Rossetti Archive Textual Transcription

The full Rossetti Archive record for this transcribed document is available.

OF

DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI

D. G. Rossetti

From a Photograph by Downey 1862

OF

DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI

EDITED

WITH PREFACE AND NOTES

BY

WILLIAM M. ROSSETTI

REVISED AND ENLARGED EDITION

LONDON

ELLIS: 29 New Bond Street, W.

1911

PRINTED AND BOUND BY

HAZELL, WATSON AND VINEY, LD

LONDON AND AYLESBURY.

DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI

DIED 9 APRIL 1882 AGED 53

FRANCES MARY LAVINIA ROSSETTI

DIED 8 APRIL 1886 AGED 85

TO

THE MOTHER'S SACRED MEMORY

THIS COLLECTED EDITION OF

THE SON'S WORKS

IS DEDICATED BY

THE SURVIVING SON AND BROTHER

W M R

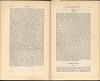

of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, as of most authors, would probably

be to offer a broad general view of his writings, and to analyse

with some critical precision his relation to other writers,

contemporary or otherwise, and the merits and defects of his

performances. In this case, as in how few others, one would

also have to consider in what degree his mind worked con-

sentaneously or diversely in two several arts—the art of poetry

and the art of painting. But the hand of a brother is not

the fittest to undertake any work of this scope. My preface

will not therefore deal with themes such as these, but will

be confined to minor matters, which may nevertheless be

relevant also within their limits. And first may come a very

brief outline of the few events of an outwardly uneventful

life.

his professional career, modified his name into Dante Gabriel

Rossetti, was born on 12th May 1828, at No. 38 Charlotte

Street (now 110 Hallam Street), Portland Place, London.

In blood he was three-fourths Italian, and only one-fourth

English; being on the father's side wholly Italian (Abruzzese),

and on the mother's side half Italian (Tuscan) and half

English. His father was Gabriele Rossetti, born in 1783 at

Vasto, in the Abruzzi, Adriatic coast, in the then kingdom

of Naples. Gabriele Rossetti (died 1854) was a man of letters,

a custodian of ancient bronzes in the Museo Borbonico of

Naples, and a poet; he distinguished himself by patriotic

lays which fostered the popular movement resulting in the

grant of a constitution by Ferdinand I. of Naples in 1820.

The King, after the fashion of Bourbons and tyrants, revoked

the constitution in 1821, and persecuted the abettors of it,

and Rossetti had to escape for his freedom, or perhaps even

for his life. He settled in London in 1824, married, and

became Professor of Italian in King's College, London,

publishing also various works of bold speculation in the way

of Dantesque commentary and exposition. His wife was

Frances Mary Lavinia Polidori (died 1886), daughter of

Gaetano Polidori (died 1853), a teacher of Italian and literary

man who had in early youth been secretary to the poet

Alfieri, and who published various books, including a com-

plete translation of Milton's poems. Frances Polidori was

English on the side of her mother, whose maiden name was

Pierce. The family of Rossetti and his wife consisted of four

children, born in four successive years—Maria Francesca

(died 1876), Dante Gabriel, William Michael, and Christina

Georgina (died 1894). Few more affectionate husbands and

fathers have lived, and no better wife and mother, than

Gabriele and Frances Rossetti. The means of the family

were always strictly moderate, and became scanty towards

1843, when the father's health began to fail. In 1842 (or

perhaps 1841) Dante Gabriel left King's College School, where

he had learned Latin, French, and a beginning of Greek;

and he entered upon the study of the art of painting, to

which he had from earliest childhood exhibited a very marked

bent. After a while he was admitted to the school of the

Royal Academy, but never proceeded beyond its antique

section. In 1848 Rossetti co-operated with two of his fellow-

students in painting, John Everett Millais and William Hol-

man Hunt, and with the sculptor Thomas Woolner, in form-

ing the so-called Præraphaelite Brotherhood. There were

three other members of the Brotherhood—James Collinson,

Frederic George Stephens, and the present writer. Ford

Madox Brown, the historical painter, was known to Rossetti

a little before the Præraphaelite scheme was started, and

bore an important part both in directing his studies and in

upholding the movement, but he did not think fit to join

the Brotherhood in any direct or complete sense. Through

a fellow-painter, Walter Howell Deverell, Rossetti came to

know Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal, daughter of a Sheffield cutler,

herself a milliner's assistant, gifted with some artistic and

some poetic faculty: in the Spring of 1860, after a long

engagement, they married. Their wedded life was of short

duration, as she died in February 1862, having meanwhile

given birth to a still-born child. For several years up to this

date Rossetti, designing and painting many works, in oil-

colour or as yet more frequently in water-colour, had resided

at No. 14 Chatham Place, Blackfriars Bridge, a line of street

now demolished. In the autumn of 1862 he removed to

No. 16 Cheyne Walk, Chelsea. At first certain apartments in

the house were occupied by Mr. George Meredith the novelist,

Mr. Swinburne the poet, and myself. This arrangement did

not last long, although I myself remained a partial inmate of

the house up to 1873. My brother continued domiciled in

Cheyne Walk until his death; but from 1871 he was some-

times away at Kelmscot manorhouse, in Oxfordshire, not far

from Lechlade, occupied jointly by himself, and by the poet

Mr. William Morris with his family. From the autumn of

1872 till the summer of 1874 he was wholly settled at

Kelmscot, scarcely visiting London at all. He then returned

to London, and Kelmscot passed out of his ken.

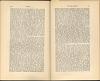

lite Brotherhood, with the co-operation of some friends,

brought out a short-lived magazine named The Germ (after-

wards Art and Poetry); here appeared the first verses and

the first prose published by Rossetti, including The Blessed

Damozel and Hand and Soul . In 1856 he contributed a little

to The Oxford and Cambridge Magazine , printing there The

Burden of Nineveh and Staff and Scrip. In 1861, during his

married life, he published his volume of translations The

Early Italian Poets , now entitled Dante and his Circle . By

the time therefore of the death of his wife he had a certain

restricted yet far from inconsiderable reputation as a poet,

along with his recognized position as a painter—a non-

exhibiting painter, for, after the first two or three years of

his professional course, he adhered with practical uniformity

to the plan of abstaining from exhibition altogether. He

had contemplated bringing out in or about 1862 a volume of

original poems; but, in the grief and dismay which over-

whelmed him in losing his wife, he determined to sacrifice to

her memory this long-cherished project, and he buried in

her coffin the manuscripts which would have furnished forth

the volume. With the lapse of years he came to see that,

as a final settlement of the matter, this was neither obligatory

nor desirable; so in 1869 the manuscripts were disinterred,

and in 1870 his volume named Poems was issued. For some

considerable while it was hailed with general and lofty praise,

chequered by only moderate stricture or demur; but late

in 1871 Mr. Robert Buchanan published under a pseudonym,

in the Contemporary Review , a very hostile article named

The Fleshly School of Poetry , attacking the poems on literary

and more especially on moral grounds. The article, in an

enlarged form, was afterwards reissued as a pamphlet. The

assault produced on Rossetti an effect altogether dispropor-

tionate to its intrinsic importance; indeed, it developed in

his character an excess of sensitiveness and of distempered

brooding which his nearest relatives and friends had never

before surmised,—for hitherto he had on the whole had an

ample sufficiency of high spirits, combined with a certain

underlying gloominess or abrupt moodiness of nature and out-

look. Unfortunately there was in him already only too much

of morbid material on which this venom of detraction was

to work. For some years the state of his eyesight had given

very grave cause for apprehension, he himself fancying from

time to time that the evil might end in absolute blindness, a

fate with which our father had been formidably threatened

in his closing years. From this or other causes insomnia had

ensued, coped with by far too free a use of chloral, which may

have begun towards the spring of 1870. In the summer of

1872 he had a dangerous crisis of illness; and from that

time forward, but more especially from the middle of 1874,

he became secluded in his habits of life, and often depressed,

fanciful, and gloomy. Not indeed that there were no in-

tervals of serenity, even of brightness; for in fact he was

often genial and pleasant, and a most agreeable companion

with as much bonhomie as acuteness for wiling an evening

away. He continued also to prosecute his pictorial work

with ardour and diligence, and at times he added to his

product as a poet. The second of his original volumes,

Ballads and Sonnets , was published in the autumn of 1881.

About the same time he sought change of air and scene in

the Vale of St. John, near Keswick, Cumberland; but he

returned to town more shattered in health and in mental tone

than he had ever been before. In December a shock of a

quasi-paralytic character struck him down. He rallied

sufficiently to remove to Birchington-on-Sea, near Margate.

The hand of death was then upon him, and was to be relaxed

no more. The last stage of his maladies was uræmia. Tended

by his mother and his sister Christina, with the constant

companionship at Birchington of Mr. Hall Caine, and in the

presence likewise of Mr. Theodore Watts-Dunton, Mr.

