing to

grumble. The oblique lines athwart the feet

of the figures are parts of the diagram.

1

Still later, but of the same period, is

the

profile portrait of

himself

, drawn with a

pen, and here reduced from a sketch which

Rossetti gave to our friend Arthur Hughes,

whose picture of

April

Love

is one

Transcribed Footnote (page 29):

1 Rossetti had so much humour that he cared

little who, if good-naturedly, caricatured

him, and he often sketched himself in odd

circumstances and conditions. One of these

sketches, made in 1849, lies before me now,

and is ludicrously like in all its

exaggerations of a huge head clothed by masses of

dark, unkempt, curling hair, and inclosing gaunt

features, a short beard and moustache,

large, hollow and “detached”-looking

eyes; the head is set upon sloping shoulders

rounded by a slight habitual stoop, and

carried forward in an eager sort of way,

which is true to the life; the chest is

narrow, the hips are wide. The

artist's attire is the above-mentioned

long-tailed dress coat, a loose dress

waistcoat, and loose trousers. The sketch

attests Rossetti's manner of gripping with

his half-clenched fingers the cuff of his

coat—a spasmodic habit which was highly

characteristic of his nervous,

self-concentrated temperament. Much the best

description of Rossetti at this period is Mr.

Holman Hunt's account of himself and “The

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood”, printed in the

Contemporary

Review

, vol. xlix., p.

737; the best portrait of him, apart from the

already-mentioned and somewhat exaggerated

head of Rienzi, is that of the guest, who in

Millais'

Lorenzo and

Isabella

is

drinking from a wine-glass; here the pallor

of the sitter's face is overdone, but the

likeness is otherwise perfect. Mr. W. M.

Rossetti sat for Lorenzo in this picture.

of the most tender-hearted and subtle

love-poems in the world, an idyl of ineffable

pathos and sweetness.

In 1850 Rossetti completed the famous

drawing in ink with a pen, entitled

Hesterna

Rosa

, which illustrates the song, pregnant

of sorrow and shame, of Elena, the mistress of

Philip van Artevelde, in Sir Henry Taylor's

noble drama. The motto of

Hesterna Rosa

is:—

- Quoth tongue of neither maid nor wife

- To heart of neither wife nor maid,

- “Lead we not here a jolly life

- Betwixt the shine and shade?”

- Quoth heart of neither maid nor wife

- To tongue of neither wife nor maid,

- “Thou wag'st, but I am worn with strife,

- And feel like flowers that fade!”

The scene is a tent pitched in a

pleasaunce and, though a pallid dawn gathers

force among the trees, still lit by lamps

from within, so that the gaunt and ghostlike

shadows of a party of revellers seated in

front of the design flicker and start

ominously upon the canvas walls. One gambler

is seated on a couch and throwing dice upon a

stool placed before the group, while his

companion kneels opposite and, with a

goat-like action, draws between his lips the

finger of his mistress, the singer, and

Hesterna Rosa

of the design, who, half

hiding her face with her disengaged hand,

sits behind him. He is waiting the cast of

his companion's dice and will, in turn, throw

his own dice upon the stool. Another girl,

the mistress of the former, sits above him on

the couch, and while she seems to be chanting

a merry, perhaps ribald, song, has thrown her

bare and beautiful arms about his neck. Near

them, on our left, is a young girl holding to

her ear, as if to catch the lowest throbbing

of its notes, a sort of lute, while on the

other side is a huge ape, grossly scratching

himself, and thus intended to repeat the

sensual half of the

motif of the

design, just as the lute-player repeats the

sadder, less degraded pathos of the other

half.