Frederic Shields, and myself, he died on Easter Sunday,

April 9th 1882. His sister-in-law, the daughter of Madox

Brown, arrived immediately after his latest breath had been

drawn. He lies buried in the churchyard of Birchington.

one another's feelings and thoughts more intimately, in child-

hood, boyhood, and well on into mature manhood, than

Dante Gabriel and myself. I have no idea of limning his

character here at any length, but will define a few of its

leading traits. He was always and essentially of a dominant

turn, in intellect and in temperament a leader. He was im-

petuous and vehement, and necessarily therefore impatient;

easily angered, easily appeased, although the embittered

feelings of his later years obscured this amiable quality to

some extent; constant and helpful as a friend where he per-

ceived constancy to be reciprocated; free-handed and heed-

less of expenditure, whether for himself or for others; in

family affection warm and equable, and (except in relation

to our mother, for whom he had a fondling love) not demon-

strative. Never on stilts in matters of the intellect or of

aspiration, but steeped in the sense of beauty, and loving,

if not always practising, the good; keenly alive also to the

laughable as well as the grave or solemn side of things;

superstitious in grain, and anti-scientific to the marrow.

Throughout his youth and early manhood I considered him

to be markedly free from vanity, though certainly well

equipped in pride; the distinction between these two ten-

dencies was less definite in his closing years. Extremely

natural and therefore totally unaffected in tone and manner,

with the naturalism characteristic of Italian blood; good-

natured and hearty, without being complaisant or accommo-

dating; reserved at times, yet not haughty; desultory enough

in youth, diligent and persistent in maturity; self-centred

always, and brushing aside whatever traversed his purpose

or his bent. He was very generally and very greatly liked

by persons of extremely diverse character; indeed, I think

it can be no exaggeration to say that no one ever disliked

him. Of course I do not here confound the question of liking

a man's personality with that of approving his conduct out-

and-out.

I have said that it was natural; it was likewise eminently

easy, and even of the free-and-easy kind. There was a

certain British bluffness, streaking the finely poised Italian

suppleness and facility. As he was thoroughly unconven-

tional, caring not at all to fall in with the humours or pre-

possessions of any particular class of society, or to conciliate

or approximate the socially distinguished, there was little in

him of any veneer or varnish of elegance; none the less he

was courteous and well-bred, meeting all sorts of persons

upon equal terms— i.e., upon his own terms; and I am

satisfied that those who are most exacting in such matters

found in Rossetti nothing to derogate from the standard of

their requirements. In habit of body he was indolent and

lounging, disinclined to any prescribed or trying exertion of

any sort, and very difficult to stir out of his ordinary groove,

yet not wanting in active promptitude whenever it suited

his liking. He often seemed totally unoccupied, especially

of an evening; no doubt the brain was busy enough.

than English, though I have more than once heard it said

that there was nothing observable to bespeak foreign blood.

He was of rather low middle stature, say five feet seven and

a half, like our father; and, as the years advanced, he re-

sembled our father not a little in a characteristic way, yet

with highly obvious divergences. Meagre in youth, he was

at times decidedly fat in mature age. The complexion, clear

and warm, was also dark, but not dusky or sombre. The

hair was dark and somewhat silky; the brow grandly spacious

and solid; the full-sized eyes blueish-grey; the nose shapely,

decided, and rather projecting, with an aquiline tendency

and large nostrils, and perhaps no detail in the face was more

noticeable at a first glance than the very strong indentation

at the spring of the nose below the forehead; the mouth

moderately well-shaped, but with a rather thick and un-

moulded under-lip; the chin unremarkable; the line of the

jaw, after youth was passed, full, rounded, and sweeping; the

ears well-formed and rather small than large. His lips were

wide, his hands and feet small; the hands very much those

of the artist or author type, white, delicate, plump, and soft

as a woman's. His gait was resolute and rapid, his general

aspect compact and determined, the prevailing expression of

the face that of a fiery and dictatorial mind concentrated

into repose. Some people regarded Rossetti as eminently

handsome; few, I think, would have refused him the epithet

of well-looking. It rather surprises me to find from Mr.

Caine's book of Recollections that that gentleman, when he

first saw Rossetti in 1880, considered him to look full ten

years older than he really was,—namely, to look as if sixty-

two years old. To my own eye nothing of the sort was

apparent. He wore moustaches from early youth, shaving his

cheeks; from 1873 or thereabouts he grew whiskers and beard,

moderately full and auburn-tinted, as well as moustaches.

His voice was deep and harmonious; in the reading of poetry,

remarkably rich, with rolling swell and musical cadence.

the interruption of his ordinary habits of life, and the flurry

or discomfort, involved in locomotion; moreover, he was a

bad sailor. In boyhood he knew Boulogne: he was in Paris

three or four times, and twice visited some principal cities

of Belgium. This was the whole extent of his foreign travel-

ling. He crossed the Scottish border more than once and

knew various parts of England pretty well—Hastings, Bath,

Oxford, Matlock, Stratford-on-Avon, Newcastle-on-Tyne,

Bognor, Herne Bay; Kelmscot, Keswick, and Birchington-

on-Sea have been already mentioned. From 1878 or there-

abouts he became, until he went to the neighbourhood of

Keswick, an absolute home-keeping recluse, never even

straying outside the large garden of his own house, except to

visit from time to time our mother in the central part of

London.

and could always have commanded any amount of inter-

course with any number of ardent or kindly well-wishers, had

he but felt elasticity or cheerfulness of mind enough for the

purpose. I should do injustice to my own feelings if I were

not to mention here some of his leading friends. First and

foremost I name Mr. Madox Brown, his chief intimate through-

out life, on the unexhausted resources of whose affection and

converse he drew incessantly for long years; they were at

last separated by the removal of Mr. Brown to Manchester,

for the purpose of painting the Town Hall frescoes. The

Præraphaelites—Millais, Hunt, Woolner, Stephens, Collinson

—were on terms of unbounded familiarity with him in youth;

owing to death or other causes, he lost sight eventually of all

of them except Mr. Stephens. Mr. William Bell Scott was,

like Mr. Brown, a close friend from a very early period until

the last; Scott being both poet and painter, there was a

strict bond of affinity between him and Rossetti. Mr. Ruskin

was extremely intimate with my brother from 1854 till about

1865, and was of material help to his professional career.

As he rose towards celebrity, Rossetti knew Burne Jones,

and through him Morris and Swinburne, all staunch and

fervently sympathetic friends. Mr. Shields was a rather later

acquaintance, who soon became an intimate, equally re-

spected and cherished. Then Mr. Hueffer the musical critic

(afterwards a close family connection, editor of the Tauchnitz

edition of Rossetti's works), and Dr. Hake the poet. Through

the latter my brother came to know Mr. Theodore Watts-

Dunton, whose intellectual companionship and incessant

assiduity of friendship did more than anything else towards

assuaging the discomforts and depression of his closing years.

In the latest period the most intimate among new acquaint-

ances were Mr. William Sharp and Mr. Hall Caine, both of

them known to Rossettian readers as his biographers. Nor

should I omit to speak of the extremely friendly relation in

which my brother stood to some of the principal purchasers

of his pictures—Mr. Leathart, Mr. Rae, Mr. Leyland, Mr.

Graham, Mr. Valpy, Mr. Turner, and his early associate Mr.

Boyce. Other names crowd upon me—James Hannay, John

Tupper, Patmore, Thomas and John Seddon, Mrs. Bodichon,

Browning, John Marshall, Tebbs, Mrs. Gilchrist, Miss Boyd,

Sandys, Whistler, Joseph Knight, Fairfax Murray, Mr. and

Mrs. Stillman, Treffry Dunn, Lord and Lady Mount-Temple,

Oliver Madox Brown, the Marstons, father and son—but I

forbear.

etc. of my brother's writings, it may be worth while to speak

of the poets who were particularly influential in nurturing

his mind and educing its own poetic endowment. The first

poet with whom he became partially familiar was Shakespear.

Then followed the usual boyish fancies for Walter Scott and

Byron. The Bible was deeply impressive to him, perhaps

above all Job, Ecclesiastes, and the Apocalypse. Byron gave

place to Shelley when my brother was about sixteen years

of age; and Mrs. Browning and the old English or Scottish

ballads rapidly ensued. It may have been towards this

date, say 1845, that he first seriously applied himself to

Dante, and drank deep of that inexhaustible well-head of

poesy and thought; for the Florentine, though familiar to

him as a name, and in some sense as a pervading penetrative

influence, from earliest childhood, was not really assimilated

until boyhood was practically past. Bailey's Festus was

enormously relished about the same time—read again and

yet again; also Faust, Victor Hugo, Alfred de Musset (and

along with them a swarm of French novelists), and Keats,

whom my brother for the most part, though not without

some compunctious visitings now and then, truly preferred

to Shelley. The only classical poet whom he took to in any

degree worth speaking of was Homer, the Odyssey consider-

ably more than the Iliad. Tennyson reigned along with

Keats, and Edgar Poe and Coleridge along with Tennyson.

In the long run he perhaps enjoyed and revered Coleridge

beyond any other modern poet whatsoever; but Coleridge

was not so distinctly or separately in the ascendant, at any

particular period of youth, as several of the others. Blake

likewise had his peculiar meed of homage, and Charles Wells,

the influence of whose prose style, in the Stories after Nature,

I trace to some extent in Rossetti's Hand and Soul . Lastly

came Browning, and for a time, like the serpent-rod of Moses,

swallowed up all the rest. This was still at an early stage

of life; for I think the year 1847 cannot certainly have been

passed before my brother was deep in Browning. The

readings or fragmentary recitations of Bells and Pomegranates,

Paracelsus, and above all Sordello, are something to remember

from a now distant past. My brother lighted upon Pauline

(published anonymously) in the British Museum, copied it

out, recognized that it must be Browning's, and wrote to the

great poet at a venture to say so, receiving a cordial response,

followed by a genial and friendly intercourse for several

years. One prose-work of great influence upon my brother's

mind, and upon his product as a painter, must not be left

unspecified—Malory's Mort d'Arthur, which he knew to some

extent in boyhood, and which engrossed him towards 1856.

The only poet whom I feel it needful to add to the above is

Chatterton. In the last two or three years of his life my

brother entertained an abnormal—I think an exaggerated—

admiration of Chatterton. It appears to me that (to use a

very hackneyed phrase) he “evolved this from his inner

consciousness” at that late period; certainly in youth and

early manhood he had no such feeling. He then read the

poems of Chatterton with cursory glance and unexcited

spirit, recognizing them as very singular performances for

their date in English literature, and for the author's boyish

years, but beyond that laying no marked stress upon them.

unmentioned in this list: I have stated the facts as I re-

member and know them. Chaucer, Spenser, the Elizabethan

dramatists (other than Shakespear), Milton, Dryden, Pope,

Wordsworth, are unnamed. It should not be supposed that

he read them not at all, or cared not for any of them; but,

if we except Chaucer in a rather loose way and (at a late

period of life) Marlowe in some of his non-dramatic poems,

they were comparatively neglected. Thomas Hood he valued

highly; also very highly Burns in mature years, but he was

not a constant reader of the Scottish lyrist. Of Italian poets

he earnestly loved none save Dante: Cavalcanti in his degree,

and also Poliziano and Michelangelo—not Petrarca, Boccaccio,

Ariosto, Tasso, or Leopardi, though in boyhood he delighted

well enough in Ariosto. Of French poets, none beyond

Hugo and Alfred de Musset; except Villon, and partially

Dumas, whose novels ranked among his favourite reading.

In German poetry he read nothing currently in the original,

although (as our pages bear witness) he had in earliest youth

so far mastered the language as to make some translations.

Calderon, in Fitzgerald's version, he admired deeply; but

this was only at a late date. He had no liking for the

specialities of Scandinavian, nor indeed of Teutonic, thought

and work, and little or no curiosity about Oriental—such as

Indian, Persian, or Arabic—poetry. Any writing about

devils, spectres, or the supernatural generally, whether in

poetry or in prose, had always a fascination for him; at one

time, say 1844, his supreme delight was the blood-curdling

romance of Maturin, Melmoth the Wanderer.

Of his merely childish or boyish performances I need have

said nothing, were it not that they have been mentioned in

other books regarding Rossetti. First then there was The

Slave , a “drama” which he composed and wrote out in or

about the seventh year of his age. It is of course simple

nonsense. “Slave” and “traitor” were two words which

he found passim in Shakespear; so he gave to his principal

characters the names of Slave and Traitor. If what they do

is meaningless, what they say (when they deviate from

prose) is not exactly unmetrical. Towards his thirteenth

year he began a romantic prose-tale named Roderick and

Rosalba . I hardly think that he composed anything else

prior to the ballad narrative Sir Hugh the Heron , founded on

a tale by Allan Cunningham. Our grandfather printed it

in 1843, which is some couple of years after the date of its

composition. It is correctly enough versified, but has no

merit, and little that could even be called promise. Soon

afterwards a prose-tale named Sorrentino , in which the devil

played a conspicuous part, was begun, and carried to some

length; it was of course boyish, but it must, I think, have

shown some considerable degree of cleverness. In 1844 there

was the translation of Bürger's Lenore , spirited and fairly

efficient; and in November 1845 was begun a translation of

the Nibelungenlied , almost deserving (if my memory serves me)

to be considered good. Several hundred lines of it must

certainly have been written. My brother was by this time

a practised and competent versifier, at any rate, and his

mere prentice-work may count as finished.

along with the version of Der Arme Heinrich , and the begin-

ning of his translations from the early Italians. These must,

I think, have been in full career in the first half of 1847, and

may even have begun in 1845. They show a keen sensitive-

ness to whatsoever is poetic in the originals, and a sinuous

strength and ease in providing English equivalents, with the

command of a rich and romantic vocabulary. In his nine-

teenth year, or before 12th May 1847, he wrote The Blessed

Damozel . As that is universally recognized as one of his

typical or consummate productions, marking the high level

of his faculty whether inventive or executive, I may here

close this record of preliminaries; the poems, with such

slight elucidations as my notes supply, being left to speak

for themselves. I will only add that for some while, more

especially in the latter part of 1848 and in 1849, my brother

practised his pen to no small extent in writing sonnets to

bouts-rimés. He and I would sit together in our bare little

room at the top of No. 50 Charlotte Street, I giving him the

rhymes for a sonnet, and he me the rhymes for another;

and we would write off our emulous exercises with consider-

able speed, he constantly the more rapid of the two. From

five to eight minutes may have been the average time for

one of his sonnets; not unfrequently more, and sometimes

hardly so much. In fact, the pen scribbled away at its

fastest. Several of his bouts-rimés sonnets still exist in

my possession, a little touched up after the first draft: I

present most of them in this re-edition. Some have a faux

air of intensity of meaning, as well as of expression; but

their real core of significance is necessarily small, the only

wonder being how he could spin so deftly with so weak a

thread. I may be allowed to mention that most of my own

sonnets (and not sonnets alone) published in The Germ were

bouts-rimés experiments such as above described. In poetic

tone they are of course inferior to my brother's work of like

fashioning; in point of sequence or self-congruity of mean-

ing, the comparison might be less to my disadvantage.

volumes, chiefly of poetry. I shall transcribe the title-pages

verbatim.

Dante Alighieri (1100—1200—1300) in the Original Metres.

Together with Dante's Vita Nuova. Translated by D. G.

Rossetti. Part I. Poets chiefly before Dante. Part II.

Dante and his Circle. London: Smith, Elder and Co.

65, Cornhill. 1861. The rights of translation and reproduc-

tion, as regards all editorial parts of this work, are reserved.

him (1100—1200—1300). A Collection of Lyrics, edited,

and translated in the original metres, by Dante Gabriel

Rossetti. Revised and rearranged edition. Part I. Dante's

Vita Nuova, &c. Poets of Dante's Circle. Part II. Poets

chiefly before Dante. London: Ellis and White, 29, New

Bond Street. 1874.

Ellis, 33, King Street, Covent Garden. 1870.

London: Ellis and White, 29, New Bond Street. 1881.

London: Ellis and White, 29, New Bond Street, W. 1881.

book as 1 a, but altered in arrangement, chiefly by inverting

the order in which the poems of Dante and of the Dantesque

epoch, and those of an earlier period, are printed. In the

present collection, I reprint 1 b, taking no further count of 1 a.

The volume 2 b is to a great extent the same as 2 a, yet by

no means identical with it. 2 a contained a section named

Sonnets and Songs, towards a work to be called “The House

of Life.” In 1881, when 2 b and 3 were published simul-

taneously, The House of Life was completed, was made to

consist solely of sonnets, and was transferred to 3; while the

gap thus left in 2 b was filled up by other poems. This essential

modification of The House of Life clearly governed my action.

question had to be considered whether I should reprint 2 b and

3 exactly as they stood in 1881, adding after them a section

of poems not hitherto printed in any one of my brother's

volumes; or whether I should recast, in point of arrange-

ment, the entire contents of 2 b and 3, inserting here and

there, in their most appropriate sequence, the poems hitherto

unprinted. I have chosen the latter alternative, as being

in my own opinion the only arrangement which is thoroughly

befitting for an edition of Collected Works. I am aware that

some readers would have preferred to see the old order— i.e.,

the order of 1881—retained, so that the two volumes of that

year could be perused as they then stood. Indeed, one of

my brother's friends, most worthy, whether as friend or as

critic, to be consulted on such a subject, decidedly advocated

that plan. On the other hand, I found my own view con-

firmed by my sister Christina, who, both as a member of the

family and as a poetess, deserved an attentive hearing. The

reader who inspects my table of contents will be readily able

to follow the method of arrangement which is here adopted.

I have divided the materials into Principal Poems, Miscel-

laneous Poems, Translations, and some minor headings; and

have in each section arranged the poems—and the same has

been done with the prose-writings—in the order of the dates

of their composition. This order of date is certainly near to

being correct; though some allowance, especially in the case

of The House of Life , must be made for differences of period

when the poems were begun and were brought into their final

form. The few translations which were printed in 2 b (as

also in 2 a) have been removed to follow on after 1 b.

to include among his Collected Works. One of these is a

grotesque ballad about a Dutchman, Jan van Hunks , begun

at a very early date, and finished in his last illness. The

other is a brace of sonnets, interesting in subject, and as

being the very latest thing that he wrote. These works were

presented as a gift of love and gratitude to Mr. Watts-Dunton,

with whom it remains to publish them at his own discretion:

he has already brought out Jan van Hunks in The English

Review .

add, a very fastidious painter. He did not indeed “cudgel

his brains” for the idea of a poem or the structure or diction

of a stanza. He wrote out of a large fund or reserve of

thought and consideration, which would culminate in a clear

impulse or (as we say) an inspiration. In the execution he

was always heedful and reflective from the first, and he

spared no after-pains in clarifying and perfecting. He ab-

horred anything straggling, slipshod, profuse, or uncondensed.