IN 1851 we find Rossetti removed

to a studio on the first floor at No. 72, Newman

Street, and in his art likewise removed from

those hide-binding influences which

inexperience forced upon him in Cleveland

Street. The

Germ

having changed its

name with the third number to

Art and

Poetry

, had come to an end, and with it

the central point, so to say, of our subject's

life had shifted from the religious and

mystical purposes of his first period to

those intensely dramatic and romantic, and

sometimes voluptuous, impulses which

The

Laboratory

heralded and illustrated. The

last-named year produced, besides smaller

examples of less account, a fine and

masculine drawing in ink, now the property of

Mr. Coventry Patmore and called

The

Parable Of Love

, where a lady sits at an

easel painting her own portrait, while her

lover, stooping over her, guides her hand

with his own. The motives and style of this

example, which has never been engraved or

copied, have even more fibre than those of

The Laboratory

. The lover is a

portrait of Woolner. To be grouped with it is

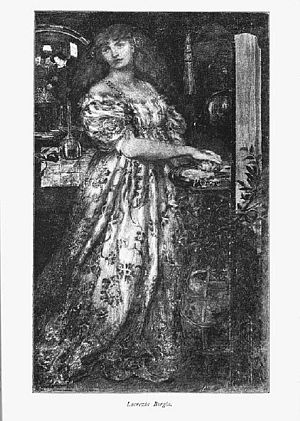

Mr. Boyce's brilliant and powerful drawing in

water colours, called

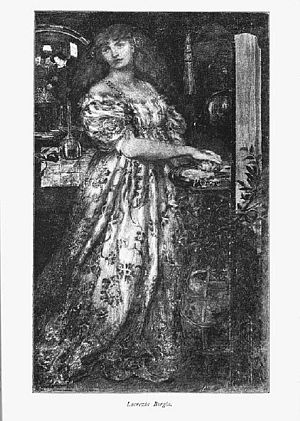

Borgia

, for

which the design in ink dates in 1850. This

little piece measures only 9 1/2 x 10 inches,

but it has that largeness of style we

appreciate highly in an old master, and a

brilliant and powerful coloration as well as

vivid and finely harmonised colours proper,

especially a rich amber and a strong black,

which latter is thus, for the first time,

found in Rossetti's work, and a potent

element in the well conceived chiaroscuro of

the whole. Lucrezia Borgia is seated on a

couch playing on a lute to the sound of which

a boy and a girl are dancing with wonderful

spirit and energy; behind the sumptuously

developed and splendidly clad dame sit the

infamous Pope Alexander VI. and her brother

Cæsar. The latter is blowing the

rose-petals from amid the labyrinth of his

sister's hair,

gazing eagerly at her, and with his dagger

beating time to the music upon a half-filled

wineglass at his side. Belonging to the same

group as

Borgia

, and the property of

the same distinguished water-colour painter

and friend of Rossetti, is the original

drawing in ink with a pen, styled

How they

Met Themselves

, an impressive

illustration of the ancient German legends

anent the

Döppelgänger,

which is here reproduced from one of the two

water-colour versions, painted in 1864. It is

now in the possession of Mr. Pepys Cockerell,

and was developed from the original.

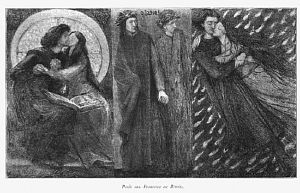

Two lovers are walking in a twilight

wood when they are suddenly confronted by

their own apparitions portending death; she

sinking to the earth, stretches out her arms

as if appealing for mercy, while he, bolder

but overawed, lays his hand upon his sword.

Dramatic as it is, this design is not so

virile and pathetic as the original drawing.

Giotto Painting the

Portrait of Dante

is the most vigorous and apt example of 1852,

and with an extraordinary sense of style and

largeness in design represents the great

Florentine master whom (because of the

majestic simplicity of his motives and

compositions) of all the old painters

Rossetti most affected, sitting on a scaffold

erected before a wall in the Bargello at

Florence and in the act of painting that

likeness of Dante, which, having been

discovered by Mr. Kirkup in 1839, is still

visible there. The austere poet is placed in

a chair, with his knees crossed; he holds a

pomegranate and maintains a dreamy,

self-absorbed expression; Cimabue stands near

Giotto and looks at his fellow painter's

work; Guido Cavalcanti is behind his fellow

poet; below, upon the pavement of the chapel,

we see Beatrice in a procession of

worshippers. This picture is in water colours

and has all the freshness and brightness,

with some of the dryness, of a fresco. The

text of Dante's

Purgatorio, c. xi.

beginning

- Credette Cimabue nella pintura

- Tener lo campo,”—

is most aptly illustrated by this noble

design.