He often recurred to his old poems, and was reluctant to

leave them merely as they were. A natural concomitant

of this state of mind was a great repugnance to the notion of

publishing, or of having published after his death, whatever

he regarded as juvenile, petty, or inadequate. As editor of

his Collected Works, I have had to regulate myself to a large

extent by these feelings of his, whether my own entirely

correspond with them or not. The amount of unpublished

work which he left behind him was by no means large; out

of the moderate bulk I have been careful to select only such

examples as I suppose that he would himself have approved

for the purpose, or would, at any rate, not gravely have

objected to. A few, which he might have objected to, figure

as Juvenilia. Some details regarding the new items will be

found among my notes. Some projects or arguments of

poems which he never executed are also printed among his

prose-writings. These particular projects had, I think, been

practically abandoned by him in all the later years of his

life; but there was one subject which he had seriously at

heart, and for which he had collected some materials, and he

would perhaps have put it into shape had he lived a year or

two longer—a ballad on the subject of Joan of Arc to match

The White Ship and The King's Tragedy .

considered himself more essentially a poet than a painter.

To vary the form of expression, he thought that he had

mastered the means of embodying poetical conceptions in the

verbal and rhythmical vehicle more thoroughly than in form

and design, perhaps more thoroughly than in colour.

London, April 1911.

2 b, and 3. The dedication to 1 b appears in its proper place.

D.G.R. 1861.

which, so many years back, he gave the first brotherly hearing,

are now at last dedicated.

these few more pages are affectionately inscribed.

ment”:

“‘Many poems in this volume were written

between 1847 and

1853. Others are of recent date, and a few belong

to the inter-

vening period. It has been thought unnecessary to

specify the

earlier work, as nothing is included which the author

believes to

be immature.’

“The above brief note was prefixed to these poems when

first

published in 1870. They have now been for some time out

of

print.

“The fifty sonnets of

The House of Life

, which first appeared

here, are now embodied with the full

series in the volume entitled

Ballads and Sonnets

.

“The fragment of

The Bride's Prelude

, now first printed, was

written very early, and is here

associated with other work of the

same date; though its publication

in an unfinished form needs

some indulgence.”

those marked † have appeared in print before, but are now first in-

cluded in the Collected Works.

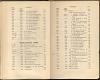

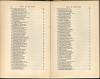

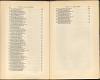

- Preface by Wm. M. Rossetti . . . . . vii

-

-

PRINCIPAL POEMS

- 1847 . . 1850 The Blessed Damozel . . 3

- 1848-50 also

1869-70 . } 1870 Dante at Verona . . .6 - 1848, also

1859, etc. } 1881 The Bride's Prelude . . 17 - 1848, mostly

1858-69 } 1870 Jenny . . . . 36 - 1849, also

1869-70 } 1870 A Last Confession . . . 44 - 1850 and

later } 1856 The Burden of Nineveh . . 55 - 1851-2 . 1856 The Staff and Scrip . . 59

- 1851, also

1880 } 1854 Sister Helen . . . 64 - 1854 . . 1870 Love's Nocturn . . . 70

- 1847-81 . 1863-81

THE HOUSE OF LIFE:

A Sonnet-Sequence: - 1880 . . 1881 Introductory Sonnet . . 74

-

-

Part I.—Youth and

Change

:

- 1871 . . 1881 1. Love Enthroned . . 74

- 1869 . . 1870 2. Bridal Birth . . 75

- 1869 . . 1870 3. Love's Testament . . 75

- 1869 . . 1870 4. Lovesight . . 75

- 1871 . . 1881 5. Heart's Hope . . 76

- 1869 . . 1870 6. The Kiss . . 76

- 1869 . . 1870 †6a. Nuptial Sleep. . 76

- 1870 . . 1870 7. Supreme Surrender . 77

- 1869 . . 1881 8. Love's Lovers . . 77

- 1870 . . 1870 9. Passion and Worship . 77

- 1868 . . 1870 10. The Portrait . . 78

- 1870 . . 1870 11. The Love-letter . . 78

- 1871 . . 1881 12. The Lovers' Walk . . 78

- 1871 . . 1881 13. Youth's Antiphony . . 79

- 1870 . . 1881 14. Youth's Spring-tribute . 79

- 1854 . . 1870 15. The Birth-bond . . 79

- 1870 . . 1870 16. A Day of Love . . 80

- 1871 . . 1881 17. Beauty's Pageant . . 80

- 1871 . . 1881 18. Genius in Beauty . . 80

- 1871 . . 1881 19. Silent Noon . . . 81

- 1871 . . 1881 20. Gracious Moonlight . . 81

- 1870 . . 1870 21. Love-sweetness . . 81

- 1871 . . 1881 22. Heart's Haven . . 82

- 1870 . . 1870 23. Love's Baubles . . 82

- 1871 . . 1881 24. Pride of Youth . . 82

- 1869 . . 1869 25. Winged Hours . . 83

- 1871 . . 1881 26. Mid-rapture . . 83

- 1871 . . 1881 27. Heart's Compass . . 83

- 1871 . . 1881 28. Soul-light . . . 84

- 1871 . . 1881 29. The Moonstar . . . 84

- 1871 . . 1881 30. Last Fire . . . 84

- 1871 . . 1881 31. Her Gifts . . 85

- 1871 . . 1881 32. Equal Troth . . 85

- 1871 . . 1881 33. Venus Victrix . . 85

- 1871 . . 1881 34. The Dark Glass . . 86

- 1871 . . 1881 35. The Lamp's Shrine . . 86

- 1870 . . 1870 36. Life-in-love . . 86

- 1869 . . 1870 37. The Love-moon . . 87

- 1869 . . 1870 38. The Morrow's Message . 87

- 1869 . . 1869 39. Sleepless Dreams . 87

- 1871 . . 1881 40. Severed Selves . . 88

- 1871 . . 1881 41. Through Death to Love . 88

- 1871 . . 1881 42. Hope Overtaken . . 88

- 1871 . . 1881 43. Love and Hope . . 89

- 1871 . . 1881 44. Cloud and Wind . . 89

- 1869 . . 1870 45. Secret Parting . . 89

- 1869 . . 1870 46. Parted Love . . 90

- 1852 . . 1869 47. Broken Music . . 90

- 1869 . . 1870 48. Death-in-love . . 90

- 1869 . . 1869 49, 50, 51, 52. Willowwood . 91

- 1871 . . 1881 53. Without Her . . . 92

- 1871 . . 1881 54. Love's Fatality . . 92

- 1870 . . 1870 55. Stillborn Love . . 93

- 1881 . . 1881 56, 57, 58.

True Woman(Her-

self—Her Love—Her Heaven) 93 - 1871 . . 1881 59. Love's Last Gift . 94

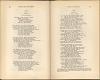

-

-

Part II.—Change

and Fate:

- 1873 . . 1881 60. Transfigured Life . . 94

- 1880 . . 1881 61. The Song-Throe . . . 95

- 1873 . . 1881 62. The Soul's Sphere . . . 95

- 1869 . . 1869 63. Inclusiveness . . . 95

- 1873 . . 1881 64. Ardour and Memory . . 96

- 1853 . . 1869 65. Known in Vain . . . 96

- 1873 . . 1881 66. The Heart of the Night . . 96

- 1854 . . 1869 67. The Landmark . . . . 97

- 1855 . . 1870 68. A Dark Day . . . . 97

- 1850 . . 1870 69. Autumn Idleness . . . 97

- 1853 . . 1870 70. The Hill Summit . . . 98

- 1848 . . 1870 71, 72, 73. The Choice . . . 98

- 1849 . . 1870 74, 75, 76.

Old and New Art

(St. Luke the Painter—Not

as These—The Husbandmen) 99 - 1867 . . 1868 77. Soul's Beauty . . . 100

- 1867 . . 1868 78. Body's Beauty . . . 100

- 1870 . . 1870 79. The Monochord . . . 101

- 1873 . . 1881 80. From Dawn to Noon . . 101

- 1873 . . 1881 81. Memorial Thresholds . . 101

- 1870 . . 1870 82. Hoarded Joy . . . . 102

- 1870 . . 1870 83. Barren Spring . . . 102

- 1869 . . 1870 84. Farewell to the Glen . . 102

- 1869 . . 1870 85. Vain Virtues . . . . 103

- 1862 . . 1863 86. Lost Days . . . . . 103

- 1870 . . 1870 87. Death's Songsters . . . 103

- 1875 . . 1881 88. Hero's Lamp . . . 104

- 1875 . . 1881 89. The Trees of the Garden . . 104

- 1847 . . 1870 90. “Retro me, Sathana!” . 104

- 1854 . . 1869 91. Lost on Both Sides . . 105

- 1869-73 . 1870-81 92, 93. The Sun's Shame . . 105

- 1881 . . 1881 94. Michelangelo's Kiss . . . 106

- 1869 . . 1869 95. The Vase of Life . . . 106

- 1873 . . 1881 96. Life the Beloved . . . 106

- 1868 . . 1869 97. A Superscription . . . 107

- 1870 . . 1870 98. He and I . . . . . 107

- 1868 . . 1869 99, 100. Newborn Death . . . 107

- 1870 . . 1870 101. The One Hope . . 108

- 1869 . . 1870 Eden Bower . . . 109

- 1869-70 . 1870 The Stream's Secret . . 114

- 1871, also

1879 . } 1881 Rose Mary . . . 119 - 1878-80 . 1881 The White Ship . . . 138

- 1881 . . 1881 The King's Tragedy . . 145

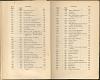

Note: The dates to the left fall under two headings: the first, “Date of Writing”, and the second, “Date of First Publication”. The numbers at right are collected in a column under the heading “Page”. -

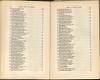

-

MISCELLANEOUS POEMS

- 1847-9 . 1850 My Sister's Sleep . . . 165

- 1847 . . 1886

For an Annunciation, Early

German . . . . 166 - 1847, etc. . 1870 Ave . . . . . 167

- 1847-70 . 1870 The Portrait . . . 169

- 1848 . . 1870

For Our Lady of the Rocks, by

Leonardo da Vinci . . 171 - 1848 . . 1886 At the Sun-rise in 1848 . . 171

- 1848 . . 1883 Autumn Song . . . . 172

- 1848 . . 1886 The Lady's Lament . . 172

- 1848 . . 1849 Mary's Girlhood . . . 173

- 1849 . . 1852 The Card-dealer . . . 174

- 1849 . . 1886 Vox Ecclesiæ, Vox Christi . 175

- 1849 . . 1870

On Refusal of Aid between

Nations . . . 175 - 1849 . . 1898 †Shakespear . . 176

- 1849 . . 1898 †Blake . . . 176

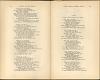

-

- 1849 . .

A Trip to Paris and

Belgium

:

- 1849 . . 1886-95 1. London to Folkestone . . 176

- 1849 . . 1886-95 2.

Boulogne to Amiens and

Paris . . . 177 - 1849 . . 1886 3.

The Staircase of Notre

Dame, Paris . . 179 - 1849 . 1881 4. Place de la Bastille, Paris 179

- 1849 . 1898 †5.

On a Handful of French

Money . . . 180 - 1849 . 1895 †6. Sonnet to the P.R.B. 180

- 1849 . . 1898 †7.

In the Train, and at Ver-

sailles . . . 180 - 1849 . 1895 †8. Last Visit to the Louvre 181

- 1849 . 1895 †9. Last Sonnets at Paris 181

- 1849 . . 1886 10.

From Paris to Brussels,

At the Paris Station . 182 - 1849 . . 1886-95 †11. On the Road . . 183

- 1849 . . 1895 †12. On the Road to Waterloo . 185

- 1849 . . 1886 13. A Half-way Pause . . 185

- 1849 . . 1895 †14. On the Field of Waterloo 185

- 1849 . . 1895 †15. Returning to Brussels . 186

- 1849 . . 1886 16. Antwerp to Ghent . . 186

- 1849 . . 1850 17. Antwerp and Bruges . . 187

- 1849 . . 1886 18. On Leaving Bruges . . 187

- 1849 . . 1898 †19. Ashore at Dover . . 188

- 1849 . . 1850

For a Venetian Pastoral, by

Giorgione . . 188 - 1849 . . 1850

For an Allegorical Dance of

Women, by Andrea Mantegna 188 - 1849 . . 1850

For “Ruggiero and

Angelica,”

by Ingres . . . 189 - 1849 . . 1850

For a Virgin and Child, by

Hans Memmelinck . . 190 - 1849 . . 1850

For a Marriage of St. Catherine,

by the Same . . . 190 - 1849 . . 1870 The Sea-limits . . . 191

- 1849 . . 1850 World's Worth . . . 191

- 1849 . . 1881 Song and Music . . . 192

- 1850 . . 1898 †Sacrament Hymn . . 192

- 1850 . . 1904 †Dennis Shand . . 193

- 1850 . . 1883 The Mirror . . . . 194

- 1850 . . 1870 A Young Fir-wood . . . 195

- 1851 . . 1886 During Music . . . . 195

- 1852 . . 1870 On the Vita Nuova of Dante . . 195

- 1852 . . 1881 Wellington's Funeral . . 196

- 1853 . . 1895 †Sonnet to Thomas Woolner . 197

- 1853 . . 1881 The Church-porches: Sonnet 1 . 198

- 1853 . . 1882 †The Church-porches: Sonnet 2 198

- 1853 . . 1870 Penumbra . . . . 198

- 1853 . . 1870 The Honeysuckle . . . 199

- 1853 . . 1881 Words on the Window-pane . 199

- 1853 . . 1871

On the Site of a Mulberry-tree;