1

Transcribed Footnote (page 32):

1 A sketch for it was shown, a most

exceptional circumstance with regard to a

Rossetti, as No. 7, in a “Winter Exhibition of

Drawings and Sketches at 121 Pall Mall, 1852”;

with it were his

Beatrice meeting Dante at

a Marriage Feast

(196), and

A Sketch

for a Portrait in Venetian Costume

(20).

It appears that Rossetti's offered

contributions to a preceding exhibition of

the same series, which was held in 1851 at

the gallery of the Old Water-Colour Society,

had been, as he said, “kicked out of the

precious place in Pall Mall.”

How they Met themselves.

Figure: “A pair of lovers meet their doubles,

outlined in light, in a wood at twilight—a sure presage of

death.”

Surtees p. 74

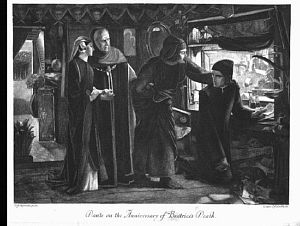

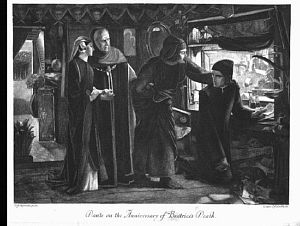

It is certain that prices for Rossetti's

pictures did not at this time “rule

high.” On the contrary we learn that

in April, 1853, Mr. McCracken of Belfast, our

painter's staunch admirer, gave him the sum of

£35 for the masterpiece called

Dante

on the Anniversary of Beatrice's Death

,

of which a plate from the water colour

drawing in the late Mrs. Combe's collection,

recently given to the University of Oxford,

is now before the reader.

The print shows the motives, design,

and composition of the picture, but no

reproduction in black and white can give an

adequate idea of its subtlety, brilliancy,

and colour. The subject was thus quoted by

Rossetti himself from Dante's

Vita

Nuova

, a mine of mystical, introspective

and suggestive matter to which at this time

the painter, more than before or since,

devoted his attention with great energy.

1 His ideal mistress being dead, Dante wrote, “On

that day which completed the year since my

lady had been made [one] of the citizens of

Eternal Life, I was sitting in a place apart,

where, remembering me of her, I was drawing

an angel upon certain tablets, and as I drew,

I turned my eyes and saw beside me persons to

whom it was fitting to do honour, and who

were looking at what I did : and, according as

it was told to me afterwards, they had been

there a while before I perceived them.

Observing whom, I rose for salutation and

said, ‘Another was present with

me.’ ” In the design Dante is

kneeling before a window opening above

the Arno and Florence, and upon

the sill of which stand bottles of pigments

for painting, likewise a significant

pomegranate, while, beneath the sill, lies

with other things the quaint lute alluded to

in the previous note upon “Hesterna

Rosa.” Dante—his attention being

called from his task by the officious friend who

introduced “certain people of importance” his

visitors,—the impression of sorrowful thought still

lingering in his eyes,—turns to look at the

latter, who are an elderly magnate and his

fair, tall and stately daughter. The father's

action indicates that he would fain check the

intrusive action of the busybody, while the

lady, one

Transcribed Footnote (page 34):

1 Browning, too, in his “One Word More, published in

Men and Women,

1855, ii. 229,

sympathetically treated this subject.

Dante on the Anniversary of Beatrice's Death.

D.G. Rossetti, pinx.

Walter L. Colls. Ph. Sc.

Figure: Three visitors stand near the seated Dante, one man clasps his shoulder. Dark

interior highlighted by the bright light shining through the window behind Dante.

Surtees p. 22

of her hands clasping the senior's hand, thus

expresses her sympathy with the sorrow of

Dante and her tender regret that he has been

disturbed. Among the objects within the room

are an hour-glass with its sand more than

half run down, a flowering lily stem, a

convex mirror (the existence of which at this

time is challengeable), a votive picture of

the Virgin and Child, and round the wall, a

row of the heads of cherubs who, like

- “Carvèd angels, ever eager-eyed,

- Stared, where upon their heads the cornice rests,

- With hair blown back, and wings put cross-wise on their

breasts.”

Outside the chamber and beyond the

half-withdrawn

portière we see a

closet with a brass cistern suspended over

a basin for washing hands, one of those quite

“impracticable”

staircases which, as with his musical

instruments, were the despair of the

specialists, and, farther off, a serene