Planted by William Shake-

spear, etc. . . 200 - 1854 . . 1870 A Match with the Moon . . 200

- 1854 . . 1863 Sudden Light . . . . 200

- 1854-69 . 1870 Stratton Water . . . 201

- 1855 . . 1870 Beauty and the Bird . . 204

- 1855 . . 1886 Dawn on the Night-journey . 205

- 1856 . . 1870 The Woodspurge . . 205

- 1859 . . 1904

†After the French Liberation

of Italy . . . 205 - 1859 . . 1870 Even So . . . 206

- 1859 . . 1870 A Little While . . . 206

- 1859 . . 1870 A New-year's Burden . . 207

- 1860 . . 1870 The Song of the Bower . . 207

- 1860 . . 1882

On Certain Elizabethan Re-

vivals . . . 208 - 1861 . . 1870 Dantis Tenebræ . . 208

- 1864 . . 1895 †The Seed of David . . 209

- 1865 . . 1870 Aspecta Medusa . . . 209

- 1865 . . 1870 Plighted Promise . . . 209

- 1867 . . 1870

The Passover in the Holy

Family . . . 210 - 1868 . . 1868 Venus Verticordia . . 210

- 1869 . . 1870 Pandora . . . 211

- 1869 . . 1881 A Sea-spell . . . 211

- 1869 . . 1870

For “The

Wine of Circe,” by

Edward Burne Jones . . 211 - 1869 . . 1870 Love-lily . . . 212

- 1869 . . 1886 English May . . . 212

- 1869 . . 1870 Cassandra . . . 213

- 1869 . . 1870

Mary Magdalene at the Door of

Simon the Pharisee . . 214 - 1869 . . 1886 Michael Scott's Wooing . . 214

- 1869 . . 1870 Troy Town . . . 214

- 1869 . . 1870 First Love Remembered . . 216

- 1869 . . 1870 An Old Song Ended . . 217

- 1871 . . 1904

†After the German Subjuga-

tion of France . . . 217 - 1871 . . 1871 Down Stream . . . . 218

- 1871 . . 1872 The Cloud Confines . . 219

- 1871 . . 1873 Sunset Wings . . . . 220

- 1871-80 . 1881 Soothsay . . . . 221

- 1873 . . 1874 Winter . . . . 223

- 1873 . . 1874 Spring . . . . 223

- 1874 . . 1874

Untimely Lost—Oliver

Madox

Brown . . . 223 - 1875 . . 1881 Parted Presence . . . 224

- 1876 . . 1881 A Death-parting . . . 225

- 1876 . . 1881 Three Shadows . . . 225

- 1876 . . 1881 Adieu . . . . 226

- 1877 . . 1881 Astarte Syriaca . . . 226

- 1878 . . 1881 Chimes . . . . 227

- 1878 . . 1881 To Philip Bourke Marston . . 228

- 1878 . . 1881 The Last Three from Trafalgar . 229

- 1879 . . 1886 Fiammetta . . . . 229

- 1880 . . 1881 Mnemosyne . . . . 229

- 1880 . . 1881 John Keats . . . . 230

- 1880 . . 1881 Thomas Chatterton . . . 230

- 1880 . . 1881 William Blake . . . 230

- 1880 . . 1881 The Day-dream . . . 231

- 1880 . . 1881 Samuel Taylor Coleridge . . 231

- 1880 . . 1881

For Spring, by

Sandro Botti-

celli . . . 232 - 1880 . . 1881

For the Holy

Family, by Michel-

angelo . . . 232 - 1881 . . 1881 Tiber, Nile, and Thames . . 233

- 1881 . . 1881 “Found” . . 233

- 1881 . . 1881 Czar Alexander the Second . 233

- 1881 . . 1881 Alas, So Long . . . 234

- 1881 . . 1881 Insomnia . . . . 234

- 1881 . . 1881 Possession . . . 235

- 1881 . . 1881 Percy Bysshe Shelley . . 235

- 1881 . . 1882 Raleigh's Cell in the Tower . 235

- 1881 . . 1881 Spheral Change . . . 236

-

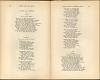

-

VERSICLES AND FRAGMENTS

- 1858 . . 1911 *God's Graal . . . 239

- 1863 . . 1886

As much as in a hundred years

she's dead . . . 239 - 1869 . . 1886 On Burns . . . . 239

- 1869 . . 1886 The Orchard-pit . . . 239

- 1870 . . 1886 To Art . . . . 240

- 1870 . . 1886 Fior di Maggio . . . 240

- 1870 . . 1886 I saw the Sybil at Cumæ . 240

- 1870 . . 1886 As balmy as the breath etc. . 240

- 1870 . . 1886 Was it a friend etc. . . 241

- 1870 . . 1886 If I could die etc. . . 241

- 1870 . . 1886 She bound her green sleeve etc. . 241

- 1870 . . 1886 Where is the man etc. . . 241

- 1871 . . 1886 At her step etc. . . . 241

- 1871 . . 1886 Would God I knew etc. . . 241

- 1871 . . 1886 I shut myself in with my soul . 241

- 1871 . . 1911 *“I hate” says over and above 241

- 1871 . . 1911

*Do still thy best, albeit the

clue . . . 241 - 1871 . . 1911 *The bitter stage of life . 242

- 1873 . . 1911

*The winter garden-beds all

bare . . . . 242 - 1875 . . 1886 Who shall say etc. . . 242

- 1875 . . 1911 *Who knoweth not etc. . . 242

- 1875 . . 1911 *Where poets all . . 242

- 1875 . . 1911 *A Bad Omen . . . 242

- 1875 . . 1911 *Even as the dreariest swamps . 242

- 1875 . . 1911 *Or reading in some sunny nook . 242

- 1875 . . 1911 *Aye, we'll all shake hands etc. . 242

- 1875 . . 1911 *And heavenly things etc. . . 242

- 1875 . . 1911 *Though all the rest go by . . 242

- 1875 . . 1911 *What face but thine etc. . . 242

- 1875 . . 1911 *With furnaces . . . . 243

- 1875 . . 1911 *And love and faith etc. . . 243

- 1875 . . 1911 *For this can love etc. . . . 243

- 1875 . . 1911 *The forehead veiled etc. . . 243

- 1875 . . 1911

*Thou that beyond thy real

self etc. . . 243 - 1875 . . 1911 *And plaintive days etc. . 243

- 1875 . . 1911 *To know for certain etc. . 243

- 1875 . . 1911 *Think through the silence etc. 243

- 1875 . . 1911 *An ant-sting's prickly at first 243

- 1875 . . 1911 *And mad revulsion etc. . 243

- 1875 . . 1911

*His face, in Fortune's favours

sunn'd . . . 243 - 1875 . . 1911 *The glass stands empty etc. . 243

- 1875 . . 1911 *O thou whose name etc. . 243

- 1875 . . 1911 *I saw the love etc. . . 243

- 1875 . . 1911 *Or give ten years etc. . 244

- 1875 . . 1911 *And the cup of human agony . 244

- 1875 . . 1911 *Even as the moon etc. . 244

- 1875 . . 1911

*The Imperial Cloak—Paluda-

mentum . . . . 244 - 1875 . . 1911 *My Lady . . . 244

- 1875 . . 1911 *Last Love . . . 244

- 1879 . . 1911 *For the garlands of heaven etc. 244

- 1879 . . 1911

*The wounded hart and the

dying swan . . . 244 - 1879 . . 1911 *Within those eyes etc. . . 245

- 1879 . . 1911 *Ah if you had been lost etc. . 245

- 1879 . . 1911 *On the two bridal-biers . . 245

- 1879 . . 1911

*Fashioned with intricate in-

finity . . . 245 - 1879 . . 1911

*Ah dear one, we were young

so long . . . 245 - 1879 . . 1911 *Joan of Arc . . . . 245

- 1879 . . 1911

*The tombless fossil of deep-

buried days . . . 245 - 1879 . . 1911

*And 'mid the budding branches'

sway . . . 245 - 1879 . . 1911 *In galliard gardens etc. . 245

- 1879 . . 1911

*When we are senseless

grown

etc. . . . 245 - 1879 . . 1911

*Or, stamped with the snake's

coil, it be . . . 245 - 1879 . . 1911 *Could Keats but have etc. . 246

- 1880 . . 1911 *Dîs Manibus . . . . 246

- 1880 . . 1911 *Ah lads, I knew your father . . 246

- 1880 . . 1911 *This little day etc. . . 246

- 1880 . . 1911 *No ship came near etc. . 246

- 1880 . . 1911 *And plaintive days etc. . 246

- 1880 . . 1911 *Inexplicable blight . . 246

Sig. c -

-

FOREIGN (WITH

SOME ENGLISH

- 1849 . . 1852 Motto to the Card Dealer . 249

- 1867 . . 1903 †Messer Dante a Messer Bruno 249

- 1867 . . 1886 Con manto d'oro etc. . . 249

- 1867 . . 1886 With golden mantle etc. . 249

- 1867 . . 1886 Robe d'Or . . . 249

- 1867 . . 1886 A golden robe etc. . . . 249

- 1868 . . 1911

*For a Portrait of Mrs. William

Morris . . . 250 - 1869 . . 1886 Thomæ Fides . . . 250

- 1871 . . 1881 Gioventù e signorìa . 250

- 1871 . . 1881 Youth and Lordship . . . 251

- 1872 . . 1881 Proserpina . . . . 252

- 1872 . . 1881 Proserpina . . . . 253

- 1875 . . 1875 La Bella Mano . . . 253

- 1875 . . 1875 La Bella Mano . . . 253

- 1875 . . 1886 Barcarola . . . 254

- 1875 . . 1886 Barcarola . . . 254

- 1875 . . 1886 Bambino Fasciato . . . 254

- 1875 . . 1911 *Et les larmes etc. . . 254

- 1875 . . 1911 *Pro hoste hostem etc. . . 254

- 1875 . . 1911

*Il faut que tu le tiennes

pour dit . . . 255 - 1878 . . 1911 *Del mare il susurro sonoro . 255

- 1880 . . 1886 La Ricordanza . . . 255

- 1880 . . 1886 Memory . . . . 255

TRANSLATIONS) -

-

JUVENILIA AND GROTESQUES

- 1847 . . 1911 *Algernon Stanhope . . . 259

- 1847 . . 1911 *Epitaph for Keats . . . 260

- 1847 . . 1911 *To Mary in Summer . . . 260

- 1848 . . 1898 †The English Revolution of 1848 261

- 1848 . . 1906

†The Sin of

Detection—Bouts-

rimés . . 263 - 1848 . . 1911 *Afterwards, Bouts-rimés . 263

- 1848 . . 1911

*One of Timé's Riddles,

Bouts-

rimés . . . 263 - 1848 . . 1898 †Another Love, Bouts-rimés . 264

- 1848 . . 1898

†The World's Doing,

Bouts-

rimés . . . 264 - 1848 . . 1911 *Almost Over, Bouts-rimés 264

- 1848 . . 1911 *Hidden Harmony, Bouts-rimés 265

- 1848 . . 1911 *An Altar-flame, Bouts-rimés . 265

- 1848 . . 1911 *Height in Depth, Bouts-rimés 265

- 1848 . . 1911 *At Issue, Bouts-rimés . 266

- 1848 . . 1911 *Praise and Prayer, Bouts-rimés 266

- 1848 . . 1911 *The Turning-point, Bouts-rimés 266

- 1848 . . 1911 *A Foretaste, Bouts-rimés 267

- 1848 . . 1911 *Idle Blessedness, Bouts-rimes 267

- 1848 . . 1895 †'Twas thus . . . 267

- 1848 . . 1911 *A Prayer . . . . 267

- 1849 . . 1911 *On Browning's Sordello . . 268

- 1849 . . 1895 †The Can-can at Valentino's . 268

- 1849 . . 1898

†At the Station of the Ver-

sailles Railway . . 269 - 1849 . . 1895 †L'Envoi, Brussels . . 269

- 1849 . . 1898 †Sir Peter Paul Rubens . . 269

- 1849 . . 1900 †Between Ghent and Bruges . 270

- 1850 . . 1900 †Verses to John L. Tupper . 270

- 1851 . . 1895 †St. Wagnes' Eve . . 271

- 1852 . . 1898 †“Uncle Ned”—Parody 271

- 1853 . . 1892 †Duns Scotus . . . 271

- 1853 . . 1895 †MacCracken . . . 272

- 1855 . . 1899 †Valentine to Lizzie Siddal . 272

- 1857 . . 1892 †Dalziel Brothers . . 273

- 1869 . . 1892 †The Wombat . . . 273

- 1869-71 . 1903-11 †Limericks . . . . 273

- 1871 . . 1892 †On William Morris . 276

- 1871 . . 1911 *The Brothers . . . . 276

- 1871 . . 1911 *Smithereens . . . 277

- 1878 . . 1908 †On Christina Rossetti . 277

-

-

TRANSLATIONS

- 1845-9, etc. 1861

Dante and his Circle, with the

Italian Poets preceding him . 281

[ For List of Contents and Index of First Lines, see pp. 285-95.] - 1844 . . 1900 †Lenore, translated from Bürger 501

- 1846 . . 1886

Henry the Leper, from

Hart-

mann von Auë . . . 507 - 1847 . . 1886

Two Songs, from Victor Hugo's

“Burgraves” . . 533 - 1848 . . 1886

Capitolo: A. M. Salvini to Fran-

cesco Ridi, 16— . . 533 - 1848 . . 1874

Two Lyrics from Niccolò Tom-

maseo (The Young Girl—A

Farewell) . . . . 535, 536 - 1849 . . 1911

*In Absence from Becchina—

from Cecco Angliolieri . . 536 - 1850 . . 1911

*Lines from the Roman de la

Rose . . . 537 - 1853 . . 1853

Poems by Francesco and Gaetano

Polidori . . . 537 - 1866 . . 1911 *A Doctor's Advice . . . 541

- 1866 . . 1911 *My Lady . . . 541

- 1866 . . 1886 Lilith—From Göthe . . 541

- 1869 . . 1869

The Ballad of Dead Ladies—

Francois Villon, 1450 . . 541 - 1869 . . 1869

To Death, of his

Lady—François

Villon . . . 542 - 1869 . . 1870 John of Tours—Old French . 542

- 1869 . . 1870 My Father's Close—Old French 543

- 1869 . . 1870

Beauty—A Combination from

Sappho . . . 544 - 1869 . . 1881 The Leaf—from Leopardi . 544

- 1870 . . 1870

His Mother's Service to our

Lady—Villon . . . 544 - 1878 . . 1879 Francesca da Rimini—Dante . 545

- 1880 . . 1886 La Pia—Dante . . . . 546

- 1845-9, etc. 1861

Dante and his Circle, with the

-

-

PROSE

- 1849 . . 1850 Hand and Soul . . . 549

- 1850 . . 1886 St. Agnes of Intercession . 557

- 1850 . . 1850

Exhibition of Modern British

Art at the Old Water-colour

Gallery, 1850 . . 570 - 1850 . . 1850 Frank Stone: Sympathy, 1850 . 572

- 1850 . . 1850

J. C. Hook: The

Departure of

the Chevalier Bayard from

Brescia, 1850 . . 572 - 1850 . . 1850

Anthony: The Rival's

Wed-

ding, 1850 . . . . 572 - 1850 . . 1850 Branwhite . . . . . 573

- 1850 . . 1850 Lucy . . . . . . 573

- 1850 . . 1850 F. R. Pickersgill . . . . 574

- 1850 . . 1850 C. H. Lear . . . . 574

- 1850 . . 1850 Kennedy . . . . . 575

- 1850 . . 1850 Cope . . . . . 575

- 1850 . . 1850 Landseer . . . . 576

- 1850 . . 1850 Marochetti . . . . 577

- 1851 . . 1851

The Modern Pictures of all

Countries, at Lichfield House 577 - 1851 . . 1851

Exhibition of Sketches and

Drawings in Pall Mall East 581 - 1851 . . 1851 Madox Brown . . . . 583

- 1851 . . 1851 Poole . . . . 585

- 1851 . . 1851 Holman Hunt . . . . 585

- 1851 . . 1898 Deuced Odd . . . . 586

- 1858 . . 1911 *Lancelot and Guenevere . . 587

- 1862-80 . 1863-80 William Blake . . . 587

- 1864 . . 1903 †The Seed of David . . . 605

- 1866 . . 1903

Scraps: Essays Written in the

Intervals of Lock-jaw, etc. . 605 - 1866 . . 1866

The Return of Tibullus to

Delia . . . 605 - 1866-78 . 1866 Sentences and Notes . . 606

- 1869 . . 1911 *A Ground-Swell . . . 607

- 1869 . . . 1886 The Orchard Pit . . . 607

- 1869 . . 1886 The Doom of the Sirens . . 610

- 1870 . . . 1911 *Walter H. Deverell, a Raffle . 613

- 1870 . . . 1911 *Silence, for a Design . . . 613

- 1870 . . . 1870 Ebenezer Jones . . . 613

- 1870 . . . 1886 Subjects for Pictures . . . 614

- 1870 . . . 1886 The Cup of Water . . . 615

- 1870 . . . 1886 Michael Scott's Wooing . . . 616

- 1870 . . . 1886 The Palimpsest . . . 616

- 1870 . . . 1886 The Philtre . . . 617

- 1870 . . . 1871

The Stealthy School of Criti-

cism . . . . 617 - 1870 . . . 1871

Hake's Madeline, and Other

Poems . . . 621 - 1870 . . . 1871 Maclise's Character-Portraits . 627

- 1873 . . . 1873 Hake's Parables and Tales . . 630

- 1874 . . . 1911 *Proserpina . . . 635

- 1874 . . . 1911 *Scraps, The Press-gang, etc. . 635

- 1875-81 . . 1886 Samuel Palmer, 1875-81 . . 637

- 1878 . . . 1911

*Scraps: There are certain

passionate phrases, etc. . 637 - 1878 . . . 1911

*Notes upon a Life of David

Scott . . . 638 - 1880 . . . 1911

*Scraps: Round Tower at Jhansi

etc. . 642 - 1881 . . . 1911

*Note on Rossetti's Boyish

Ballad, Sir Hugh the Heron 643 - 1881 . . . 1881 †Dante's Dream . . 643

- NOTES by Wm. M. Rossetti . . . . . 647

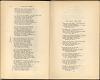

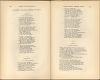

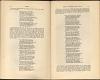

- The blessed damozel leaned out

- From the gold bar of Heaven;

- Her eyes were deeper than the depth

- Of waters stilled at even;

- She had three lilies in her hand,

- And the stars in her hair were seven.

- Her robe, ungirt from clasp to hem,

- No wrought flowers did adorn,

- But a white rose of Mary's gift,

- 10 For service meetly worn;

- Her hair that lay along her back

- Was yellow like ripe corn.

- Herseemed she scarce had been a day

- One of God's choristers;

- The wonder was not yet quite gone

- From that still look of hers;

- Albeit, to them she left, her day

- Had counted as ten years.

- (To one, it is ten years of years.

- 20 . . . Yet now, and in this place,

- Surely she leaned o'er me—her hair

- Fell all about my face. . .

- Nothing: the autumn-fall of leaves.

- The whole year sets apace.)

- It was the rampart of God's house

- That she was standing on;

- By God built over the sheer depth

- The which is Space begun;

- So high, that looking downward thence

- 30 She scarce could see the sun.

- It lies in Heaven, across the flood

- Of ether, as a bridge.

- Beneath, the tides of day and night

- With flame and darkness ridge

- The void, as low as where this earth

- Spins like a fretful midge.

- Around her, lovers, newly met

- 'Mid deathless love's acclaims,

- Spoke evermore among themselves

- 40 Their heart-remembered names;

- And the souls mounting up to God

- Went by her like thin flames.

- And still she bowed herself and stooped

- Out of the circling charm;

- Until her bosom must have made

- The bar she leaned on warm,

- And the lilies lay as if asleep

- Along her bended arm.

- From the fixed place of Heaven she saw

- 50 Time like a pulse shake fierce

- Through all the worlds. Her gaze still strove

- Within the gulf to pierce

- Its path; and now she spoke as when

- The stars sang in their spheres.

- The sun was gone now; the curled moon

- Was like a little feather

- Fluttering far down the gulf; and now

- She spoke through the still weather.

- Her voice was like the voice of the stars

- 60 Had when they sang together.

- (Ah sweet! Even now, in that bird's song,

- Strove not her accents there,

- Fain to be hearkened? When those bells

- Possessed the mid-day air,

- Strove not her steps to reach my side

- Down all the echoing stair?)

- “I wish that he were come to me,

- For he will come,” she said.

- “Have I not prayed in Heaven?—on earth,

- 70 Lord, Lord, has he not pray'd?

- Are not two prayers a perfect strength?

- And shall I feel afraid?

- “When round his head the aureole clings,

- And he is clothed in white,

- I'll take his hand and go with him

- To the deep wells of light;

- As unto a stream we will step down,

- And bathe there in God's sight.

- “We two will stand beside that shrine,

- 80 Occult, withheld, untrod,

- Whose lamps are stirred continually

- With prayer sent up to God;

- And see our old prayers, granted, melt

- Each like a little cloud.

- “We two will lie i' the shadow of

- That living mystic tree

- Within whose secret growth the Dove

- Is sometimes felt to be,

- While every leaf that His plumes touch

- 90 Saith His Name audibly.

- “And I myself will teach to him,

- I myself, lying so,

- The songs I sing here; which his voice

- Shall pause in, hushed and slow,

- And find some knowledge at each pause,

- Or some new thing to know.”

- (Alas! We two, we two, thou say'st!

- Yea, one wast thou with me

- That once of old. But shall God lift

- 100 To endless unity

- The soul whose likeness with thy soul

- Was but its love for thee?)

- “We two,” she said, “will seek the groves

- Where the lady Mary is,

- With her five handmaidens, whose names

- Are five sweet symphonies,

- Cecily, Gertrude, Magdalen,

- Margaret and Rosalys.

- “Circlewise sit they, with bound locks

- 110 And foreheads garlanded;

- Into the fine cloth white like flame

- Weaving the golden thread,

- To fashion the birth-robes for them

- Who are just born, being dead.

- “He shall fear, haply, and be dumb:

- Then will I lay my cheek

- To his, and tell about our love,

- Not once abashed or weak:

- And the dear Mother will approve

- 120 My pride, and let me speak.

- “Herself shall bring us, hand in hand,

- To Him round whom all souls

- Kneel, the clear-ranged unnumbered heads

- Bowed with their aureoles:

- And angels meeting us shall sing

- To their citherns and citoles.

- “There will I ask of Christ the Lord

- Thus much for him and me:—

- Only to live as once on earth

- 130 With Love,—only to be,

- As then awhile, for ever now

- Together, I and he.”

- She gazed and listened and then said,

- Less sad of speech than mild,—

- “All this is when he comes.” She ceased.

- The light thrilled towards her, fill'd

- With angels in strong level flight.

- Her eyes prayed, and she smil'd.

- (I saw her smile.) But soon their path

- 140 Was vague in distant spheres:

- And then she cast her arms along

- The golden barriers,

- And laid her face between her hands,

- And wept. (I heard her tears.)

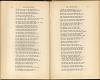

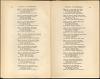

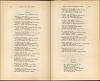

- Yea, thou shalt learn how salt his food who fares

- Upon another's bread,—how steep his path

- Who treadeth up and down another's stairs.

- Behold, even I, even I am Beatrice.

- Of Florence and of Beatrice

- Servant and singer from of old,

- O'er Dante's heart in youth had toll'd

- The knell that gave his Lady peace;

- And now in manhood flew the dart

- Wherewith his City pierced his heart.

- Yet if his Lady's home above

- Was Heaven, on earth she filled his soul;

- And if his City held control

- 10 To cast the body forth to rove,

- The soul could soar from earth's vain throng,

- And Heaven and Hell fulfil the song.

- Follow his feet's appointed way;—

- But little light we find that clears

- The darkness of the exiled years.

- Follow his spirit's journey:—nay,

- What fires are blent, what winds are blown

- On paths his feet may tread alone?

- Yet of the twofold life he led

- 20 In chainless thought and fettered will

- Some glimpses reach us,—somewhat still

- Of the steep stairs and bitter bread,—

- Of the soul's quest whose stern avow

- For years had made him haggard now.

- Alas! the Sacred Song whereto

- Both heaven and earth had set their hand

- Not only at Fame's gate did stand

- Knocking to claim the passage through,

- But toiled to ope that heavier door

- 30 Which Florence shut for evermore.

- Shall not his birth's baptismal Town

- One last high presage yet fulfil,

- And at that font in Florence still

- His forehead take the laurel-crown?

- O God! or shall dead souls deny

- The undying soul its prophecy?

- Aye, 'tis their hour. Not yet forgot

- The bitter words he spoke that day

- When for some great charge far away

- 40 Her rulers his acceptance sought.

- “And if I go, who stays?”—so rose

- His scorn:—“and if I stay, who goes?”

- “Lo! thou art gone now, and we stay”

- (The curled lips mutter): “and no star

- Is from thy mortal path so far

- As streets where childhood knew the way.

- To Heaven and Hell thy feet may win,

- But thine own house they come not in.”

- Therefore, the loftier rose the song

- 50 To touch the secret things of God,

- The deeper pierced the hate that trod

- On base men's track who wrought the wrong;

- Till the soul's effluence came to be

- Its own exceeding agony.

- Arriving only to depart,

- From court to court, from land to land,

- Like flame within the naked hand

- His body bore his burning heart

- That still on Florence strove to bring

- 60 God's fire for a burnt offering.

- Even such was Dante's mood, when now,

- Mocked for long years with Fortune's sport,

- He dwelt at yet another court,

- There where Verona's knee did bow

- And her voice hailed with all acclaim

- Can Grande della Scala's name.

- As that lord's kingly guest awhile

- His life we follow; through the days

- Which walked in exile's barren ways,—

- 70 The nights which still beneath one smile

- Heard through all spheres one song increase,—

- “Even I, even I am Beatrice.”

- At Can La Scala's court, no doubt,

- Due reverence did his steps attend;

- The ushers on his path would bend

- At ingoing as at going out;

- The penmen waited on his call

- At council-board, the grooms in hall.

- And pages hushed their laughter down,

- 80 And gay squires stilled the merry stir,

- When he passed up the dais-chamber

- With set brows lordlier than a frown;

- And tire-maids hidden among these

- Drew close their loosened bodices.

- Perhaps the priests, (exact to span

- All God's circumference,) if at whiles

- They found him wandering in their aisles,

- Grudged ghostly greeting to the man

- By whom, though not of ghostly guild,

- 90 With Heaven and Hell men's hearts were fill'd.

- And the court-poets (he, forsooth,

- A whole world's poet strayed to court!)

- Had for his scorn their hate's retort.

- He'd meet them flushed with easy youth,

- Hot on their errands. Like noon-flies

- They vexed him in the ears and eyes.

- But at this court, peace still must wrench

- Her chaplet from the teeth of war:

- By day they held high watch afar,

- 100 At night they cried across the trench;

- And still, in Dante's path, the fierce

- Gaunt soldiers wrangled o'er their spears.

- But vain seemed all the strength to him,

- As golden convoys sunk at sea

- Whose wealth might root out penury:

- Because it was not, limb with limb,

- Knit like his heart-strings round the wall

- Of Florence, that ill pride might fall.

- Yet in the tiltyard, when the dust

- 110 Cleared from the sundered press of knights

- Ere yet again it swoops and smites,

- He almost deemed his longing must

- Find force to yield that multitude

- And hurl that strength the way he would.

- How should he move them,—fame and gain

- On all hands calling them at strife?

- He still might find but his one life

- To give, by Florence counted vain;

- One heart the false hearts made her doubt,

- 120 One voice she heard once and cast out.

- Oh! if his Florence could but come,

- A lily-sceptred damsel fair,

- As her own Giotto painted her

- On many shields and gates at home,—

- A lady crowned, at a soft pace

- Riding the lists round to the dais:

- Till where Can Grande rules the lists,

- As young as Truth, as calm as Force,

- She draws her rein now, while her horse

- 130 Bows at the turn of the white wrists;

- And when each knight within his stall

- Gives ear, she speaks and tells them all:

- All the foul tale,—truth sworn untrue

- And falsehood's triumph. All the tale?

- Great God! and must she not prevail

- To fire them ere they heard it through,—

- And hand achieve ere heart could rest

- That high adventure of her quest?

- How would his Florence lead them forth,

- 140 Her bridle ringing as she went;

- And at the last within her tent,

- 'Neath golden lilies worship-worth,

- How queenly would she bend the while

- And thank the victors with her smile!

- Also her lips should turn his way

- And murmur: “O thou tried and true,

- With whom I wept the long years through!

- What shall it profit if I say,

- Thee I remember? Nay, through thee

- 150 All ages shall remember me.”

- Peace, Dante, peace! The task is long,

- The time wears short to compass it.

- Within thine heart such hopes may flit

- And find a voice in deathless song:

- But lo! as children of man's earth,

- Those hopes are dead before their birth.

- Fame tells us that Verona's court

- Was a fair place. The feet might still

- Wander for ever at their will

- 160 In many ways of sweet resort;

- And still in many a heart around

- The Poet's name due honour found.

- Watch we his steps. He comes upon

- The women at their palm-playing.

- The conduits round the gardens sing

- And meet in scoops of milk-white stone,

- Where wearied damsels rest and hold

- Their hands in the wet spurt of gold.

- One of whom, knowing well that he,

- 170 By some found stern, was mild with them,

- Would run and pluck his garment's hem,

- Saying, “Messer Dante, pardon me,”—

- Praying that they might hear the song

- Which first of all he made, when young.

- “Donne che avete”* . . . Thereunto

- Thus would he murmur, having first

- Drawn near the fountain, while she nurs'd

- His hand against her side: a few

- Sweet words, and scarcely those, half said:

- 180 Then turned, and changed, and bowed his head.

- For then the voice said in his heart,

- “Even I, even I am Beatrice”;

- And his whole life would yearn to cease:

- Till having reached his room, apart

- Beyond vast lengths of palace-floor,

- He drew the arras round his door.

* Donne che avete intelletto d'amore:—the first canzone of the Vita Nuova.

- At such times, Dante, thou hast set

- Thy forehead to the painted pane

- Full oft, I know; and if the rain

- 190 Smote it outside, her fingers met

- Thy brow; and if the sun fell there,

- Her breath was on thy face and hair.

- Then, weeping, I think certainly

- Thou hast beheld, past sight of eyne,—

- Within another room of thine

- Where now thy body may not be

- But where in thought thou still remain'st,—

- A window often wept against:

- The window thou, a youth, hast sought,

- 200 Flushed in the limpid eventime,

- Ending with daylight the day's rhyme

- Of her; where oftenwhiles her thought

- Held thee—the lamp untrimmed to write—

- In joy through the blue lapse of night.

- At Can La Scala's court, no doubt,

- Guests seldom wept. It was brave sport,

- No doubt, at Can La Scala's Court,

- Within the palace and without;

- Where music, set to madrigals,

- 210 Loitered all day through groves and halls.

- Because Can Grande of his life

- Had not had six-and-twenty years

- As yet. And when the chroniclers

- Tell you of that Vicenza strife

- And of strifes elsewhere,—you must not

- Conceive for church-sooth he had got

- Just nothing in his wits but war:

- Though doubtless 'twas the young man's joy

- (Grown with his growth from a mere boy,)

- 220To mark his “Viva Cane!” scare

- The foe's shut front, till it would reel

- All blind with shaken points of steel.

- But there were places—held too sweet

- For eyes that had not the due veil

- Of lashes and clear lids—as well

- In favour as his saddle-seat:

- Breath of low speech he scorned not there

- Nor light cool fingers in his hair.

- Yet if the child whom the sire's plan

- 230 Made free of a deep treasure-chest

- Scoffed it with ill-conditioned jest,—

- We may be sure too that the man

- Was not mere thews, nor all content

- With lewdness swathed in sentiment.

- So you may read and marvel not

- That such a man as Dante—one

- Who, while Can Grande's deeds were done,

- Had drawn his robe round him and thought—

- Now at the same guest-table far'd

- 240 Where keen Uguccio wiped his beard.*

* Uguccione della Faggiuola, Dante's former protector, was now his fellow-guest at Verona.

- Through leaves and trellis-work the sun

- Left the wine cool within the glass,—

- They feasting where no sun could pass:

- And when the women, all as one,